In his fascination with non-traditional materials, the intersection of American and Middle-Eastern fables, and a willingness to upend long-standing histories, Ali Seradge offers a fresh look at how one interprets past narratives while being firmly placed in the present. On one level, Seradge’s creations are clearly jolie laide, even cause for inciteful response, yet Seradge extends this definition through offering a perspective that reflects his family’s Iranian heritage coupled with an upbringing in the American west. This week, the COMP Magazine visited Seradge at his East Garfield Park studio to discuss the foundations for his practice, selection of materials, ongoing inquiry and reinterpretations of myth, and how all of these items assemble into his painting practice.

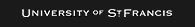

Ali Seradge, Xeno Semihundido, oil painting on upholstery, 24″x30″, 2018

You grew up in Oklahoma City and studied painting at SAIC and out in Baltimore at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). However, you had another life prior to focusing on painting. What made you shift your focus to the visual arts? Do you see any overlap in your approach to painting and your studies and work in the psychology field?

Hahaha! yeah. I wanted to be a comic book artist by the end of high school, but like a lot of kids, especially with immigrant parents, art is not presented as a viable profession. So, I went Biochem/Pre-Med, then to Psych. I went to medical school, and in those times everyone is working super hard towards their goal. It was in that environment I decided that I needed to make a switch. It took me a year to fully realize that I definitely wanted to be an artist.

I do think my years studying Psychology influence my understanding of art, but not in any pop-culture-mind-hunter kind of way. Good psychology is data driven and has tons of confounding and contextual factors that are always being adjusted for and analyzed, including our own physiology and anatomy. Artists who are concerned with their audiences’ read or reaction to the work have to consider similar factors.

Art and psychology also have relations to the physicality of the human body. Structures in the brain act with the rest of the body to create behavior. Similarly, you can’t talk about the experience of color without addressing the phenomenology of visible light as well as our physiological reaction to that phenomenon. Our history has missteps in both fields, I think Kandinsky’s ideas on color theory are analogous to phrenology’s contributions to the study of the mind.

So those kinds of thoughts bounce around my head while I am making a work. I think the best way to sum it up is with the idea of test design. Designing tests is an enormous area in psychology. You have to have generate and test certain behaviors in the audience. How you phrase the questions, layout, modality, and feedback are all factors. That doesn’t even include cultural and environmental concerns. Finally, you have to honestly evaluate and be open to the criticism of your audience and your peers so you can improve.

For me specifically, add the consideration of putting the human/ humanoid figure into the mix. I absolutely consider human pattern recognition, proprioception, “like me” bias, and other reactions that are unique to humans perceiving human animal forms. These considerations are often why I use human analogues or surrogates in my paintings. It is the same psychology behind science fiction stories like District 9, their humanoid form allows the viewer to map their own physical experience in the poses they see in the painting the same way we read the stances and gestures of other people around us.

Ali Seradge, Edith of the Ogallala, oil on suede houndstooth, 12″ x 12″, 2018

You are fascinated by myth. Your family moved to the U.S. from Iran prior to your birth. And, you often refer to stories that are distinct to the Middle East. I’m interested in your approach and application in translating these stories into a contemporary format. What piqued your interest in this content? Can you discuss your process of selection? What do you hope to convey in this effort?

I would say fascinated, critical, and optimistic. It started as a search for my own personal history, that’s why they started in the Middle East. As I learned the history of the region and how it relates to my current home, my focus stayed there. Myths are fascinating because they give insight into the virtues and values of people in that specific place and time. We should be critical because those values often don’t translate to our current situation. Scheherazade marries the mass rapist and murder that held her and her sister hostage for about 3 years, that’s not a fucking lesson for today. But! I’m optimistic because we are the editors of our own culture, artists especially.

As a cultural producer and editor, I think it is important to adjust our myths so that they still help and provide guidance to their audience. So I select the ones where that incongruity between past and current ideals are greatest. This goes for the story as well as the conventions of it’s visual representation.

First we should want people to think critically about the stories they receive. Next, I want the myths I choose to relay information that is helpful to my audience now. There is this idea that myths and religious texts are unchanged, but we know otherwise. They are constantly being edited, sometimes organically or by committee. When you understand that, you have a powerful tool at your disposal.

Ali Seradge, Scylla and Charbidis, oil painting on car upholstery, 11″x11″ , 2018

You regularly paint upon nontraditional materials (designer fabric, foam). I assume you are on a first name basis with the staff at Textile Discount Outlet down on 21st street in Pilsen. Why did you select to paint upon this type of material? What technical obstacles do you encounter? Is there a specific conceptual element that you see in working with these types of materials?

Lol. Not on a first name basis yet! but soon! That store is awesome!

Technical Obstacles? Oh man. Aside from the peanut gallery screaming how un-archival everything this, the porous surfaces gobble up oil paint. The oil slides and takes holidays on the smooth surfaces. Some of the fabrics are thick and springy, so they resist being folded and stretched. I must be a masochist, lol.

There are three reasons for the material choice, and each presents a different conceptual attack. First, is because painting has been around a lot longer that cotton duck, which only become the support of choice in 16th century Italy and spread from there. This ties into using foam to create irregular surfaces. With that, I am embracing this leviathan of an unprivileged history of painting on what you could, or on objects you made or surfaces you found. Second is the idea of flesh and skin. Oil paint is more durable and flexible than watercolor or tempera, so if you were decorating leather or hide for the outside world, that would be your choice. Which brings me to the last reason: Failure. I don’t paint on actual leather, I paint on fake leather upholstery, shower curtains, and air mattresses. These are the surfaces of the everyday that try to evoke opulence. This flesh of proletariat consumables is then stretched over an irregular support, while serving as the platform for today’s mythos.

Ali Seradge, Scheherazade of the Greater Southwest,

rope and oil on fake leather, 30″ x 24”, 2018

Ali Seradge, Recursive Beast, Oil, designer fabric, foam, tin wire, on found wood, 58”x36”, 2018

Can we talk about the painting Recursive Beast (2018)? In this, you are pairing recognizable imagery (a wolf, heads, outlines of hands) with abstract formal elements that is surrounded by foam pierced with tin wire. Can you walk us through the production of your paintings?

Absolutely. I’ll walk through the creation of that piece, as it is indicative of my painting method. The myth of Rostam’s Third of the Seven Labors from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh sits at the core of this painting . A dragon approaches the hero while he sleeps and Rakhsh, his horse, wakes him twice but the monster cannot be seen. On the third iteration, there is enough light for the hero to perceive the beast and kill it. I view this as an allegory for the mind let loose. It takes an awareness of what is concrete and real, like the horse is aware, to rouse suspicion in the drifting/dreaming mind. We are able to surmount this mental spiral when reason or the conscious mind, represented by daybreak, are brought in at the behest of our worldly senses.

The Recursive Beast is the dragon. It’s a pitfall that can beset anyone. The thoughts become recursive, meta, and self-serving until you are separated from your surrounding reality. So this alligator/wolf in a kid’s red shirt and cap, with human heads for eyes is a direct reference to that hypnotic serpent. The fabric was perfect because it creates a video screen type effect. It looks like a creature that might live in neon or an old video game, burping shower curtain chi-smoke. The elements around it I added to reinforce the idea of a telescoping reality, and one that intrudes on our own. The foam with the tin wire I represent the dust ball that forms when cartoon characters are fighting. The linen backdrop behind the dustball is a splash frame that is used to promote ads in comics. All of it is an effort to depict a Div or demon that is the embodiment of dangerous and wasteful recursive thoughts. It is an ever present temptation that moves through all media. Right now, a lot of that danger is based in screens and echo chambers.

This way of working through an idea is most common with my paintings. I have a bagful of myths and creatures that I use to relay these kinds of messages. The formal, material, and image considerations are always in service to that primary idea.

Ali Seradge, God Is Fake Drones Are Real, oil, charcoal on fabric, 23”x27”, 2017

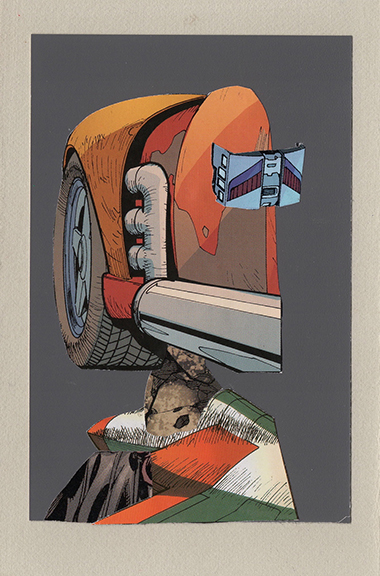

In addition to your paintings your regularly produce collages. In the series, Dog Star War Refugee, I want to translate the content into portraits due to the title and appearance of the imagery. What is the intent in these works? Is there a connection with these works to that of your paintings?

They should be read as portraits or maybe more like documentation, like passport photos in a file. The collages are made from my old comic collection, almost everyone has cuts from The Transformers franchise. That’s important because of the nature of the series and when it debuted. Transformers is actually a narrative mapped onto a set of toys leftover from the Diaclone line. The toys were in existence, then Hasbro laid everything on top of it. That cartoon hit the airwaves in 1984, when the Iran – Iraq war was at it’s halfway point. This was the start of “The War of the Cities.” My mom always had news from the war playing during the day, and I would catch the cartoons when that wasn’t on. So I had a real war over oil airing alongside fictionalized war over “Energon,” which is like space oil. The U.S. capitalistic market had self serving interests in both.

So I take a knife to that fetishized bit of childhood and create a catalogue of refugees from various interplanetary conflicts, as a sci-fi stand in for the displaced individuals that have become the long term consequence of U.S. intervention abroad. So, yeah, they are super related to the paintings. Especially the ones related to the dangers of looking back, which serves as a literal warning to those fleeing danger, but also an allegory against nostalgia and attachment to the physical trappings of childhood. An artist should be able to cannibalize that with cold purpose to build something for the future.

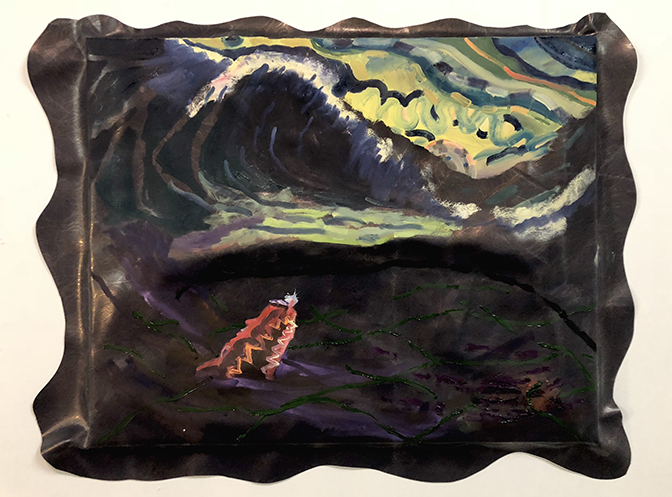

Ali Seradge, Dog Star War Refugee 062, comics and paper, 11”x6.5”, 2017

What do you value most in your aesthetic practice?

My audience, which aside from my peers and the nebulously defined art world, is the general public. I rarely see them, but I do like interacting with them when I can. It’s important to give them credit and not underestimate them. I like to hear what they have to say. And when they express an opinion or concern, it is important to listen. I see a lot of artists be very dismissive of critics, but even more so of the general public. I don’t know where that comes from, but it really does a disservice to both parties.

Ali Seradge, Dog Star War Refugee 008, comics and paper, 6”x4”, 2017

2018 is swiftly coming to an end. Do you have any specific projects you are hoping to call closure to? What’s the plan for the new year?

Oh my. No, unfortunately, I don’t see any end to the migrant crisis coming soon, I don’t see an end to the lot of the ills I try to address in my painting. If they did, I’d find more. I want all my projects to keep running. It always feels like I am just getting started. I have multiple video installations in the works. Next year, expect to see some installations from PIXELFACE (a collaboration with KT Duffy.) Also, I am part of a gallery called Langer/Dickie (@langeroverdickie), so keep an eye on that. And within the next 5 years Chicago Art Union should be picking up steam, providing high level secondary school and practical art knowledge for fucking free. Suck it overpriced art schools! lol.

For additional information on the painting practice of Ali Seradge, please view:

Ali Seradge – http://www.aliseradge.com/

Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/aseradge/

Patreon – https://www.patreon.com/aliseradge

Twitter – https://twitter.com/aseradge

Ali Seradge, painter, East Garfield Park, Chicago, 2018

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello