One of the traits that sticks out when I think about the studio practice of Tim Lowly is the idea of perseverance. This is a key staple that can be seen in many aspects of his life and practice. From the long standing devotion to his daughter (Temma) to his sustained teaching career at North Park University to his process in creating highly realistic drawings and paintings, there’s a sense of purpose that has been acquired through consistently facing stiff challenges. This week the COMP Magazine jumped on Metra’s Milwaukee District West line and headed out to Elk Grove Village to discuss with Lowly his youth spent in South Korea, the significant role Temma has played in his studio practice, the role collaboration has played in his art making process, and what he is currently working upon.

Can we start with discussing your youth. You were born in Hendersonville, North Carolina. Your parents were medical missionaries and you spent most of your youth in South Korea. I’m curious if you see any connections with this experience and your chosen path in being an artist?

My parents chose a life of service as missionaries: When we moved to South Korea in 1961 the country was still recovering from the Korean War. And there was poverty everywhere. My father had business experience that led to him becoming a hospital administrator in Jeonju. My mother taught piano and organ and puppetry in a women’s college. The example of their lives was obvious: be authentically present and do something meaningful with your life. Early on I became enamored with art making, and that led me to be an Art major in college. Shortly after my partner Sherrie and I were married in 1981 we went to Korea to teach English for a year. That time was very meaningful in several ways, but a particularly important development for me was meeting the Korean artist Lim Ok Sang. Lim was a key member of the Minjung Art movement which at it’s core was concerned with making art that in some capacity gave agency to the poor and other marginalized members of society (the Minjung) and which critiqued societal structures of power and inequity.

Another key formative event for me at that time was after that year in Korea Sherrie and I travelled through Europe for six weeks, including three weeks with my parents. For me the contact with art of the Renaissance and Baroque period was definitive in shaping my desire to make art that was deeply invested in representation at the highest level I could muster. By comparison (with the art we were seeing on that trip) much of the contemporary art work I had seen to that point seemed caught up in aesthetic experimentation and decoration.

You have been making serious work for over 40 years. Between 1994 and 2023 you were a professor, artist-in-residence and ran the North Park University Gallery in Chicago. Simply put, aesthetic investigations have been central in your being. Can you describe this fascination and why it has been a mainstay for such a long period of time?

As noted already I latched on to art making as a vocation fairly early on. A key development occurred in the early ‘80s when I was invited to be one of five artists in residence at the Urban Institute for Contemporary Art in Grand Rapids, Michigan. One of the responsibilities of that group of artists in residence was that we were also the exhibition committee tasked with choosing the artists to show (from a multitude of submissions) and installing the exhibitions. Years later that experience of art gallery management led to my being hired to run the gallery at North Park University in Chicago. My exhibition record and other experiences subsequently helped open the door to teaching at NPU. And over time my position at NPU grew to a fairly ideal Artist-in-Residence / Professor / Gallery Director position which lasted over twenty years. I recently retired from NPU. Being able to combine teaching, curating and art making led to a kind diversification that ultimately was very enabling for me. But I am quite happy to be able to focus more specifically on my art practice now.

Temma, your daughter, is severely disabled with cerebral palsy with spastic quadriplegia. She has been the primary subject in much of your drawings and paintings. In simplest terms, can you describe why you feel so strongly about making her the key protagonist in your art practice?

Early in Temma’s life I painted her on occasion, but as she became an adult it felt increasingly important to represent her more emphatically as a way of giving a kind of representative presence for a population that is largely institutionalized and absent in society at large. I’ve employed different strategies in this enterprise, including a series of large scale paintings of her and another of paintings of her that meaningfully reference various Renaissance and Baroque paintings.

Making art of someone who is profoundly disabled and who is not able to give or refuse consent to being represented (artistically or otherwise) is an ethically problematic enterprise and generally prohibited. The problem with that general prohibition is that this meaningful population is inadequately represented or known. With that in mind on a few occasions during my years of teaching drawing I would bring Temma to school and invite students to draw her At one point one of the students (a little older than the other students and who worked at an institution caring for profoundly disabled individuals) pulled me aside and demanded an explanation of why it was acceptable for the students to be drawing Temma. I was frankly taken aback and embarrassed that I had failed to explain my rationale for this practice. I went on to explain that while there is ethical justification for preventing such a practice that it was no less important to affirm the right of someone such as Temma to be represented in a way that honors their being, meaningfulness and dignity.

Can we discuss your process? I am curious how you see your ideas germinating, then being transformed into the tactile artwork. Do you see your process as embedded in planning, intuition, or a combination?

It is a bit of an exaggeration, but generally I feel like I’m starting from scratch. Every time. Much of my work is based on my own photography. Over the years I’ve taken thousands of photographs, some with intentions towards paintings or drawings and others that I later choose as a reference for a painting. In terms of ideas, I usually have some sort of conceptual armature that I’m working with. Some examples: 1) With the Rainbow Girl project I am making paintings of Temma, each of which alludes in some way (including the title) to a specific painting of the Renaissance and Baroque periods of art. 2) With the Radiator project I am also painting Temma with each painting (from my perspective) referencing Temma’s mystical, unexpected, metaphorical, and even actual “agency”. 3) With my current Voice & Site project I am making drawings: each of a person in a place, reflecting on their being, vocation and mystery.

My process involves multiple aspects: intuition, research, planning, history + thought + medium + making + presenting / exhibiting .

It feels that your 2013 publication “Trying to Get a Sense of Scale” offers a clear overview up to that year of your work focused upon Temma, your wife, and your life experience. Can you describe what you hoped to present in this publication that coincided with an exhibition at Visual Arts Center at the Washington Pavilion, Sioux Falls, South Dakota?

The essays in that book are intended the reader more of an understanding of what was behind–or what my intentions were with–the artworks. There were multiple pieces and types of writing all of which–like the reproduced art–circled around the same subject: Temma. Someone might “read” this practice as an obsession, but–while I do love making art representing Temma–the decision to produce so much art related to her is related to the relative lack of representation of people like her.

What do you value most in your aesthetic investigations and studio practice?

Art making, music making, teaching have all contributed to a sense of purposefulness. Life is definitely fleeting and undoubtably my creative practice carries the desire to make something that is in some measure lasting and meaningful.

Assistance with the production of this painting by Maggie Hubbard.

What are you currently working upon? What is the plan for the remainder of the year? Do you have any upcoming exhibitions or other items we should look out for?

I feel fortunate to have had several wonderful exhibition opportunities in the last year and another one is coming up next Spring at Aurora University. One of my primary goals for the next while is to secure gallery representation in Chicago.

Two of my current / on-going projects–the Rainbow Girl Project and the Radiator Project–are related to my daughter Temma. To be clear: I have no intent to sentimentalize or idealize Temma. My hope is that in suggesting various ways I find her life to be meaningful there might be a broadened possibility of consideration for others who are culturally, politically and socially marginalized.

In the Rainbow Girl Project I am making paintings of Temma which are in conversation with fairly well known paintings of the Renaissance and Baroque period.

Representative examples of the Rainbow Girl Project:

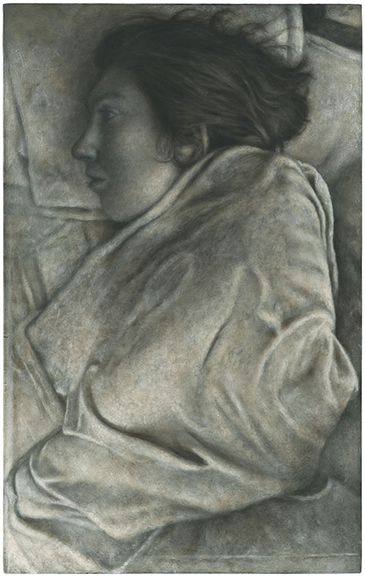

Coroação, acrylic on panel, 10″ x 14” – The title of this painting Coroação means “Coronation” in Portuguese. While the word might be used in reference to any coronation (such as that of a king) it’s most common usage seems to be in reference to the coronation of Mary (the mother of Jesus). In this regard the painting references a relatively unknown, but wonderful painting: Coroação da Virgem, by Domingos Antonio de Sequeira: in particular the rainbow in that painting that “crowns” the occasion. A step further: the title alludes to the popular Coroação de Nossa Senhora ceremony: an event that seems to celebrate the participating girls’ innocence: connecting them–in that regard–to Mary. While Temma is quite different than Mary, she does seem to move through life in a state of perpetual innocence.

“La Bergère d’Arcadie” (“The Shepherdess of Arcadia”), 2016, acrylic on panel, 24″x 15” – This painting references Poussin’s painting “Et in Arcadia Ego” (“I am also in paradise”) and in Poussin’s painting it is engraved on a tomb that Arcadian shepherds are pondering. The implication is that death (the “I”) is present in paradise. The day after Temma (my daughter: the subject of much of my work) was born she stopped breathing and had a cardiac arrest. It seems accurate to say that she has spent much of her life on that edge and has a kind of understanding of death that most of us don’t. Further, despite many physical problems that most of us would find intolerable she seems to be quite at peace much of the time.

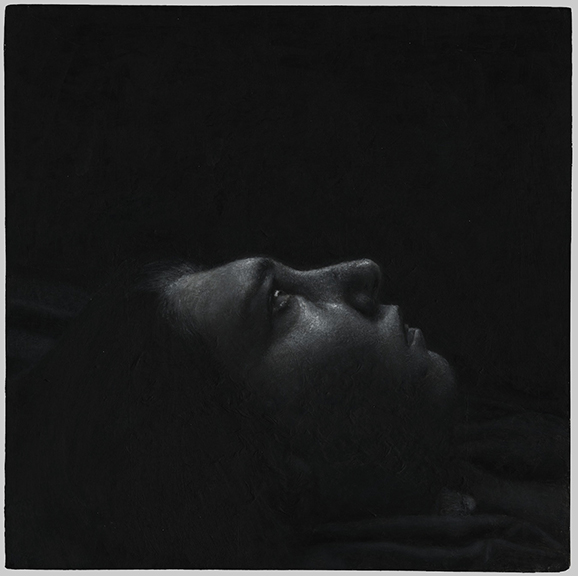

“Oculus: Di sotto in sù”, 2022, acrylic on panel, 18″ x 18” – One of the most famous works of the early Renaissance is Andrea Mantegna’s Camera degli Sposi (“Chamber of the Bride and the Groom”). The title is a bit misleading in that the room’s walls and ceiling are covered with highly realistic “trompe l’oil” painting which celebrate the social and political importance of the Duke Ludovico III whose residence the room is in. Somewhat ironically the most commonly noted portion of the painting of this room is the “Oculus” (Latin for “eye”) on the ceiling: seemingly a circular opening to the sky. Around the edges of this opening are a peacock, eight putti (baby angels) and five women who most likely would not have been privy to the political occasions depicted on the walls below. They seem to be laughing at the scene below. The inclusion of this relatively marginal group (both in terms of the political power and spatial location) seems to subtly mock the occasions of power depicted below. My “all things Italian” friend Steven Carrelli suggested including the art historical term “Di sotto in sù” (“as seen from below”) as a way of subtly emphasizing that political implication. In my painting the “sky” depicted in Mantegna’s Oculus is loosely quoted, but the only person present is Temma, looking down at us over the edge, perhaps–in her rather enigmatic way similarly–raising questions of power and significance.

The Radiator Project proposes understanding Temma (and others like her) as having unexpected kinds of agency.

On the morning of April 10, 2018, after tending to my daughter Temma and while standing by her bed, the word “Radiator” came to mind. I liked the word in relation to my experience of Temma who–like a radiator–is relatively static in her presence and yet radiates a kind meaningfulness that belies that stasis. I took a series of photograph of Temma there as she lay in bed: starting the photographing at one end and moving parallel to the bed. Those images–all seeing from straight ahead–were then assembled to create an image that complicates and supersedes our experience of seeing from one place at one time (since one is seeing everything in the resulting image as if from eight different locations at the same time–all straight in front). I did this photographing process a number of times over the following weeks until the version that I ended up using for the painting came along. On that day at the end of that particular photographing session it occurred to me to take the braid (beautiful as it was!) out of Temma’s hair and that tumbling torrent of her hair said “now!”. So it began.

The other paintings in the Radiator project were based on photoworks I had taken previously, each of which suggested (at least to me) some way in which Temma has a kind of (perhaps mystical) agency. The titles are intended to suggest that agency with a single word beginning with R–the latter “limitation” perhaps mirroring the apparently obvious limitation of this profoundly disabled thirty-eight year old woman.

Representative examples of the Radiator project:

“Radiator”, 2018, 48″ x 117″, acrylic on panel

Assistance with the production of this painting by Maggie Hubbard.

“Revelator”, 2018, acrylic on panel, 13″ x 10”. Private collection.

“Receptor”, 2018, acrylic on panel, 17″ x 17″. Private collection.

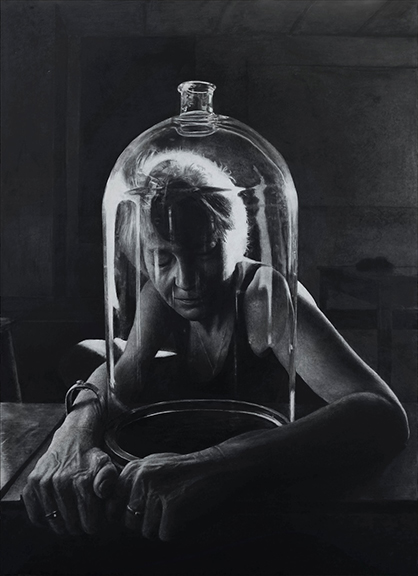

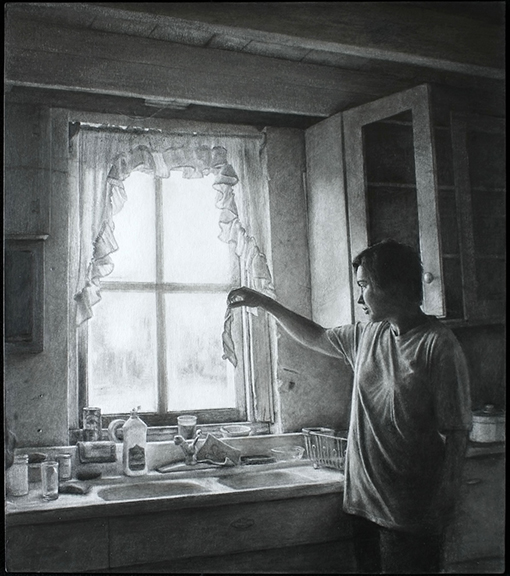

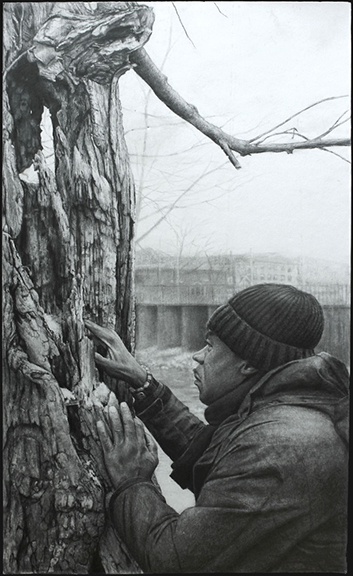

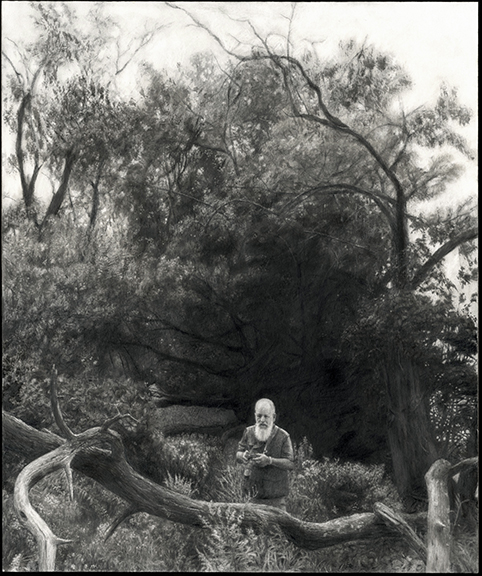

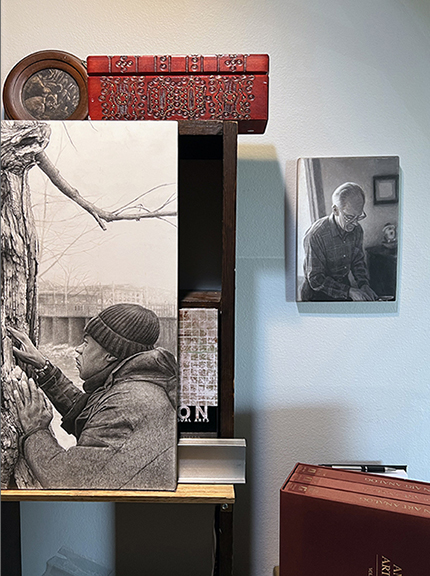

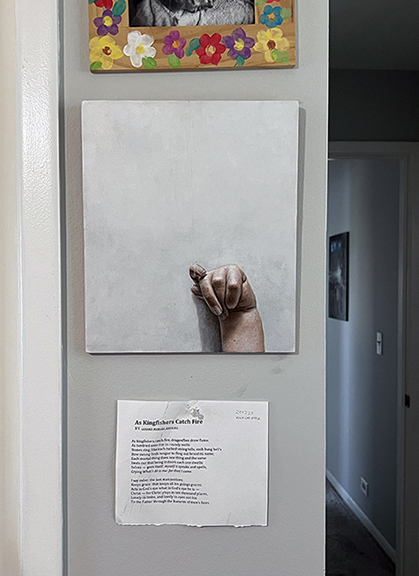

Voice & Site Project. Ever since I began art making professionally in the early 1980s I’ve had a practice of making artworks which reflect on an individual in a place, their being and vocation. The Voice & Site project is the most recent iteration of this long time practice, with a focus on drawing. Rather labor intensive drawings. Here are four examples:

“Jar : Riva Lehrer”, 2022, graphite and ink on drawing board, 28.5” x 40”.

“The Perspective : Greg Metzler”, 2022, graphite and ink on drawing board, 16.25″ x 19.5”

“Leaf in Light : Katie Schofield”, 2024, graphite and ink on drawing board, 19” x 16.5”

“Tender : Tony Zamblé”, 2024, graphite and ink on drawing board, 19.3″ x 11.7″

For additional information on the studio practice of Tim Lowly, please visit:

Tim Lowly – https://timothylowly.com

Tim Lowly on Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/timlowly/

Tim Lowly on Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/tlowly/

Tim Lowly on Flickr – https://www.flickr.com/photos/timlowly/

Minneapolis Institute of Art Collection – https://collections.artsmia.org/art/125394/at-25-tim-lowly

Realism Today – https://realismtoday.com/acrylic-portraits-painting-my-daughter-temma/

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello