Currently, Jeff Carter, along with Susan Giles and Faheem Majeed, is presenting works in Tuned Mass at the Chicago Cultural Center through January 6, 2019. Carter’s aesthetic practice merges his interest in early 20th c. Modernism with ideas that address our mass consumer culture, polarizing political commentary, and a technical acumen for producing finely tuned sculptural and sonic works that are often specific to the site exhibited. This week the COMP Magazine visited Carter to discuss his early interests in photography and how it laid the foundation for current works, his modifying of IKEA materials, the intersection of ideas and process in his sculpture, and contemporary practices of protest.

Jeff Carter, FAKTURA: A, modified IKEA products (steel, laminated MDF, polypropylene, nylon, hardware), transducers, amplifiers, MP3 players, 2-channel audio composition, 60” H x 72” W x 22” D, 2015

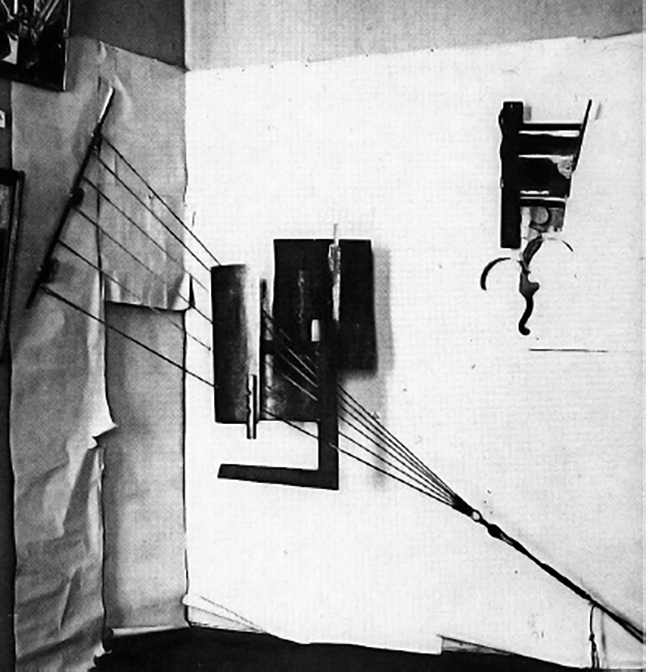

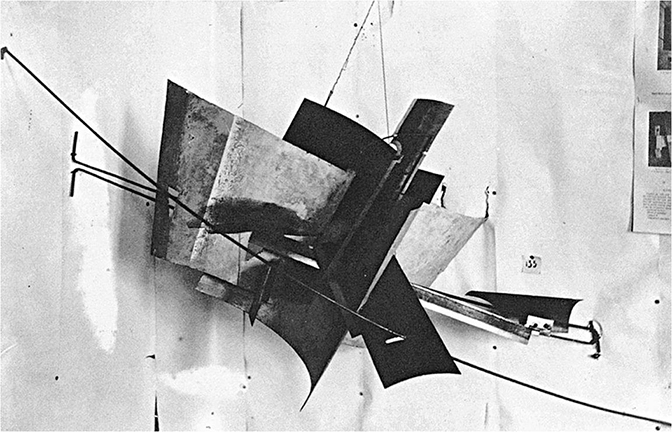

Vladimir Tatlin, Counter-Courner Relief 1914-15 – Iron, copper, wood, cables. Dimensions unknown, no longer extant.

I’m curious about foundations and trajectory. You grew up out west in Colorado, and have lived and worked in Chicago for a number of years. In much of your practice, architecture and space are merged with new technology. Can we start with any early experiences or memories that set you on your path in terms of your present day aesthetic investigations?

When I was a kid, my mom took a photography course and then turned my bathroom into a darkroom (it was the only room in the house with no windows), and so photography as a process was very familiar to me. My first art classes in college at CU Boulder were in photography. I eventually became more interested in making sculpture, but the ideas of photography probably shaped by conceptual trajectory the most.

Jeff Carter, FAKTURA: B, modified IKEA products (steel, galvanized steel, laminated MDF, wood, LEDs, electronics, hardware), programmed microcontroller,

52” H x 54” W x 30” D, 2015

Vladimir Tatlin, Counter-Courner Relief 1915 Aluminum, tin, wood, oil paint, wire Dimensions unknown, no longer extant

Can we discuss the intersection of ideas and process in your sculptural practice? You identify object and memory as being a central platform in your practice since 1994. I’m wandering how your approach to these items has evolved? How do you see new media impacting your approach? What specific tenets do you see continually resurfacing?

I think my early interest in darkroom photography is where the emphasis on both process and memory in my work comes from. Much of my earliest sculpture was about photography or specific half-forgotten photographs. After grad school, my work on tourism was also focused on the fragmented relationship between image, object/souvenir, and memory. My more recent projects continue to expand on these themes – for example, the FAKTURA project was developed from a handful of photographs depicting Vladimir Tatlin’s long-lost (and presumed destroyed) proto-Constructivist Corner-Counter Reliefs from 1914-15.

Protest has been another regular area of investigation. In 2017, you produced occupier_castle, a site-specific multi-channel audio installation at Newtown Castle, Burren College of Art, CO. Clare, Ireland. Can you discuss this opportunity? Also, can you offer insight to sound element, “castle_except”, in terms of selecting the musical score and samples taken from protests around the world?

The opportunity to do a project at the Burren College of Art resulted from a short summer residency that Susy (Giles) and I had there the previous summer. Like most people, I was fascinated by the 16th century castle on the campus and thought it would make a great site for a sound installation, so I did some preliminary studies, developed the project and was invited back to install it. The castle’s roof had been restored – it is an enormous wooden cone made of Irish oak. I thought that I could turn it into a loudspeaker by attaching transducers to the beams, and the sound would resonate throughout the castle. So one of the soundtracks is a harpist playing scales, and I mixed this into a “Shepard scale” to create the audio illusion of tones continual ascending or descending. Protest itself is a relatively new subject in my work, and this project was the first to incorporate aspects of it.

Jeff Carter, occupier_castle, site-specific multi-channel audio installation at Newtown Castle, Burren College of Art, Co. Clare, Ireland, amplifiers, transducers, sensors, WAV triggers, Arduino microcontrollers, hardware, 2017

Jeff Carter, occupier_castle, site-specific multi-channel audio installation at Newtown Castle, Burren College of Art, Co. Clare, Ireland, amplifiers, transducers, sensors, WAV triggers, Arduino microcontrollers, hardware, 2017

Jeff Carter, occupier_castle, site-specific multi-channel audio installation at Newtown Castle, Burren College of Art, Co. Clare, Ireland, amplifiers, transducers, sensors, WAV triggers, Arduino microcontrollers, hardware, 2017

You have been working with IKEA products for a number of years. In this you essentially are “hacking” IKEA products (tables, bookshelves, and flooring), to produce new sculptural works. What prompted this use of materials? Can you walk us through the conceptual and tactile process?

I first used IKEA materials because they were cheap – I found some laminated panels of MDF for one dollar apiece in the “scratch and dent” section of the store and used them to make The Surface, an installation of geometric replicas of rocks on the surface of Mars as seen in photographs send back from the Pathfinder spacecraft (hey, more photography!). I noticed that when I mentioned that the material came from IKEA, people seemed interested. So I began to try to extract more direct content from that material by exploring the history of IKEA and it’s relationship to early 20th-century architecture and industrial design. This has led to several projects with a focus on the Bauhaus and Constructivism, and follows two main themes: the sociopolitical underpinnings of Modernist philosophy, and the technical innovations that inform Modernist aesthetics. Filtering these references through the IKEA catalog by hacking their products has kept me very engaged and full of ideas. On a technical level, these materials are very difficult to work with. I approach them as if they were “raw” materials, but in fact they are highly refined products that predetermine how we build and use them. So my process is more of a negotiation.

Jeff Carter, Occupier_1, modified IKEA products (wood, umbrellas, LEDs, glassware, electric drill),

60″ H x 96″ W x 48″ D, 2016

Jeff Carter, Occupier_1 (detail), modified IKEA products (wood, umbrellas, LEDs, glassware, electric drill),

60″ H x 96″ W x 48″ D, 2016

Jeff Carter, Occupier_1 (detail), modified IKEA products (wood, umbrellas, LEDs, glassware, electric drill),

60″ H x 96″ W x 48″ D, 2016

At present you are producing a solo exhibit, Occupier, for the Chicago Cultural Center. In one work, you have created a large protest barricade with kinetic and sound elements. Where does this effort reside in terms of your present investigations that look at the relationship between the Modern avant-garde and contemporary consumer design culture?

The current project is starting to explore some new territory, in that there are no explicit references to iconic Modern forms or particular art historical movements. Prompted by seeing images of incredible bamboo barricades built in Hong Kong during the 2014 pro-democracy protests, I began thinking about vernacular constructions – in this case, what has been described as an “architecture of dissent”. Barricades built by protestors are meant to visibly occupy public space, to inhibit the movement of authorities, and to protect protestors. As architectural constructions they are immediate reflections of location, circumstance, and labor. So as much as they are hyperlocalized, IKEA designs are global, and this contrast led me to the idea of “formalizing” the protest barricades. These new pieces reference familiar domestic interiors and the functionality of furniture, yet also express the raw utility and aggressive form of street barricades, thereby conflating the space of the spectator with that of the activist.

Jeff Carter, occupier_4, Tuned Mass, Chicago Cultural Center, 2018

Photograph courtesy of James Prinz Photography.

What do you value most in your sculpture practice?

The opportunity to be inventive, solve problems and conduct research is what I value most about my practice. I also think that the physical activity involved in making my sculpture is very satisfying.

Jeff Carter, sculptor, Chicago, 2018

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Jeff Carter, please visit:

Jeff Carter – http://jeff-carter.net/html/

Chicago Cultural Center – https://www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/dca/supp_info/tuned_mass.html

Art in America – https://www.artinamericamagazine.com/reviews/jeff-carter/

Artadia – https://artadia.org/artist/jeff-carter/

The Mission – https://themissionprojects.com/news/item74/Jeff-Carter-Art-Ltd-Magazine

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello