Working in an array of styles that utilize classical medieval traditions to hyper-modern aesthetics and technology, Andrei Rabodzeenko cultivates an intricate cosmology that navigates abstraction to narrative driven dialogues in his contemporary art practice. The work is densely layered, meticulously polished, and quite beautiful. The COMP Magazine recently caught up with Rabodzeenko to discuss his solo show at LUMA, his fascination with metaphysics, and humanity’s ongoing obsession with post-apocalyptic themes today.

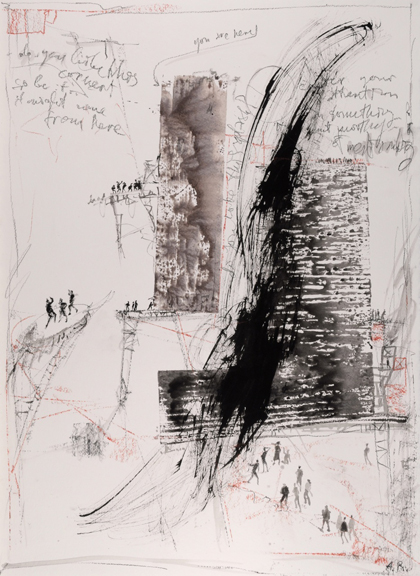

Andrei Rabodzeenko, Legend of Daedalus, 2014

Can we start with your background? You grew up in the Soviet Union and immigrated to the United States in 1991. How has this move impacted your artistic practice? Did you see a shift in what you wanted to investigate upon arrival?

Back in Russia I worked as an architect and interior designer. I did some art there, but more on the side. When I moved to the US, I devoted all my time to painting and drawing. I felt this sense of freedom coming from everywhere — streets were more open, there was lots of light, sun. Places were less crowded. Also, I had this feeling that I could draw whatever I wanted, experiment and let my own judgment decide. I can’t say that in St. Petersburg somebody dictated what to draw. But here I let my inner-self open up fully. I felt that the local native spirits visited me and entered my inner world.

Andrei Rabodzeenko, Ascent, 2015

You currently have a solo exhibit, Technotropic Romance, at the Loyola University Museum of Art in Chicago until August 2, 2015. The work in this show references Armageddon and apocalyptic themes. What prompted these investigations? Can you discuss your process? Specifically, how are you approaching and merging spontaneous and realist drawing styles?

The Armageddon theme is in the air. You don’t have to go far for it. The post-apocalyptic theme occupies a permanent place in movies and books. At the same time the theme is not new, the Bible already has chapters on the topic, like the Tower of Babel, which caught my attention by the similarity with our time, when we are so preoccupied with technology, building our “tower” higher and higher, forgetting about our inner spiritual and moral development. And living in this time, I have my own feelings towards this topic, some thoughts that I can’t hold back, but have to express through the means that is close to me, that is — art.

Andrei Rabodzeenko, New Babylonians 03, 2014

For some time I worked in a classical style of oil painting, which requires planning, precise drawing, careful application of paint. Probably I arrived at a point when I had accumulated enough wild energy to release it in a spontaneous manner. I let my feelings take over the process. But at the same time I wanted to create a nervous blend, an argument between spontaneous and controlled, or semi-controlled. I made drawings of figures surrounded by spontaneous lines and splashes of emotion, bordering on despair, but at the same time — strength. Sometimes I would just start with a splash of paint, but everything happens almost immediately, one following another by a fraction of a second. The whole mood of the picture already almost happened in my head. I think my traditional or classical art education helps (I don’t like word training — I think it belongs to sports, something physical, non-intellectual). My hand does what almost everything that my mind, or the feeling part of me, wants.

Andrei Rabodzeenko

New Babylonians 01

2014

The topic of metaphysics appears to be a key interest in your art practice. This subject has a rich history dating back to the early 20th c. art (e.g., Giorgio de Chirico). Often, I see a assemblage of crude markings and symbols that invite varied interpretation. Can you share with us your working process?

The subject of metaphysics begins out of a certain understanding of the world that probably has roots in prehistoric time, stone age. The surrounding world appears to be alive in all its manifestations. Thoughts about people, memories of events, and thoughts themselves materialize in physical forms. They become part of our everyday life, because they are part of it. Here, I allow spontaneous manifestations to appear and be as vivid, concrete or just a hint of a phrase, dimly lit image. They are ghosts that talk, act, and take any shape they want. They can be scary or funny, harmless, or …

Andrei Rabodzeenko, Take, 2013

In your studies of archetypes, there is frequently a referencing and sense that reminds me of medieval painting. For instance, in “Legend of Daedalus” (2014), the work is a triptych with iconography and individuals that dressed and interacting as if they are from the noted period. What is your fascination with seemingly antiquated (yet beautiful) style of painting?

Aside from its obvious beauty, medieval or early European Renaissance style gave me an opportunity to distance myself from todayness. I wanted to look at my time from some height, like a tower. I even went through a sort of physical transformation — for two years I put myself on a cultural diet. I stopped watching any moving images (movies, TV…), stopped listening to any rhythmical music (jazz, rock…), and stopped listening to any music as background. I immersed myself in medieval literature and music: The Canterbury Tales, The Divine Comedy, St. Augustine’s Confessions, Hildegard Von Bingen, The Return of Martin Guerre, … the Bible.

This “diet” gave me very interesting results. I really started seeing the world differently. I became closer to an understanding of how artists of that time saw things. The world became more physical, and I became closer to the material world around me. At the same time my sense of spirituality became natural, obvious and almost necessary.

Andrei Rabodzeenko, Thrill, 2013

So after that transformation, the now appeared in a sharper light, like in a 3D movie.

I also think that in early Renaissance painting, an important balance was achieved. It’s like a violin — not changed for centuries — so perfect an instrument, which allows the expression of minute movements of the human and above-human, and still has the potential for much more. So, as the human realm is one main subject of my creative research, this style allows me to express it all and never hit a dead end (as an expressive tool).

It also involves a measure of rebellion against modern trends in art. It’s a challenge to contemporary viewers — to put them face to face with something made today, yet carrying timeless values in a form that is detached from today, as if to say, “without your technology, which you cover yourself with like armor, you are just a naked human being, the same as centuries ago.”

Andrei Rabodzeenko, Run, 2012

What are you currently working upon? Do you have any upcoming exhibitions or projects in the works?

This fall, I’m curating a show with a few artists that I like. The title of the show will be IN SANE. It will target our understanding of sanity and insanity in a social sense. I also will include my own work in this show, an installation and an audio-visual performance.

And at the end of September I’m having a show at St. Xavier University featuring the “Technotropic Romance” graphic work that was at LUMA. Maybe there will be some changes in work and the title of the show.

Andrei Rabodzeenko, Wing, 2006, Skokie Northshore Sculpture Park

To view additional information on the work of Andrei Rabodzeenko, please visit:

Andrei Rabodzeenko – http://www.rabodzeenko.com

Color of Change at Terra Sounds School of Music & Art (video) – https://youtu.be/cRgs27M5-l0

Andrei Rabodzeenko Becoming (video) – https://youtu.be/XuneSat28g8

Andrei Rabodzeenko, artist, Evergreen Park, IL, 2016

Interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello