Immersing herself in a deep contemplative aesthetic practice focused upon our ever-shifting environment, Alice Q. Hargrave has been producing thoughtful photographs that offer lush, color-soaked and attentive meditations for the better part of 30 years. This week, The COMP Magazine visited Hargrave’s expansive and highly organized Bucktown studio to discuss her recent published book, Paradise Wavering, her process of making photographs, what she values most in her art practice, her tenure as an educator and her ongoing investigations.

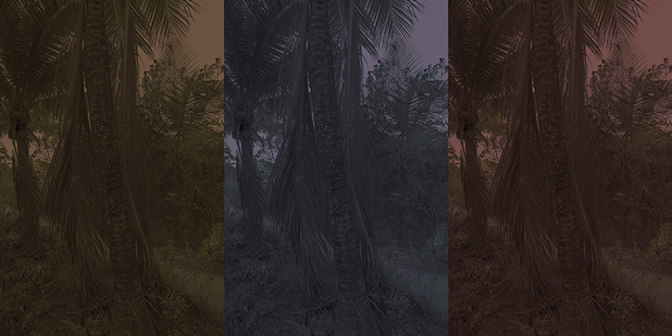

Alice Q. Hargrave, The Difference of a Day, 2016, pigment print, 20” x 39”

You’ve been rather busy in recent time with the publishing of Paradise Wavering and the production of the accompanying exhibition at the Hyde Park Art Center. I am curious if we can back track a bit? Perhaps, you can offer a little history to how you’ve arrived at this point? Are there any early experiences or people who have assisted you in your current aesthetic practice?

I have been making art work consistently since 1986 when I started the first project that I took seriously—which reflected on the organic world and how it manifested itself in the work of Antonio Gaudi. I was living in Barcelona and working for six months on a very B film that barely made it to video. I was in charge of props and worked with the art department, which allowed me time to explore Barcelona and experience its truly remarkable architecture. I studied art, architecture and film as an undergraduate, and became enamored with Gaudi, which led to a body of work called The Architecture of Memory. The Chicago Cultural Center was instrumental to my career, as they offered me an extensive one-person exhibition of this work in 1991, before graduate school–and then later, after graduate school (MFA from UIC in 1994), they offered me another one-person exhibition in 1998 titled Fecundity.

The natural world, our relationships to it, as well as memory have all been themes in the work since the onset of my artistic exploration — there have been many similar questions over the years, but approached from very differing perspectives. This quote from George Sand was included in my very early artist statements and it is still relevant today: “The consciousness of self as animal, vegetable, and mineral, and the delight we feel in plunging down into that consciousness, is by no means degrading. It is good to know the fundamental life at our roots…”

The Museum of Contemporary Photography has also been a great supporter of the work, purchasing three pieces in the mid 1990’s after giving me an opportunity to do a large installation, consisting of 50 photographs, as part of their Sciencia Artifex exhibition in 1997. Carol Ehlers Gallery represented the work at this time, so I am indebted to her, as well as the wonderful UIC graduate school environment with Judith Kirschner at the helm. Julia Fish was one of my graduate advisors. Working with her, thinking about the relationship between painting and photography, keen observation, and the delicate border between abstraction and representation was an important part of my growth as an artist.

Alice Q. Hargrave, cover of Paradise Wavering, Daylight Press, 2016

Tell us about Paradise Wavering. What was the impetus for this investigation? Where have you made these images? What was the intent?

The title Paradise Wavering refers to the fragility and vulnerability of nature. Paradise is a myth, it is in flux, it is tenuous and, like memory elusive. I chose that title to underline my concerns about climate change and how I cannot immerse myself into these natural environments without addressing our role in today’s environmental crises. While immersing myself in the beauty and sublime of the natural world, I also want to reference the dichotomy of nature being at once an unrelenting force–sheer power, but also vulnerable to our many interventions.

The book Paradise Wavering incorporates earlier work from my Home (Movies) series, and this stream of consciousness of images move in and out between different places and time periods, becoming a non-linear trajectory–like our minds, which also don’t function within constraining borders of time and space.

Alice Q. Hargrave, Esperanza, 2015, pigment print , 43” x 62”

In much of the recent large-scale works (e.g., Biosphere, #1; Esperanza; Shade) I see a specific focus in your subtle use of color. The images are essentially monochromatic with silhouettes of tonal details (e.g., palm leaves and foliage). What are you attempting to convey with this limited color palette?

The cusp between lightness and darkness fascinates me. I love that in-between time that is neither day nor night, the intensity of the almost night sky, the deep greenish blues–all of which underscore for me the passage of time. Moments of darkness just before nightfall, when deep shadows are somewhat illuminated, but are steadily being usurped by the dark. This movement mirrors the corners of the mind filled with faint memories. Dusk, being so fleeting, is analogous to the sense of loss we are constantly facing as we feel life racing by–the loss of a moment, a single day, a childhood, a person or an entire lifetime. For me, there is a certain beauty in this “capture” which photographs attempt to do. But then there is the subsequent, inevitable loss characteristic to photography itself, which makes it a perfect tool for probing the fugitive nature of childhood, youth, memory, and the changing landscape.

Alice Q. Hargrave, exhibition view of Paradise Wavering, Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, IL 2016

What do you value most in your art practice?

I value the opportunity to slow down, to look, to feel, to think about things, to reflect on the world at large and my place in it, to think about making connections to the natural, organic world. Reading both fiction and non-fiction informs my practice. I love reading poetry–Pablo Neruda and his odes, for example. But much of the work is also informed by current events, mostly in the realm of the environment. Every morning, when I sit down to work, my browser opens up to an image of some new environmental nightmare–like the frighteningly vivid orange waters of the Animas River in Colorado after it was tainted from a mining waste incident. Or images of dry river beds, from California to Iran, where one picture showed beached swan boats now lying on the ground.

I love all aspects of the photographic process. I love the taking of the photographs, immersing myself into subjects or the natural world, while trying to begin to understand their complexity, and the various roles and interconnectivity of plant and animal life. Also printing is a creative and experimental aspect of my working process–changes in color, light and densities change the whole emotional charge of the images.

I seek the sublime, both close to home and further afield. The work is about prolonging and savoring experience, about finding something rare and noticing. About reverie, daydreaming, desire, loss, and an urgency for calm. The book and the images are also about deep looking, both inside and out–I want you to get lost in the imagery.

Speaking of “lost,” this quote from Rebecca Solnit from her seminal book A Field Guide to Getting Lost is one of the passages that I used to bookend the stream of photographs: “Like cards, flora and fauna could be read again and again, not only alone but in combination, in the endlessly shifting combinations of nature that tells its own stories and colors ours, a nature we are losing without even knowing the extent of that loss.”

Alice Q. Hargrave, exhibition view of Paradise Wavering, Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, IL 2016

Installation photograph by Tom Van Eynde

You also have a long history as an educator. You have taught at Columbia College Chicago since the mid 1990s, and prior to this you taught at SAIC, UIC, and the Marwen Foundation. Are there specific ideas and practices that you regularly share with your students?

One thing that comes to mind is I emphasize to my students the importance of seeing work in person! In order to fully get the experience of work, one, if at all possible, should place themselves in front of it. Textures, scale, surface and many other formal qualities just cannot translate in reproduction. I am quite meticulous in my printing and emphasize the importance of knowing how to make great prints, to know the rules well and then break them when necessary. There’s the adage that form follows function–what form should they use to best convey their individual messages? I want them to be able to make prints that rival and can surpass any analog precedent.

I also encourage students to not only look at work within their chosen media, but to look, study and read outside of their mediums–to find links of intent, for example, with a painter or videographer or author, and to cross those borders in order to enrich their own practice and knowledge base.

Alice Q. Hargrave, Lichen, 2015, pigment print, 30” x 40”

What’s the plan for the remainder of 2016 and the future? Do you have any current new work or are you planning to extend your current investigations?

I am continuing a series of abstract studio constructions, working with the curvilinear-shaped stencils from my husband’s painting practice, along with other residual elements of artistic practice. Many of the hues and forms reflect or echo elements of the organic world.

I am also working on images of plant life at night, and working with the many images I recently made in the southern most tip of Costa Rica about biodiversity and the incredibly lush and primordial cloud forests.

Additional photographs by Alice Q. Hargrave:

Alice Q. Hargrave, Visages Oubliés #2, 2015, pigment print, 30” x 24”

Alice Q. Hargrave, Biosphere, 2015, pigment print, 43” x 64”

Alice Q. Hargrave, Spray, 2014, pigment print, 56” x 44”

Alice Q. Hargrave, Grizzly, 2015, pigment print, 14” x 14”

For additional information on the photography and practice of Alice Q. Hargrave, please visit:

Alice Q. Hargrave – http://www.alicehargrave.com/

Hyde Park Art Center – http://www.hydeparkart.org/exhibitions/alice-hargrave-emparadise-waveringem

L’Oeil de la Photographie – http://www.loeildelaphotographie.com/en/2016/07/12/article/159914213/alice-q-hargrave-paradise-wavering/

Daylight Books – https://daylightbooks.org/products/paradise-wavering

Alice Q. Hargrave’s monograph Paradise Wavering: Limited Edition Prints and Books – http://www.alicehargrave.com/publications-products/paradise-wavering

Classic Chicago Magazine – http://www.classicchicagomagazine.com/alice-hargrave-paradise-wavering/

New City Review – http://art.newcity.com/2016/06/03/vivid-colors-wash-over-memories-a-review-of-alice-hargrave-at-the-hyde-park-art-center/

Museum of Contemporary Photography Chicago – http://www.mocp.org/collection-artists.php?c=h

MoCP Fine Print Program – http://shop.mocp.org/collections/fine-prints/products/hargrave-alice

Alice Q. Hargrave, photographer, Chicago, IL 2016

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello