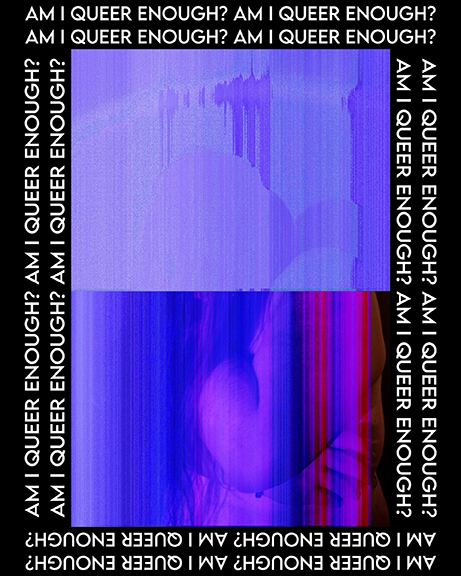

We live in a time of where identity and self-reflection have become common themes in aesthetic inquiry. In this, youthful spirits are taxed with sorting through the past, identifying misnomers, addressing present day crisis, and creating new formats in one’s studio art practice. Ash Huse is a graduate student in the Photography Department at the Columbia College Chicago. They examine the noted through photographing and examining themselves and those that travel within their intimate circles. Through contrasting their queerness, the history of self-portraiture, and manipulating digital files, the appearance of an uncanny disintegration ensues. This week the COMP Magazine trotted over to the graduate studios on Michigan Avenue to discuss with Huse their coupling of portraiture with new digital techniques, how they define themselves as an image creator, the role photography history and previous practitioners play in their inquiry, and what they value most in their current lens-based research.

You grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, and moved to Chicago a few years ago. Can we start with a summary background? How did you land in Chicago? What role did the arts play in your youth?

So, when I was young, I had always watched my dad lug around a camera (disposable mostly but he did also use a 35mm) and a video camera all the time. The mall, vacations, the zoo, school and even in our own living room he would be capturing all of these little moments in order to put them into scrapbooks, or just generally documenting his kids growing up. I always admired his desire to capture the beauty of the world around him, he could go to the same location over and over again and keep finding new things to discover and photograph; it wasn’t until I grew up and reflected on it more than I had found it really endearing and it did, in a big way influence my own path into using lens based technologies to talk about issues in my life. It was when I was in middle school that my father had let me take his little point and shoot digital camera; just messing around mostly, but I was enjoying using the camera with my friends and how we almost performed differently for it, knowing it was there. I was asked if I wanted to be part of the Yearbook Club and so I started shooting a bunch of events around my middle school and it went on from there to high school where I got more serious and wanted to expand my newfound love for photography. I originally wanted to go to LA, when I thought I wanted to do editorial photography but chose Chicago, had some issues with the first school I went to, transferred to Columbia College Chicago for the rest of my undergrad and now here I am back for graduate school.

You define yourself as a queer lens-based artist, rather than as a photographer. Can you offer insight into this way of defining yourself as a creator?

For me when I had initially started out my photographic career (pre-COVID) I had been experimenting with a lot of techniques that don’t just stem from a photograph to simple print. I was trying my hand at various experimental techniques that would result in photographic objects. I felt like the scope of what people’s idea of photography is so limiting that I had the need to define myself by a more applicable term. While my medium of choice is still photography, I don’t want people’s preconceptions as to what a queer photographer is/can be.

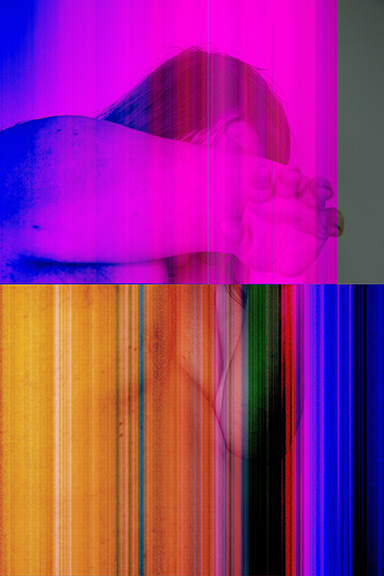

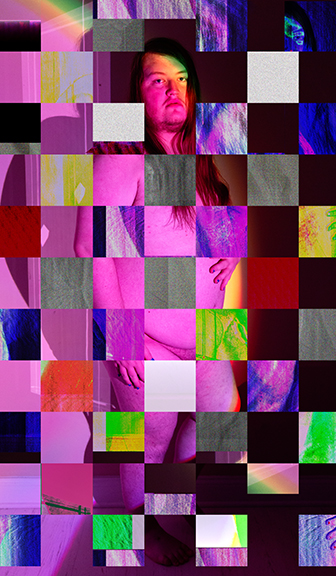

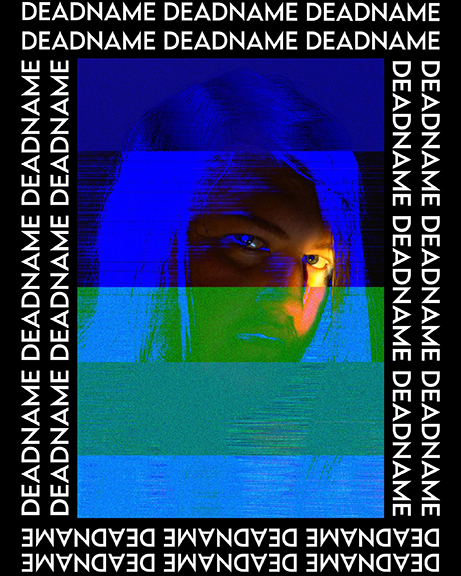

I’m fascinated by the technical process you employ when producing work. You are making images, then opening the files in a text editing application, altering the code, then printing the images. Can you discuss your process and the decisions that drive this form of aesthetic investigation?

I’m a bit of a photographic nerd, I really find the under the hood aspects of photography really interesting and how computers interpret photographic data. Before I had even applied to graduate school I had been fascinated by corrupted digital data. I was in a rather dark place between finishing undergrad in December of 2019 and all through COVID, before grad school. I had been so angry with my situation and what COVID had done to my practice and as a result the art world as a whole. I wanted to destroy my images, like the cliché people do in the movies by ripping up everything but I didn’t have any prints. I then learned about corrupting images to make weird and yet exciting abstracts from them. The original technique I employed was importing the images into a free audio software known as Audacity. You can see your images as a wavelength on this timeline, audible photographs. From there you can randomly select certain parts of the wavelength and manipulate it with effects provided through audacity. When you export them, they create these corrupted new images that I fell in love with. I didn’t really know why I was so drawn to this new mode of image making but I wanted to explore it further and employ it into my own practice. During my time at grad school, I had kept trying new ways of creating work with the music software and, while it’s been a great steppingstone, I have a hard time “staying still” so to speak and wanted to find new ways to corrupt images and experiment with that. It was through actually opening your images as text files that I had found a breakthrough. Through these 15,000 pages of code, you can find strings of letters, like “A,B,C” and the max string of letters you can find is 3 letters. So, I would look through the file for examples of the first 3 letters of my Deadname (name given at birth), there would maybe be 14 instances of these letters, and replace it with my preferred name; and the image would become corrupted, and I found it so fascinating. The idea of taking this image and transforming it into this cavalcade of colors and lines. From these experiments I used it to talk about queer identity through the use of self-portraits.

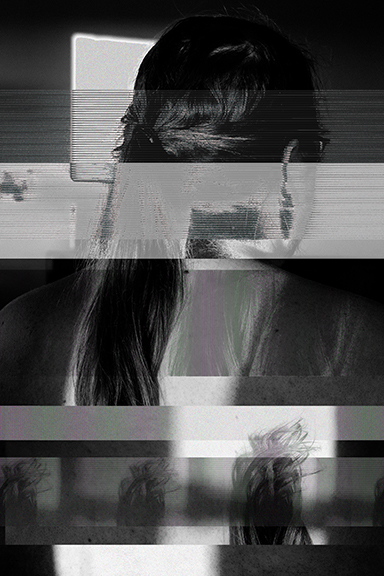

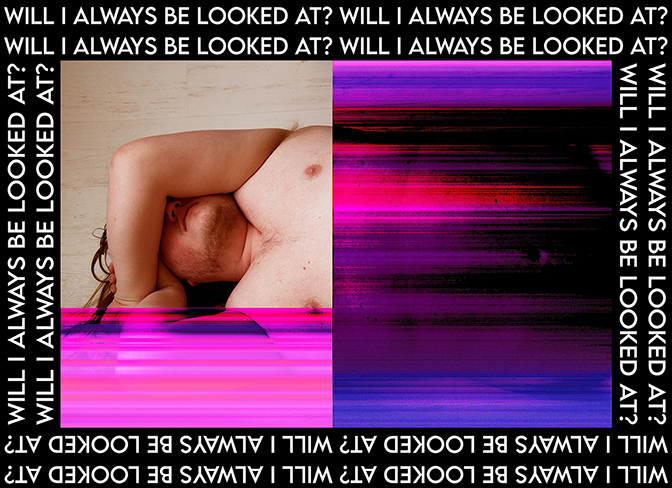

Currently, your primary subject is yourself. Self-portraiture has a long history (Jan van Eyck in 1433 to present practitioners like Cindy Sherman). Can you describe your intent and some of the ideas that drive your inquiry?

I have long used the camera as this tool to examine aspects of my life and help me parse through questions I have. Art has been that tool for me to ask these questions of self, representation, community, mental health. It’s been therapy in a way for me. Before I turned the camera on myself, I had photographed my boyfriend, Torrance, throughout my time in undergrad. Photographing gave me a better understanding of him and brought us together. I turned it on myself to finally allow me to talk about my issues rather than the issues around me; ironically it ends up being both of these things. I use the camera to remind myself that I’m a real person, with real emotions, real issues, flesh and bone. I have all of these questions internalized and I wanted to use the camera to direct them at whoever is viewing them to spark that curiosity in them.

What artists or photographers do you see informing your studio practice? Specifically, do you see any links to what you are investigating with past or present practitioners?

There are so many artists I see informing my studio practice, Nam June Paik, Laurance Rasti, Rana Young, Christopher Merrdo, Robert Mapplethorpe, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Jess T. Dugan and so many others. Many of the artists I look at are, typically queer photographers dealing with a lot of the same issues that I am when it comes to ideas of identity and representation through an artistic medium. Some like Nam June Paik and Christopher Meerdo employ technology as a means of better understanding societal norms and authorship.

What do you value most in your photo-based practice?

Community, bar none. I’m very much a person who thrives being part of a larger community. I’m a very anxious and introverted person but being able to work with people and communicate about my work and produce with people around me ultimately makes me a better artist. I used to be a lab assistant at Latitude Chicago and that community really helped nurture my artist career; I was very privileged and fortunate to be part of it. Everything was ripped away from me during the pandemic, jobs, inspiration, desire to make work but most of all, community. I was really fortunate once again to come back to Columbia for my master’s degree and to find that community again through the school and working at the Museum of Contemporary Photography. It’s been a long process on the road to recovery in that way.

What’s the plan for summer 2023? I believe you are heading into your final year of your MFA in Photography at Columbia College Chicago. Do you have any specific goals outlined for the future?

I’m about to wrap up my first year of graduate school, which has been really exciting and great. I’ve learned an incalculable number of things that will ultimately make me a better artist. I was actually fortunate enough to have my other project be selected for the Stuart Abelson Research Fellowship. Essentially that means I get a grant to go out of the country to make a body of work. I’m going to Vancouver for two and a half weeks to photograph my partner, Jamie who has been with me even before the pandemic started but they were really integral to me navigating my queer identity. For my second year I absolutely want to explore more ways to experiment with my work in relation to technology, use of text, design etc. all things I’ve never really been that well versed in; but I’m really excited for what the future holds for my career, art, and self.

Follow Ash Huse on Instagram: @ash.huse

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello