Aleksandr Zhitomirsky

Humanism + Dynamite = The Soviet Photomontages of Aleksandr Zhitomirsky

Through January 10, 2017

Photography Galleries 1-4

The Art Institute of Chicago

111 S Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois, 60603

Having endured one of the most polarizing and vitriolic Presidential elections this country has seen in recent history, the current exhibition, Humanism + Dynamite = The Soviet Photomontages of Aleksandr Zhitomirsky, at the Art Institute of Chicago appears to have landed at the most opportune time. In over 100 works (book maquettes, printed ephemera, and photomontages) spanning a large swath of the 20th century, political and corporate corruption, the liberation of Africa and Asia, racial division in the west, and the international oil crises and rise of dictatorships in the 1970s-1980s are presented by master photo-monteur (photography-engineer), satirist, and loyal Soviet citizen, Aleksandr Zhitomirsky.

Alexandr Zhitomirsky. It’s Time to Shoot Yourself, Herr Göring!, 1941.

Ne boltai! Collection. © Vladimir Zhitomirsky.

Little known outside of Russia, Aleksandr Zhitomirsky (1907–1993) was born in Rostov-on-Don, (a provincial town near the southeastern Ukranian border). In his youth, he studied locally with Aleksandr Silin, then moved to Moscow to earn a diploma in Drawing at the Central Studio of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia under the guidance of Ilya Mashkov, followed by studies in the studio of Vladimir Favorsky. Working in all aspects of the graphic arts (magazine production to illustration), Zhitomirsky contributed to numerous publications, including Frontovaia illiustratsiia (Front Illustrated), Sovetskii Soiuz (Soviet Union), Pravda (Truth), Izvestiia (News), and Ogonek (Spark). Combining a socialist philosophy with the appropriation of recognized images, Zhitomirsky produced seminal political photomontages that criticized the Nazi regime, the western politics of the Cold War, and the widespread economic and social injustices occurring during his lifetime around the world. The materials presented span more than five decades, nearly the entire Soviet era.

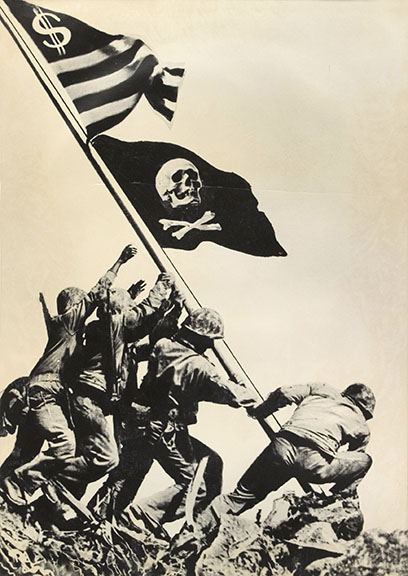

Aleksandr Zhitomirsky. The Monument in Honor of the U.S. Marines in

Washington . . . , 1984. Ne boltai! Collection. © Vladimir Zhitomirsky.

Influenced by German communist artist John Heartfield, Zhitomirsky came to prominence through his creation of leaflets and magazines that were dropped by planes on German troops as part of the psychological propaganda machine employed as part of the Soviet air campaign. Vladimir Zhitomirsky, Aleksandr’s son, notes in the preface of the accompanying exhibition monograph that his father’s photomontages were not directed against the German soldier, but the fascist demagoguery being exploited by the Nazi regime. Exact numbers are not known, but it is thought that Zhitomirsky’s leaflets contributed to thousands of German soldiers deployed on the Eastern Front surrendering in the latter stages of the 2nd World War. His poignant photomontages even allegedly earned him a place on the “most wanted list” of Soviet propagandists by Joseph Goebbel, Reich Minster of Propaganda. And, supposedly, Zhitomirsky was ordered to be executed on sight.

Aleksandr Zhitomirsky. Soldiers Fall—Profits Rise . . ., 1967. Ne boltai! Collection. © Vladimir Zhitomirsky.

Over-the-top propaganda is a powerful tool in swaying the masses. Here, in the states, the Left, the Right, and those in-between can certainly attest to the power of the appropriated image combined with severe political message. By-in-large, most will not question the presented material due to the labor involved. Zhitomirsky understood the nature of his audience and the potential of combining iconic imagery with political outcry to advance his cause. In The Art of Political Photomontage, 1983, Zhitomirsky summarizes his philosophy for assembling and directing interpretation of content.

“What gives the strength of dynamite to the photo-poster and pamphlet? First of all, its motto is humanism. And, of course, the ability to see in subjects something new, that which others do not see, but that they should by all means see.”

There is sublime clarity in Zhitomirsky. His ability to shift interpretation in even the most iconic of nationalist imagery sets a precedent that we (America) have unknowingly embraced. Whether we like it or not, in our digital age, all voices are now seen as equal, regardless of empirical evidence. This acceptance appears to have become commonplace and the uncertainty attached to this mode of collective reponse is not far from what was encountered in Asia and Europe during the first half of the 20th century.

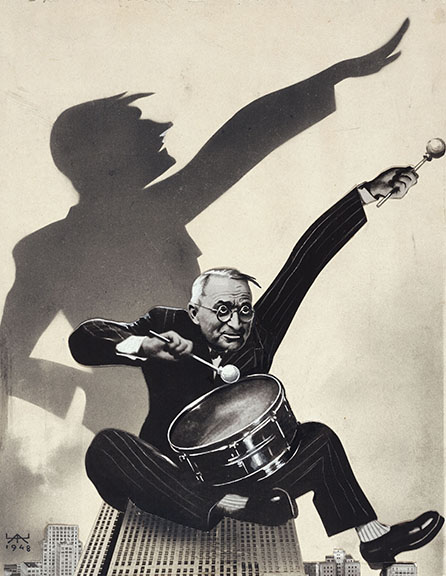

Aleksandr Zhitomirsky. Harry Truman: The Hysterical War Drummer, 1948.

Ne boltai! Collection. © Vladimir Zhitomirsky.

Political propaganda is rooted in direct divisive design. The intent is to incite response, therefore supporting the producer’s stance. Throughout the exhibit, one will encounter uncomfortable imagery that will require the viewer to take time to contemplate the message, artist, and period in which the work was created. In Harry Truman: The Hysterical War Drummer, 1948, the 33rd president of the United States actively beats a snare drum with what appears to be a saluting silhouette of Adolph Hitler in background. This trite tactic is nothing different from the propaganda encountered in our recent political elections. Cliché becomes powerful through accepting the message. At best, the viewer will hopefully hold the ability to question the artwork’s intent, realize the historical tensions that prevailed in post-WW II politics, and find amusement in the absurdity.

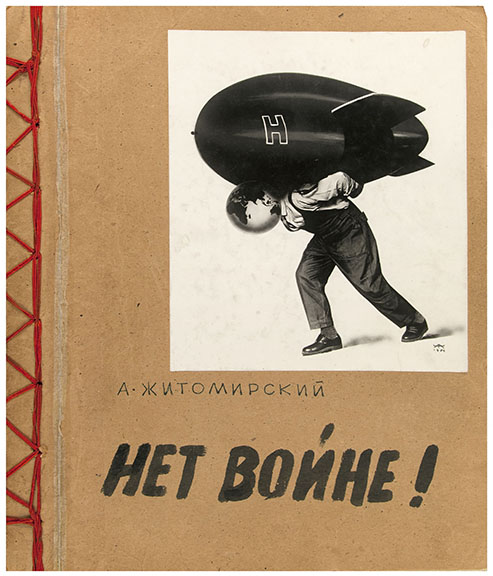

Aleksandr Zhitomirsky. No to War! maquette, about 1963.

Ne boltai! Collection. © Vladimir Zhitomirsky.

The day after the recent election I revisited the work of Zhitomirsky once again. I was attempting to understand the obvious schism dividing our country. Oddly, I wanted to locate a sense of unity through viewing materials antithetical to America. I posed questions to myself: Where does our division reside? How different are our needs across the country? How did we get to this place? Are we heading toward civil unrest or peaceful response? For a moment, I felt an unfelt sadness not encountered in some time. I continued to tour the exhibit and noted the similarities and differences in our present day to that of the climate and times that Zhitomirsky produced these powerful images. I came to a crossroads, and realized that this is exactly where we reside today. America is at a point where a paradigm shift is in process, the uncertainty encountered a century ago in Asia and Europe is now centralized here. Our responsibility is to illustrate our country’s compassion and ability to work together. The world is watching, and our collective response will impact humanity around the globe for the next 100 years.

Additional images from: Humanism + Dynamite = The Soviet Photomontages of Aleksandr Zhitomirsky

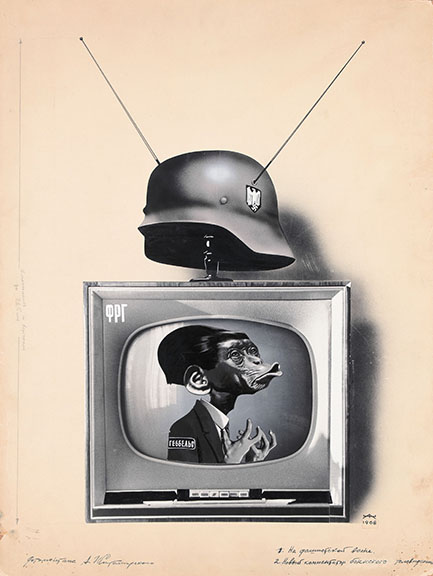

Aleksandr Zhitomirsky. On the Military Wavelength, 1968.

Ne boltai! Collection. © Vladimir Zhitomirsky.

Aleksandr Zhitomirsky. The Voice of America, 1950. Ne boltai! Collection. © Vladimir Zhitomirsky.

For additional information, please visit:

The Art Institute of Chicago – Humanism + Dynamite = The Soviet Photomontages of Aleksandr Zhitomirsky

Review by Chester Alamo-Costello