Angelo Mantas has been making photographs in Chicago (and beyond) for more than 5 decades. This week The COMP Magazine caught up with Mantas in the South Loop to chat about growing up in the city (during the the last century), how his photography inquiry has changed over his extended career, the role his teaching plays in informing his practice, his love of hang gliding, and how casual walks can provide interesting visual materials.

We’ve known each other since the mid 1990s. You grew up in Chicago in a Greek family? Let’s jump back a bit. Can you share with us any experiences or people who you see as initiating your interest in photography?

Wayback in 1962, I went to Greece with my parents. I was seven years old. My dad had an old rangefinder camera. Even at that age, I had something of an artistic bent, and I was also very interested in science and technology, so the camera appealed to me. It’s hard to tell who took which shots, me or my dad, but there is a picture of both of my parents that I took on the way to a monastery. It’s in black-and-white, my mom looks very young, but my dad already looks middle-aged, a little on the heavy side, and balding. I’m thinking about a book on my parents struggle with Alzheimer’s and dementia, if I proceed with that, that will be the first photo. Then, not much use of the camera beyond the usual snapshots, until I got into college. After a sketchy three-year stint at N.I.U., I was looking for a reset and decided on photography. I transferred to the Cinema & Photography program at S.I.U. Dave Gilmore was my first photo teacher, and he made a big impression, showing me the possibilities of that medium. We still connect on Facebook every now and then.

You did a show at USF’s Moser Performing Arts Center back in 2001. Can you describe your development as a photographer over the past 20+ years? Has there been a shift in focus in terms of content? New technology?

Dave Gilmore, in talking about ways to describe photographs, said one way to look at them was that they could be synthetical or analytical. My show at USF was synthetical, in that I was combining many elements to make a new visual construction. Since then, my work has become more analytical, the idea of using the camera to really focus in and examine a particular subject. Technically, I’ve gone from black-and-white film, to Color film, to digital. Sold my Leica and Nikon film cameras years ago, now I have a portable Sony with Zeiss optics, but I shoot a LOT with my iPhone, including all my panoramas. The best camera is the one you have with you.

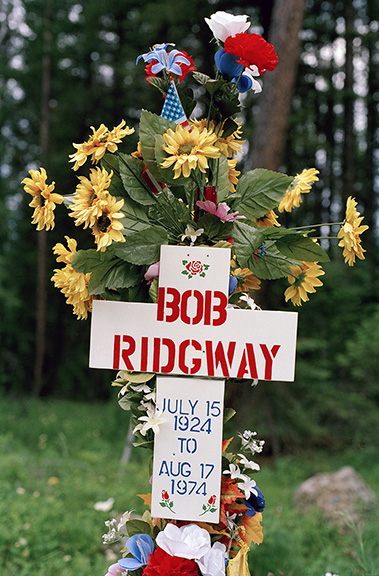

You try to travel frequently. In these sojourns you have been compiling a series of images that document roadside memorials? Why did you begin the series? What are you attempting to convey to the viewer?

As you say, I travel a lot. Usually by car, road trips. First out west, then more around home, I noticed these roadside memorials. I’d seen them for years, maybe a decade or more, before stopping and looking at one. I was really taken in, the care and ingenuity that went into making these really impressed me. Also the emotional level, these were sites of tragedies. Death is something we keep far away from ourselves in our culture. Those who are dying are either in hospitals or nursing homes, it’s not something that’s right in front of us. With roadside memorials, the heartbreak of death is thrust upon us, it’s in our every day living spaces. The offerings to the dead, the heartfelt messages, the way people were sharing their grief with anyone who happened to go by, touched me. So I started photographing them. I’ve got literally hundreds of these, from New Hampshire to San Diego, Wisconsin to Texas. A good portion of these are on colour negative film, so I need to get serious about editing those down to ones I want to scan, and getting them ready to print. I plan on putting out a book of these soon. I had an exhibit of these in Florida roughly 10 years ago, Jno Cook wrote the intro to the show. He was very supportive of the work, and I want to dedicate the book to him.

You are an avid practitioner of hang gliding. You have been working on a book about your experiences. Can you speak to this effort?

The following is from the “Introduction”:

There are a lot of misconceptions and misleading myths about hang gliding, part of what I want to do with this book is address those. Many think it’s an adrenaline sport, but the best flying is those calm, transcendent moments when everything is unfolding slowly in front of you. It can be dangerous, but no one in this sport has a “death wish”, tempting fate is the last thing we want to do.

I think the thing that most surprises people about hang gliding is that we don’t just take off from the highest point we can find, then glide down to the bottom. The goal of every pilot is to find lift and stay up. Weather conditions aren’t always conducive to this, but on a good day, you can stay up for hours, gliding from cloud to cloud (clouds are created by lifting air). There have been days where the lift was so plentiful, I’ve had a hard time getting down. Most people are shocked to hear my longest flight is four and a half hours, that I’ve traveled 85 miles, or that I get a mile up or higher on a regular basis.

What makes these events fantastic is that you are out there. You hang below the wing, out in the open, not cocooned up in metal and glass like an airplane or glider. With nothing to block your vision, the view is just incredible, the whole world spread out before you, the wind in your face. It’s as close to flying like a bird that man will ever come.

In recent time you have been photographing seemingly random items (flags, pacifiers, roadkill) you find during walks. What prompted this?

Five or so years ago, I was crossing the street in Red Lodge Montana. My eye was caught by a smashed bird in the middle of the street. It had been there a while, run over multiple times. It was totally dried out and desiccated, so there wasn’t really any gore. The beak had been smashed into multiple bits, making it look like several beaks side-by-side, and the rest of the body was splayed out at all these crazy angles. It looked like a cross between that famous fossil of Archaeopteryx, and a Picasso. I called it Cubist Bird. It didn’t fit with anything else I was doing, so it kind of sat on the shelf. Recently, I was doing walks with my partner Nancy. As we waked around the neighborhood, I started to notice objects on the streets. All kinds of objects, lost toys, smashed animals, strange markings, discarded liquor bottles, other interesting (to me) items. So, I did what any photographer would do, I started photographing them. Someone once said that to photograph something, is to make it important. I find these objects interesting. Today, photography is very much about the constructed, pre-planned image, but when I learned, it was about going out into the world and finding images. That’s what I’m doing here, my own personal visual treasure hunt.

You have been an educator for more than 20 years. What are some of the consistent items you hope to demonstrate to your students?

The thing that photography has taught me is how to see, noticing what others miss, because most people are so far into their own heads they literally do not see what is right around them. It’s really a very Zen thing, I feel this is the most important thing I teach my students, to slow down and really look and see the world around them.

What are you currently working upon? Do you have any specific projects or ideas you are currently developing?

A few off and on projects going on. I’ve been exploring the panorama format, where the photo is super wide and can take in a 180 degree, or more, view. I’m printing these between 4 and 6 feet wide, they need to be huge in order to do them any justice. Store facades interest me, I’m slowly accumulating a body of those. I’ve already mentioned the street objects, the memorial series needs to be wrapped up, and I’m contemplating a return to portraits, which was all I did for 15 years or so, but haven’t done much of since the ‘90s.

Interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello