In examining historical narrative paintings, Persian culture, and her personal life experience, Iranian artist Orkideh Torabi crafts fascinating sardonic tales that comment on our male dominated world. Recently, Torabi presented a series of these works at the Weinberg/Newton Gallery in River North. This week the COMP Magazine headed up to Torabi’s studio in Logan Square to discuss her recent exhibition, her youth in Tehran, Iran, her investigation of societal constructs as applied to her paintings, and her fascination with the Chicago Imagists.

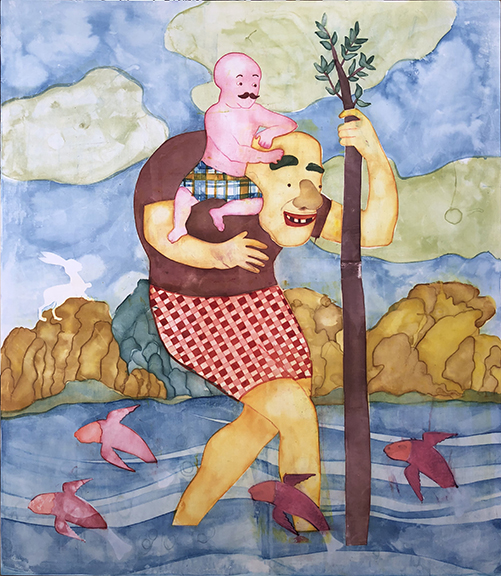

Orkideh Torabi, “Sit tight”, 43X37 inches, fabric dye on stretched cotton, 2018

I’m wondering if we can begin with a little background? You grew up in Iran, studied graphic design, then came to the realization that you wanted more control over what you created. You then shifted your attention to painting and eventually landed in Chicago to study at UIC. What prompted this shift in your aesthetic focus? Why did you see this change as instrumental in defining your voice?

I have long had a specific interest in the life of females and their position within male-dominated societies. My experience is drawn from a larger aspect of daily life. Growing up, I gradually recognized how women do not benefit from the same opportunities as men in their everyday lives. Having consistently observed how many facets of society are established to favor men over women, I questioned how my life may differ if none of these boundaries existed. When people become more aware of their surroundings, they develop the ability to critical explore the norms that have emerged. I wanted to draw attention to these issues through my artwork. Within the art I have the same ability as males in these so-called structures to be on the same platform. I have the capacity to share ideas without feeling limited. Since moving to the United States, I’ve met people from different backgrounds who share similar insights and personal struggles. I wanted to depict all of these aspects in my work and, through doing so, painting became a valuable outlet through which I could express myself free from the confines of social structures.

Orkideh Torabi, “Daddy’s boy” 43X37 inches, fabric dye on stretched cotton, 2016

In conversation you noted an interest in the Chicago Imagists. There are evident parallels in your technical approach to that seen in the artwork of Gladys Nilsson. This is evident in the line-work, application of pigment, and attention to the figure. However, your investigations focus upon very different themes (e.g., patriarchy and cultural constructs) that are specific to your life experience. What do you find intriguing with the Imagists? Do you see any overlap in what you are producing to that of these Chicago artists?

There have definitely been some overlaps between Chicago Imagists and my own work, and their art has influenced my work; however, there is no direct correlation. I wasn’t aware of the Imagists until I moved to Chicago and became acquainted with their work. I’ve always been interested in satirical cartoons and the way they can address serious topics through the lens of humor. I recognized this quality in the work of the Imagists, and I was drawn to it. I like the way the Imagists comment on civil rights, feminism, and war through satire. I think irony and humor are becoming more universal and accessible to people of a variety of backgrounds.

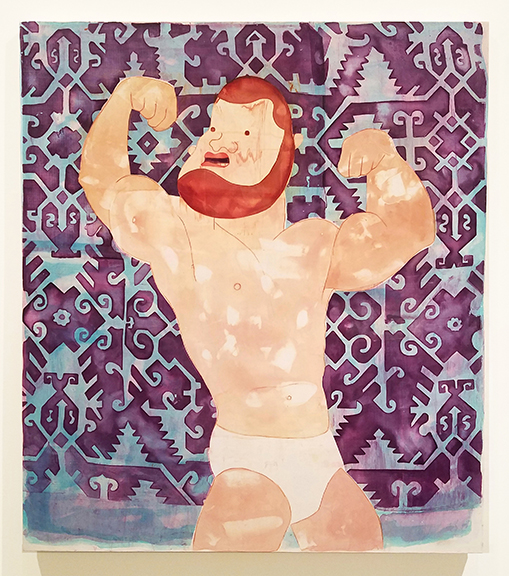

Orkideh Torabi, “Chubby mubby”, 43X37 inches, fabric dye on stretched cotton, 2018

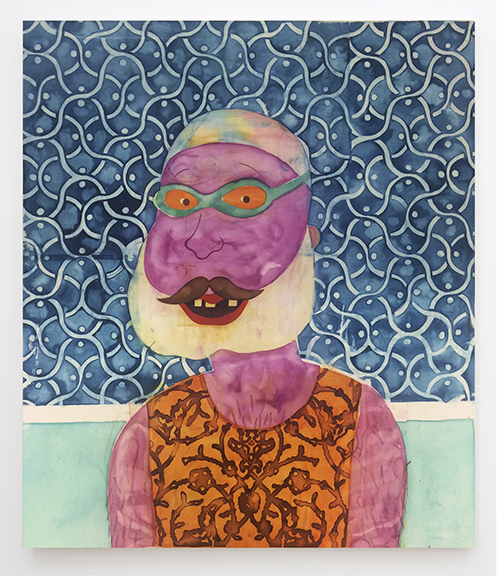

I see a fairly unique convergence of visual strategies that are specific to Chicago and that seen in the use of pattern in the arts of the Middle East surfacing in your recent works. Specifically, in Daddy’s Cotton Candy and Chubby Mubby (2018). How do you see your applied practice merging your contrasting life experience?

For me, the use of pattern comes from the inspiration I have gleaned from Persian miniatures and manuscripts. In addition, growing up, I was significantly influenced by the old buildings and mosques decorated with beautiful tiles that are a standard element of the landscape. Several years ago, I researched Persian manuscript and lithographed books for a project and was really impressed by the images; in fact, they had a huge impact on me. I developed a deeper understanding of these images and a new-found appreciation for them. As a result, they began to appear in my paintings in the forms of symbolic shapes and lines. Every element of the image in Persian miniatures are decorated with very beautiful patterns. In fact, putting these patterns alongside images of contemporary men serves to remind the viewer of our relationship with the past. I use these patterns to merge the past with the present.

Orkideh Torabi, installation view at Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, IL, 2016

Societal constructs that emphasize male-dominated hierarchies is an area your aesthetic investigations comment upon. You’ve even gone as far as removing women from your paintings. In our present-day milieu, we are experiencing a rise in visibility of female artists. What do you hope to contribute to this changing perspective?

I used to raise these issues through painting women; however, I began shifting my focus to a more indirect representation of social constructs and, instead, started to use images of males juxtaposed with images from art history to get my point across.

Many topics are worthy of discussion, and there is an inherent need for artists to raise awareness of the issues that plague women. Such awareness can only be raised by discussing the problems that exist within the context of the structures that have been established to justify accepted norms. We all recognize these issues, but few people truly pay attention to them. As a female artist, I am trying to highlight the realities of contemporary society through my paintings.

Alison Ruttan, Deborah Stratman, and Orkideh Torabi, installation view of Weight of a World

at Weinberg/Newton Gallery, Chicago, IL, 2018

Orkideh Torabi, installation view of Weight of a World

at Weinberg/Newton Gallery, Chicago, IL, 2018

You currently had work on view in the exhibition Weight of the World at the Weinberg/Newton Gallery in River North through September 15th. Your efforts are contrasted with that of Alison Ruttan and Deborah Stratman. Can you walk us through your process for preparing for and realizing this presentation?

Revisiting history has been a major focus of my recent body of works. My art is narrative based, and the stories I tell are typically derived from something I have read or experienced. Sometimes, I look at historical art images for inspiration and reference. The works I study can range from Persian miniatures to historic western paintings; it doesn’t matter.

For example, the “Madonna” series was inspired by an article I read about countries in which men favor sons over daughters because sons carry their lineage. I was reminded of this article when I encountered an image of the Madonna and child, and it immediately struck me as the ideal place from which I could explore the concepts that interest me. I wanted to develop my own version of this iconic image and, thereby, give it a new life in the contemporary era. As such, every painting in this series is based on a story.

Also, the main room of the gallery is covered with wallpaper that is adorned with Persian patterns. This space is, in fact, these men’s territory. This is a space where males feel comfortable because no women are present. The wallpapers act glue that holds the men together and sustains their power and masculinity.

Orkideh Torabi, installation view of Horton Gallery/Western Exhibitions,

NADA Art Fair, New York, NY, 2018

What do you value most in your aesthetic practice?

It’s hard to answer this question because everything in the image is important to me. I think all elements of the painting work in collaboration to promote the harmony of the overall aesthetic. No single aspect would be successful in isolation. The elements of the art that I value most can also vary according to the piece I am working on. Sometimes, the texture and color of the painting become very important because these aspects are the most intuitive elements of my paintings.

Orkideh Torabi, “Where are all the houries?”, 37X43 inches, fabric dye on stretched cotton, 2018

With the exhibition, Weight of the World set, what are you currently working upon? Do you have any specific plans for the remainder of 2018? What do you hope to realize by year’s end?

I would probably go to my home country to visit my family and stay there for a few months. Also, I am planning to travel to different cities in Iran to do some research. Iran is a great place for me to get inspiration and ideas for the new body of works. I have two solo shows in 2019. I’m already getting ready for them.

Orkideh Torabi, “I’ll catch you” 43X37 inches, fabric dye on stretched cotton, 2017

For additional information on the painting practice of Orkideh Torabi, please visit:

Orkideh Torabi – http://www.orkidehtorabi.com/

Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts – http://www.bemiscenter.org/residency/by_year/2017/orkideh-torabi.html

Lenny Letter – https://www.lennyletter.com/story/how-iranian-painter-orkideh-torabi-found-her-voice

The Visualist – http://www.thevisualist.org/2018/09/artist-walk-through-with-alison-ruttan-and-orkideh-torabi/

Weinberg/Newton Gallery – http://weinbergnewtongallery.com/conversations/artist-interview-orkideh-torabi-44/

Western Exhibitions – http://westernexhibitions.com/artist/orkideh-torabi/

Orkideh Torabi, painter, Chicago, 2018

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello