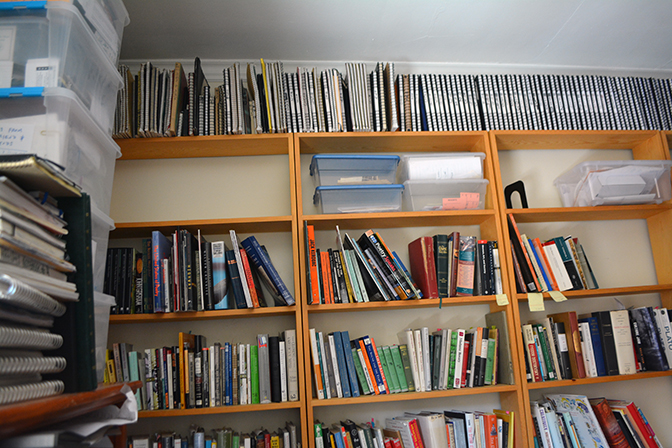

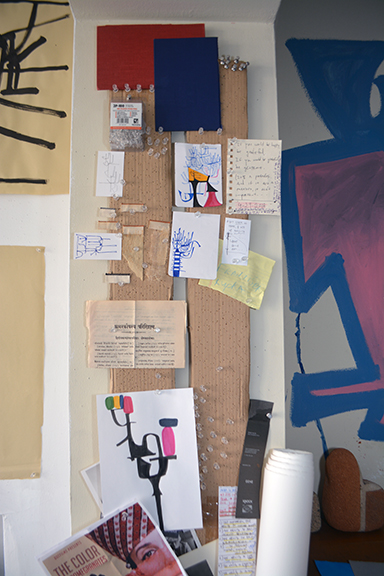

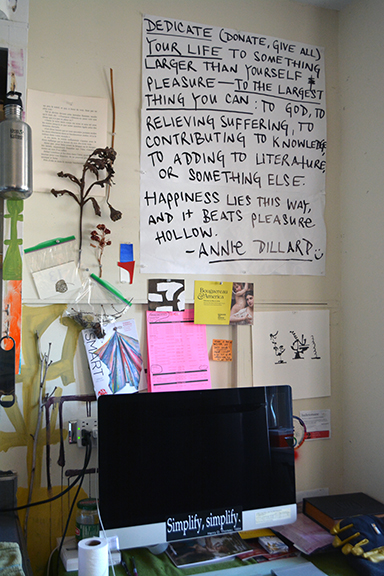

Upon entering the home and studio of Brian Russo one will immediately sense that a voracious search for wisdom is underway. All rooms are filled with books on art, philosophy, poetry, and psychology, and all surfaces are covered with artworks and inspiring ephemera. Russo’s aesthetic practice merges literature and a visual application to form a lexicon that is highly personal, yet filled with entry points that are truly universal. This week the COMP Magazine traveled down to Hyde Park to discuss with Russo his turbulent teens and transient twenties, his paradigm shift from focusing on writing to visual art, the role social media plays in disseminating his practice, and what he values most in his artistic investigations.

You grew up out near Midway, ran with some colorful rough characters, then joined the military, and travelled. One of the items that stands out in your background is how you transcended this environment. Can we start with a little background? Where and when did you identify the arts as something you wanted to invest yourself in?

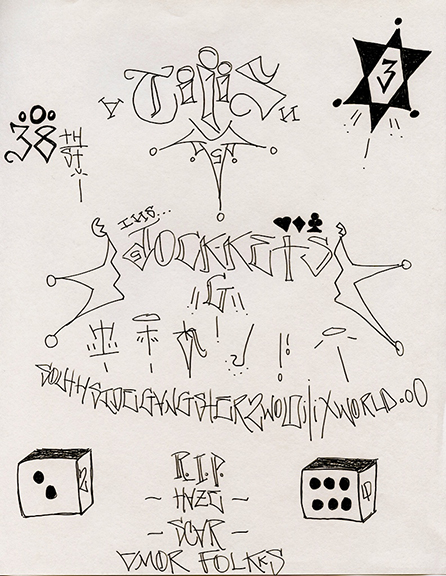

My early life is a long story. But if we jump to, say, fifteen or sixteen years old, yes: I was a high-school dropout sleeping in the unfinished basements of friends’ houses around Lawler Park—immediately south of Midway Airport. All my friends were high-school dropouts, and all of us were going nowhere fast. But it was pretty benign stuff, just sleeping all day and partying all night. Nothing sinister. Gradually, however, I became close with a gang member who went by the name of Little Jokker.

Jokker had ties to very different neighborhoods, such as Brighton Park and the Pilsen of the early 1990s. He introduced me to a vast symbolic world that I was immensely attracted to. The colors, the secret handshakes, the nicknames, the gang signs, the lingo, the graffiti—every detail of gang life is charged with creativity and a life-or-death meaning. I loved all that stuff. And I liked how it allowed me to do something ostensibly soft and gentle, like sitting quietly and drawing, yet still feel like a tough guy, because what I was drawing were these gang symbols that were full of pride and arrogance and lethal threats. So, sure: I was a lost kid and it was thrilling to carry guns and hang out with drug dealers and play cops and robbers on the streets of Chicago for a while. But what I know now that I didn’t know then is that it was the artistry of gang life that really appealed to me.

In truth I made a terrible gang member. Really I was a big phony. I could chameleon my way into playing the part, but I was mostly scared shitless on the streets of those tougher neighborhoods. And as I got to be seventeen and eighteen years old—old enough to go to real prison—and as I saw the people around me actually getting shot—I knew I had to change my life.

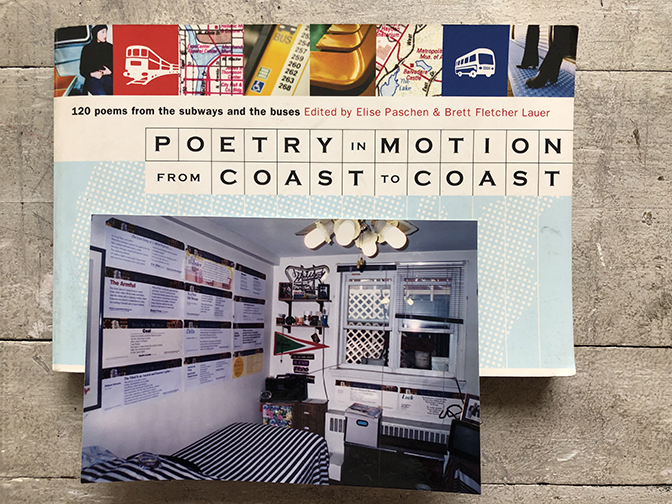

So I vanished. Long alienated from my family, I went to my dad and asked for help. He sent me to Brooklyn to live with an aunt whom I barely knew. I got my GED and worked odd jobs in the trades, and I started filling notebooks with words, trying to make sense of my life. I still had no notion that I was an artist or somehow meant to be one, but my eyes were always open, and I continued to absorb culture at the street level. I used to do this thing that I called my “solo token trips.” Every week I’d buy a little ten-pack bag of subway tokens and go get lost in New York. I’d get on the F-train at Avenue X and just ride around and transfer and explore at random. I’d end up in some dull neighborhood in Queens, or in Central Park, or wherever. I’d do things like sit on a park bench on the Brooklyn Bridge and drink a forty while making a long journal entry. Oddly enough, this is how I discovered poetry. New York City had a public arts program at the time—around 1995 or 1996—called Poetry in Motion. Sprinkled in among the advertisements in all the buses and train cars were these wide narrow posters with poems on them. And since I was always on public transportation, I was reading a lot of poetry. And it was great stuff: Shakespeare, Langston Hughes, Robert Frost, Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, T.S. Eliot, Gwendolyn Brooks. I started snagging the posters out of train cars and taping them to the walls of my bedroom.

I wanted to enroll in a few courses at Kingsborough Community College, in Sheepshead Bay, but I didn’t know what to take. I was considering the paralegal or physician’s-assistant programs because it seemed prestigious to work among lawyers or doctors. But really I was clueless. I had no idea what to do. Somebody told me not to worry about it and just to take a few general courses to get the hang of college and to get a few electives out of the way. So I took a journalism course, a modern-art history course, and a poetry course. I didn’t know much, but I knew I liked words and visual stimulation.

14 poetry posters filched from the F train

Those courses turned out to be perfect for me. They forced me to attend poetry readings and to visit museums. In 1996 I had a quickening experience at the Museum of Modern Art. A special exhibition of Roy DeCarava’s photographs astonished me. And to be astonished by a work of art, to stand before it truly moved and transfixed—truly energized and inspired—is to be somehow changed. It’s done something to you. It’s added something to you. You’ve been enriched, deepened. In any case, all of that happened to me with the work of Roy DeCarava. I had almost no money, but I still dropped the forty bucks on the exhibition catalogue for that show, and I still have it today. That 1996 Roy DeCarava exhibition at MoMA is what made me want to be an artist. But I’d never touched a paint brush, so I just assumed that my calling was photography and not painting or drawing or sculpture.

A year later I found myself in a small town on the peninsula of Washington state, where I joined the Marine Corps. There was some kind of tug-of-war going on within me between the inchoate longings of a sensitive young man and would-be artist, versus the macho cliché that I was raised to be. I signed up initially to be a USMC photojournalist (again with the words and images). But when someone in my family laughed at me for choosing such a sissy job when I could be blowing stuff up, I switched to the most hardcore job I could find: heavy machine-guns in an infantry unit. In a way this was a disaster. But, on the other hand, my time in the Marines gave me some odd and inspiring experiences. I met a bunch of distinct characters and got to know them well; I lived in California and got to train in the Pacific Ocean, the Sierra-Nevada mountains, and the Mojave Desert; I partied in Tijuana, Mexico; I visited Singapore and Thailand; and for seven months I was stationed in Japan—where I hiked to the top of Mt. Fuji. So: rich stuff, and a far cry from Lawler Park!

I believe your initial passion was literature? You have one of the largest libraries I have encountered. I believe there are mountains of books in every room. Can you tell us about your relationship to prose and poetry?

My initial passion in life was skateboarding, but that’s another story. I read my first book at twenty-one years old. It was Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. I loved it because I could identify with it. The stream-of-consciousness style resembled my own journal entries, and the content reflected the way I was living at the time. When I got out of the Marine Corps I was on a quest. I was searching for something, but I didn’t know what. I worked on a house-framing crew in Flowery Branch, Georgia. I worked at an art-supply store in San Francisco. I did hot-tar roofing in Reno, Nevada. But I was also, always, everywhere I went, drinking too much. Jung says the alcoholic is a frustrated mystic. It was easy for me to romanticize my chaos and confusion as a spiritual odyssey. But that was just a euphemism for my fear and self-ignorance. It’s exciting and macho to be on some deep and inscrutable journey. But it’s decidedly less romantic to admit that you’re just running scared and in flight from yourself. In Reno, just as I was gearing up to move to Alaska to try my luck on a fishing boat, I had a religious conversion. I’m laughing because I know it sounds crazy. And it was; it was wild and wooly stuff. After a disorienting few days of binge drinking, I came to in a little church where a preacher was reaching the emotional apex of his rhetoric. The sermon was culminating in an altar call. There was music and song. People were going up to the front to pray and be saved; to be liberated—to give their hearts to Jesus and be cleansed of all their sin and guilt and shame. And, with tears streaming down my face, I did the same. That was on September 9th, 2001. The next day I turned twenty-four years old. The day after that 9/11 happened.

Instead of Alaska, I moved back home to Chicago. But I lived in Uptown, on the northeast side rather than the southwest side. I joined The Moody Church and became a part-time missionary while studying literature and philosophy at Roosevelt University. All told, my religious faith lasted fewer than five years. But in that time I managed to go to the Czech Republic to convert atheists; to Poland to convert Catholics; and even—illegally according to the laws of the land—to Morocco, to convert muslims. I also met and married a nice church woman and had a kid. All the while I was reading voraciously. Naturally I read the bible to pieces, but my courses at Roosevelt opened up the entire western tradition for me and got me doing research at the Newberry Library. In 2005 my Philosophy professor arranged for me to attend a graduate seminar on Montesquieu in the Committee on Social Thought, at the University of Chicago. Later that year I was accepted into the Literature track of an interdisciplinary PhD program called the Institute of Philosophic Studies, at the University of Dallas. Apparently I had some facility for scholarship and academic papers. I was winning awards and fellowships, and giving public talks on such topics as, “Sardonic Laughter in The Brothers Karamazov.” But I had this deep sense that what I was doing didn’t matter. Theory in the Humanities just doesn’t matter to me. Pedantry, fancy talk, arcane interpretations; I wanted none of that. And I didn’t want to write books about books. I wanted to write books about life. So I quit my academic studies in favor of more creative pursuits. I thought I’d finally solved the puzzle: I was not meant to be a photographer. I was not meant to be a scholar. I was meant to be a literary writer. I’d been hiding out in academe because I was afraid to put myself forward creatively.

But it’s hard to quit something you’re good at, even if you know it doesn’t matter. My wife and daughter and I moved back to Chicago from Texas in 2007, this time to Hyde Park. Fear hobbled me for another five years. Instead of throwing myself headlong into trying to publish poems and essays, I crept back into the scholarly world—again as an interloper in Social Thought. I got high on studying great books with world-renown hotshots in their fields. I studied Freud with Jonathan Lear. I studied Machiavelli with Nathan Tarcov. Rousseau with Heinrich Meier; et cetera. This was all profound stuff, and it felt important, but it still wasn’t essential to me. It wasn’t what I needed in order to develop myself as a human being. Studying modern poetry with Adam Zagajewski, however, was much closer to the mark. And in one of Adam’s courses I met the novelist Rosellen Brown. She was kind enough to meet with me over coffee to mentor me on the writing life. In 2012 I applied to two poetry MFA programs. Rosellen wrote letters of recommendation for me. I didn’t get in, but I didn’t care. I was happy to be overcoming my fear of rejection.

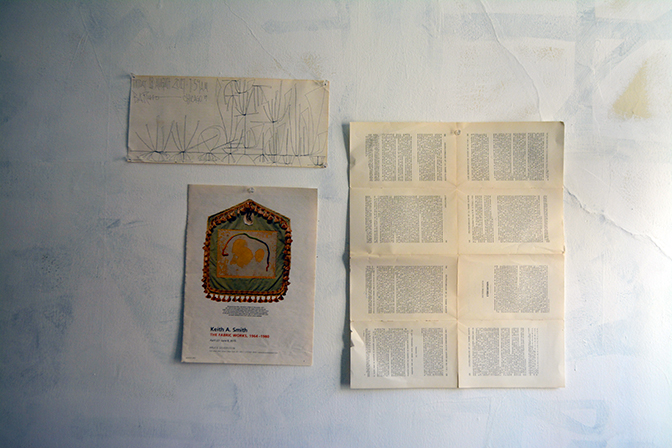

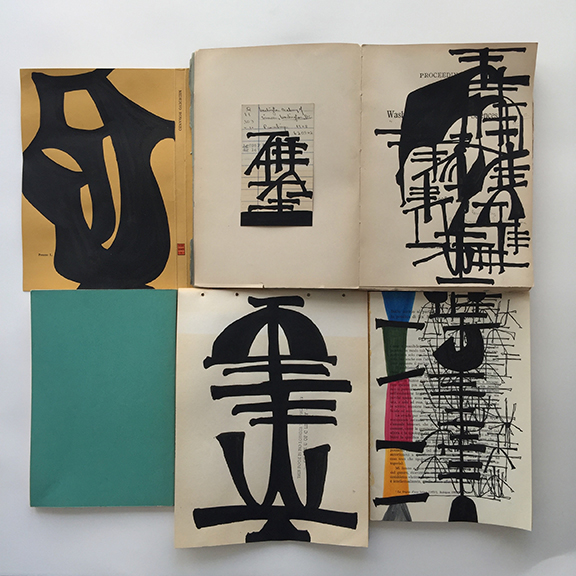

Finally I was writing and showing my work to great writers and no longer afraid of criticism. Yet something was still missing. I craved some sort of visual expression to complement my verbal efforts. I needed both. So I started making collages. And they were awful, just awful. I gravitated toward collage for the same reason that I first gravitated toward photography: because I was insecure about my inability to draw. I began to cook up a theory (always a bad sign!) about what collage is and why I was a collage artist. See I myself believed that an artist should be able to draw lifelike portraits and landscapes. And since I couldn’t do that, I needed some fig leaves to cover my nakedness. I did exactly what Nietzsche’s Zarathustra says you shouldn’t do: I muddied my waters to make them appear deep. But, what the hell; I was making art and having fun. I was getting closer to my true vocation.

Around five years ago you put more emphasis on developing a visual vocabulary. What initiated this shift? Also, are there any writers you frequently revisit? How does this interest intersect with your visual investigations?

October 2013 was a big month for me. It was one of those fertile periods, just chock-a-block with epiphanies and revelations. And October is always Chicago Artists’ Month, where the city goes crazy with art events and programming. So the time was ripe. Connected to that, the University of Chicago has this thing they call Humanities Day. So it’s October 2013, and I’m making all these bad collages out of book material because I love books and I’m trying to make an artist out of myself, and a tissue of inspiring events occurred. First I bumped into Theaster Gates at Powell’s, my favorite used bookstore. I worked up the courage to talk to him and we had a nice little chat about his then-current show at the Museum of Contemporary Art. The next day I attended an amazing talk by William Kentridge. He spoke to an audience of probably 1,000 people. That was my introduction to his work, and it prompted a bunch of new thinking in me about my own visual-verbal art aspirations. Just the fact that this world-famous artist was also making art on book pages probably gave me a sense of validation. Later in the month the University’s Department of Visual Arts offered a long tour of Midway Studios for Humanities Day. I attended a lecture by Amber Ginsburg, I looked inside Jessica Stockholder’s studio, etc. But the best thing came at the end. I waited until everyone was gone, and I accosted William Pope.L. He was patient with me. I gave him my crazy theory on collage and how I was a collage artist, and that, though I hadn’t known it previously, I now saw that I had to apply to the DoVA program for an MFA. I ended by asking him to give me one piece of solid advice. He actually took a moment to think about it and said something like this: One piece of advice? Don’t call yourself a collage artist. Just call yourself an artist. Don’t limit yourself. Don’t define yourself in any terms that keep you narrow or restricted. Be open; be free.

Now, Pope.L has no idea who I am or that I exist. And there’s no reason that he’d remember that conversation. But what he said absolutely changed my life. It was one of those great moments; one of those astounding, transformative moments. I did apply to the DoVA MFA program, and I did not get in. But I didn’t care. Once again, I was happy just to be evolving as a human being. Gaining the confidence to call myself an artist, to tell the world or anyone who would listen that I was an artist—that alone was a kind of coming-out-of-the-closet experience for me. It was wonderful. All that bullshit tough-guy stuff from my upbringing, or from the streets, or from blue-collar construction work, or from the Marine Corps (or even, in more oblique ways, from Christian evangelicalism and scholarly inquiry)—all of that finally breathed its last breath and I was free to identify myself as an artist and poet. By which I mean: free to be vulnerable, publicly.

So, I became an artist in October 2013, at thirty-six years old. Five years later, in October 2018, I made my first major sale, for $10,000, to a collector in New Mexico. It was a tremendous encouragement, and it came at just the right time. During the five years between my big declaration and my big sale, I worked like a demon. I taught myself how to be an artist by trying things out.

My favorite author is Michel de Montaigne. His great book is an 850-page tome called, simply, Essays. But in French the word essai means test or trial or try-out. It implies something experimental, provisional. It’s the opposite of dogmatic certainty. Montaigne’s famous motto is, What do I know? In his Essays, he essays his judgment on everything under the sun—thumbs, smells, sex, death, whatever. (He loves the great line out of Terence, that, Nothing human is alien to me.) I’ve read Montaigne’s big book four times, carefully. And every time I do, I start a fresh copy and mark up every page. I remember telling my wife that if I should die while our daughter was still young and stuck in the mists of childhood amnesia, she could give her my marked-up copies of Montaigne when she grows up, and she’d have a pretty good sense of who her father was.

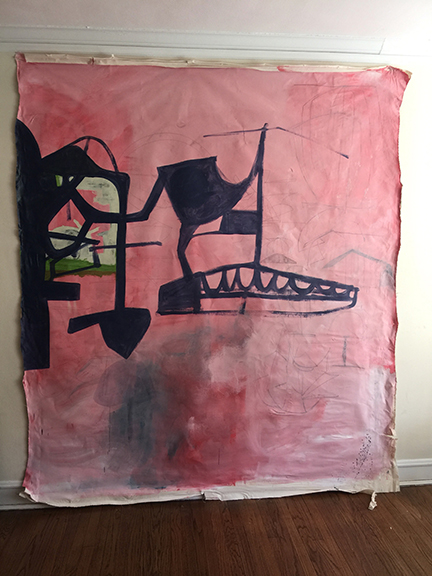

heavy muslin, 96″ x 84″, 2017

I haven’t read the Essays in about a decade. But it doesn’t matter: it’s in me; the book has tinctured me; I’ve metabolized it. Which influences the kind of artist that I am. I see myself as a visual essayist. I test; I explore; I try things out. I used to spend hours in my favorite art-supply store just ogling all the possibilities. I’d pepper the employees with questions and bring stuff home to experiment with. I learned by doing.

So I’m very much an intuitive, process-driven artist. I feel my way. I follow my nose. I respond to materials. I never know what I’m doing, but I do it anyway. E.M. Forster has this line where he asks, in his own voice, “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” In my case I’m always asking, How do I know who I am until I see what I make? Kierkegaard points out that it’s possible to look at a mirror without looking into it. Art-making, for me, creates a many-bevelled mirror to look into—a kind of mirror of the soul and for the soul. And what a privilege! You get to make stuff and catch glimpses of your inner world that you never knew were there. This is why I like to work quickly and spontaneously—to catch myself off-guard, unawares. A bad piece, or a failure, for me, is an emotionally dishonest piece. It’s one where I’m overthinking or hesitating or looking over my shoulder to see who’s watching so I can try to impress them. I don’t want to live like that.

Speaking of who’s watching, I initially encountered your work via Instagram. Though I prefer encountering art in person, social media has become a primary source for discovering new artists. Can you speak to how you use this format for disseminating your aesthetic practice?

Instagram is the only reason I have a smartphone. I knew immediately that I’d use the app only for art purposes. I never had any interest in broadcasting my family life or what I eat for lunch. It was only with great trepidation that I finally gave in and bought a phone at all. And, to be honest, I’m eager to get rid of it. I’d like to do an Instagram Live video one day where I throw the phone into Lake Michigan. Don’t get me wrong, in some ways it’s been wonderful. I’ve connected with marvelous artists from all over the world on Instagram. There is or can be a real community of mutual support there. As an artist I feel as though I’ve found my tribe through Instagram in terms of feeling affinities with various peers and betters that otherwise I’d never have known about. This has been especially important for me because I have no artist friends in my daily life, and no connections to an art school or any kind of art context. So it’s a lonely, isolated existence—another reason that books and art books are so special to me. But I’ve been on Instagram for four years now, and I’m ready for a break. I’ve gotten a good lay of the land and I’ve learned a great deal about who’s whom and what’s what in the contemporary scene. Now I’m ready to hunker down and work hard at a new phase of my art without the distractions of the phone. It’s hopeless, of course, and I’m quite stuck, but I do harbor this phone-free fantasy. The phone is a great thief of the poetry of moments. As for Instagram itself, well, it’s obviously going down in art history as a significant phenomenon.

What do you value most in your aesthetic investigations?

The great Maira Kalman says that all she’s about in her work is how to live and how to die. That’s all I’m about too. My passions are human self-knowledge and the conduct of life. I’m interested in preparing to die because I think that’s the way to live most fully. Really I think of myself as a philosophical moral psychologist who happens to be working in visual forms. Having forsworn all sophistry, I have no complicated theories about things. My artist statement is a simple way-of-life statement that I wrote in 2012. It’s a little poem of four gerunds titled, Note to Self:

let your making

be a playing

that is a giving

of your seeing.

That’s it. See, play, make, give. That’s what I’m all about. And that’s what I love most about the art life: it gives me a way to orient myself in the world. It gives me permission to be naïve. It gives me tools for exploring and tools for expressing. It combines a godlike power to create something out of nothing with a childlike sense of wonder and openness to experience. I mean, look, I’m forty-one. My life is half over. But I feel as though it’s just beginning. So there’s nothing like making art for the purposes of staying young! Certainly I’m at the beginning of my art career. I have much to learn and much to try out. There are many new things in me yearning to break free—from conceptual projects to large-scale cut-metal sculptures.

Currently you appear at a place where you are ready to exhibit works. I noticed a handful of series that appear to be at stage ripe for exhibition. Do you have any ideas about how you hope to call closure to some of your current projects? What else is on the agenda for 2019?

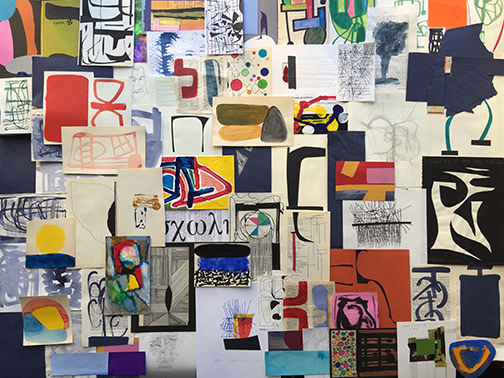

About a year ago I did this crazy thing. I noticed that the Renaissance Society had a two-week lull in their programming. I wrote to them and asked if I could swoop in and have a two-day pop-up show. “Just imagine it,” I said, “1 Artist, 2 Days, 582 Works of Art!” I wanted to cover the place salon-style, from floor to ceiling, with works on paper push-pinned to the walls. About a month later, when it was too late, I heard back from Karsten Lund, the Assistant Curator. And he said, bless his heart, something along the lines of, While we appreciated your bold proposal, we don’t get down like that. But how wonderful of him to have responded at all! I was delighted. And, you know, I have this new muscle in me where I’m not afraid of rejection. So I’ll just keep exercising it until I find a curator or gallery owner who’s equally adventurous and willing to take a chance on a no-name artist. But that’s what I’d like to do. I want to make a bold initial splash and have my first show be not only a solo show, but a kind of retrospective of my first five years of work. Because I really do feel like I’m moving into some new stage of work here at the beginning of 2019. And why not? Why not be bold? This is no time for me to be sheepish. It’s time to go for it. I’m ready.

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Brian Russo, please visit:

Brian Russo’s Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/see.play.make.give/

Brian Russo – http://www.see-play-make-give.org/

Artist interview, portrait, and studio views by Chester Alamo-Costello