In 2014 Chester Alamo-Costello started The COMP Magazine with a group of students (Egzon Shaqiri, Jessica Cuevas, Evan Griffin, and Jazzmyne Robbins) as a platform for covering new art and music in Chicagoland. In addition to functioning as the magazine’s publisher since inception, Chester has had an extensive career as an artist who documents and investigates a variety of contemporary issues that have come to illustrate how some of our city’s varied communities have intersected over the past 25+ years. This week The COMP Magazine caught up with Chester in his Printer’s Row home to discuss how he juggles seemingly unconnected activities simultaneously, his long running Art Drops series, the role Chicago has played in his documentary practice, and how all of this is translated into his teaching.

Though you spent portions of your youth in a number of places in the Midwest (Chicago, Detroit) and out east (New Jersey, NYC, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh), you grew up primarily on the south side of Indianapolis. Let’s step back and start with a look at the role the arts played in your youth?

Yes, I was raised on the south side of Indianapolis near Southport. Back in the 1970s this area was quickly being developed into new subdivisions. Our place sat on a dead-end street bookended by a couple plots of land that housed the last functioning horse stables. Though always holding down a job, my mother, Sharon, and stepfather, Terry, often struggled to make ends meet. Money was always tight. So, the arts were fairly absent. We lived in an old farmhouse where ‘art’ and decorations were of a rustic tone. The family room was panelled in weathered lumber one might find in a barn outfitted with old saw blades and pictures made out of painted scrap wood depicting Midwest landscapes and a large velvet painting of dogs playing poker. Some might say we were just one slope short of being full-fledge hillbillies. Probably what saved all of us were the bookshelves my mom filled with fiction, romance novels, sporting hero stories, and history books. She loved to read and shared this passion with us. All of this still seems so very ‘normal’.

I did spend time in a variety of cities visiting my father, Dennis, and stepmother, Liz, brother, Jeff, during summer breaks. My grandparents, Leo and Wanda, would load my brother, Matt, and me into their RV and shuttle us up or over to wherever. My grandfather would let us ride shotgun, track traffic reports and police activity on his CB radio. These excursions always felt like an adventure. When considering these trips now, I understand how much all of my grandparents valued keeping the family connected. This has always been important to me.

When my mother and stepfather found means we would camp in the hills of Kentucky or head down to southern Indiana to catch the Bill Monroe Bluegrass festival in Morgantown. I recall being introduced to local artisans who produced craft-oriented artworks out of leather and wood. Most of the items were utilitarian in nature, belts, vests, and walking canes. At that time, music was more important in terms of introducing me to the arts. Some of my earliest memories consist of us spread out in an open meadow, surrounded by bikers, carpenters, truckers with their families watching musicians play tunes like “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” and “Wildwood Flower” on banjos, dulcimers, fiddles, mandolins, and other vernacular instruments. It’s a bit funny to have these tunes still downloaded on my phone today. Looking at one’s youth over an extended period of time is ephemeral and intriguing, perceptions change with each revisit.

from the photobook Grandpa Danny, 2008.

You describe your art-making practice as a two-pronged approach. One method is embedded in a traditional documentary practice. While the other is define as experimental investigations. Can you expand upon this format of inquiry? How do you separate the two? Do you see this duality intersecting?

This duality can create a bit of confusion. Today, artists often build upon one aesthetic approach or style throughout their career. My methodology is sometimes difficult for some to align or fully understand my efforts with specificity. I do work in a two-pronged approach that I organise into documentary and experimental categories. I do see an overlap, but the mode does differ between the two. I prefer to take a highly objective point of view with the documentary work, while the experiments are clearly subjective. For instance, in the Artist’s Q&A’s and portrait work there is collaboration, but the end result is about the artist or musician. I do not want to distract from their voice. The experimental work addresses socio-political issues, is more conceptual, and the ideas that drive these investigations tend to poke at what is seen as ‘sensitive’ issues. Here, I use an interactive component where I engage random passersby in a manner that looks at the role of communication, trust, and the ephemerality of personal experience via the art-making process.

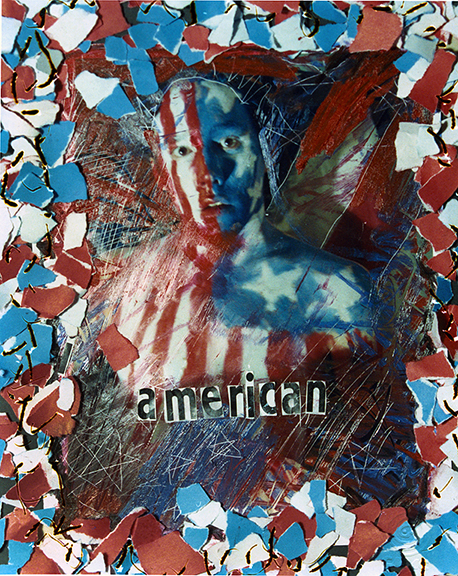

and Other Devices, 431 Gallery, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1992

Much of your experimental practice has involved creating artworks and performances that are designed to engage the general public in their environment. You have placed artworks for the casual passerby to find, keep, and respond to in numerous cities in the U.S. and abroad. Can you discuss how the art drops series began?

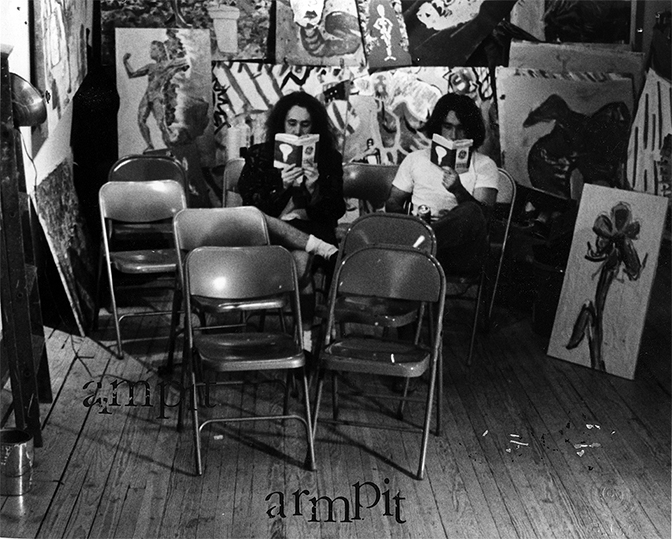

This work really stems from projects produced with Armpit: A Roving Street Gallery (1992-1998). Much of this performance group’s activities (art-walks, improvisational actions, urban totems) were produced specifically to engage people in the streets, along stretches of a country road or in vacant lots in urban neighborhoods often overlooked. We were looking at the Guerrilla Girls, Vito Acconci, Dada, the Viennese Actionists. In many respects, we were truly a ‘hot mess’, just all over the place. There was a lot of energy and spontaneity. Now, I see these experiences were really instrumental in forcing me out of my comfort zone. I still am in regular conversation with Jesse Bercowetz. We’re currently trying to pull all of this insanity into book form. The hope is using these early experiences in a format where we present the idea of failure as being a central component in making art. I think we both feel there is still unresolved business in need of tidying up.

“Searching for Geomantrick” (1998) was my initial solo series of this kind. I had been in the city long enough to realise that this was home, but I really did not know the city. So, I produced a series of 60 artworks that when assemble resembled a Chicago landscape. Each artwork (Geomantrick) was taken and placed in a city park for a random casual passerby to find, keep, and respond to. Around 22 years ago this month, I jumped on my bike and rode to 20 parks around the city, far south side, east, west, and up north, to make art drops. I think I received response from around 30% of the finders. I still have the notes in a binder from a Streetwise vendor, a business card from a CPD beat cop, and a host of others.

Why did you feel it necessary to expand the scope to include an international component?

I felt really engaged with this work. Though unpopular with my gallery, Lallak + Tom, at the time. I’m sure they thought why is this lunatic giving away his work. They were showing Joyce Tenneson, Joel-Peter Witkin, pretty traditional stuff, it wasn’t a good fit. I got dumped. I saw this as an opportunity for seeing other parts of the world. So, I decided to expand this investigation. The second series “Appleseed International” (1999-2004) and third, “New Street Agenda” (2005-2013) allowed me to expand these ideas further and visit places I had not been to in Europe, Central, and North America. Like the initial iteration, I tracked the finder responses and created a web archive. When looking at this work now, I find it interesting to compare how someone from Alaska or Florida can offer a similar response to someone from England, Holland, Italy, Scandinavia, etc. To date, I have placed artworks in roughly 60 cities in 20 different countries. I’m hoping to include Asia in the next cycle that will begin in 2021.

from the project Appleseed International, 2004

Your documentary practice centers upon activities and subcultures of Chicago. You frequently note the importance of participating with and understanding your immediate environment and subject. Why do you see Chicagoland a fertile locale for examination?

Chicago is a complex, diverse, fertile, yet troubled place. In some ways it’s a similar to L.A. and NYC due to being a port of entry and size. However, the attitude and economics are vastly different, and it is distinctively Midwestern. I’m interested in the city’s history, the visible differences found here in contrast to other American places, and the various cultural microcosms that are constantly changing. I’ve produced photojournalistic essays for newspapers and publications, but I prefer a more long-term approach. I photograph a range of topics, comics and gaming culture, artists and musicians, the street notes encountered in the public domain, and so on. I see all of these topics as extensions of myself through how I engage these communities.

Over a 5-year period I documented a Chicago sports pub in the North Center neighborhood where expats and Americans gather to watch football (soccer). This investigation culminated in the publishing of the photobook, The Globe, (2010). The design and pagination follows a football match (kick-off to penalties) through contrasting pictures made in this pub with drawings I produced, and essays by regulars that illustrates how this real life and virtual experience intersect.

Somewhere In-Between Chicago (2018) examines how my relationship with the city has evolved since I arrived in 1993. In this photobook are portraits of creatives and casual passersby interacting with the built and designed environment of Chicago, contrasted with imagery of the natural environment of the city that illustrates the seasonal changes. The book is divided into the four sections/seasons (spring, summer, autumn, and winter). As the book/year unfolds, the viewer is introduced to a range of viewpoints and life experiences, from young artists to established practitioners to evergreen stalwarts. The portraits are paired with imagery that reflects both the solidity and fluidity of the everchanging city that is Chicago. These visual materials are complimented by writings by Max King Cap, Juan Angel Chavez, Anya Davidson, and Paul Melvin Hopkin, and examine the impact of Chicago upon the creative process.

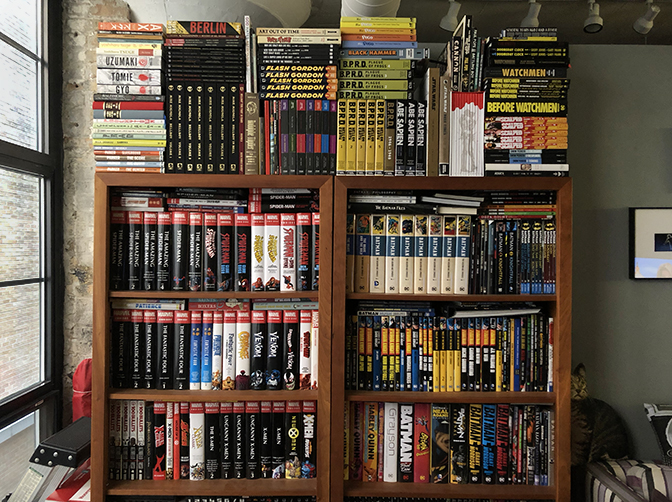

You are a bit of a bibliophile and collector. Can you discuss this interest? How do these pursuits inform your aesthetic practice and teaching?

I do have a bit of a collecting habit. This goes all the way back to collecting baseball cards and comics. My wife, Sandy, is a patient soul. Besides putting up with all of my other shortcomings, she allows me to fill our place with books, games, and toys. I’m highly organized, so, I’m consistently moving items in and out. Our home library is approaching 4,000 books. Initially it was art and photography books. In recent time my focus has expanded to include comics (artist’s editions, small press, omnibus), RPG gaming manuals (D&D, Pathfinder, Star Wars), and video game publications. I catalog each addition. I’m pretty obsessive about this.

I see collecting as rooted in the learning process. This habit educates me. I often share or give books to my students or pass on to my niece and nephews. When the pandemic began last spring, I used this as an opportunity to clear out books and items that I did not see myself rereading or using again. I made care packages and shipped out these to family and my students. I think this was more for me than the recipients. Purging is important in the building of a collection of any quality.

You have been at USF since 1999. In 2014, you started the COMP Magazine with students. Why did you initiate this effort? Can you describe the initial focus and how it has transformed over time?

Though USF is only roughly an hour south of the city I always found it difficult to introduce our students to contemporary art and music being made here. The COMP started primarily as a platform to introduce students to analysis and writing strategies. The arts coverage is really pretty slim when one considers the size of the city and the caliber of creatives who call Chicago home. There are some amazing talents who have a visible impact on current art and music dialogues. Yes, there’s been coverage in The COMP on well-known artists (Kerry James Marshall, David Bowie, Hairy Who, Andy Warhol), but I tend to be more interested with practices that often go unnoticed or work that is defined in the fringes. These investigations tend to feel more of this time and illustrate my interactions with Chicago.

I began doing the Q&A’s to highlight and introduce the students to various approaches by regional artists/musicians. Who and what is produced in the city is continually expanding. Since 2014, I’ve produced over 250 interviews and writings for the magazine. This effort has become a central part of my practice in recent time. Now, in addition to art and music, articles on comics and video games are being regularly presented. This evolution keeps the students engaged.

What are you currently working upon?

This has been an unusually productive time. I recently received an Illinois Arts Council grant to present the “Chicago Portrait Project”. This is scheduled for the fall of 2021. My hope is to show the project in the city at some point. In addition to the photographs, there are drawings, paintings, journals and videos.

Also, I’m in the design phase of my next book. This is going to be a collection of portraits made at the University of St. Francis contrasted with essays by alumni and others I have worked during my tenure. Since 2001, I have made roughly 600 portraits of students, faculty, and staff. The university is currently celebrating its centennial. Initially, the goal was to release this as part of the celebration. The situation has shifted due to circumstance. I’m now working with recent alumni and current design students on flushing out materials. The hope is to have the book ready for print in 2021.

Finally, there’s the Art Drops. This work has been in hibernation while I have been building up funding and developing a new series that will extend the previous iterations. The timeframe is dependent on how we respond to Covid-19. There is now a connection in China in place for next year. And, I am currently looking at options in Japan. On verra.

from the project New Street Agenda, 2005-2013.

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Chester Alamo-Costello, please visit:

Alamo-Costello Archive – https://www.alamo-costello.com/

431 Gallery Video – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QzRFlgXJ0-8

Chicago Arts Interview – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8tWLP0fxdEM

The Herald-News – https://www.theherald-news.com/2019/03/18/university-of-st-francis-art-professor-releases-book/aoczm5h/

Marina56 – https://marina56.com/portfolio/somewhere-in-between-chicago/

SI-BC Video – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ks0Dmv_FExY

Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chester_Alamo-Costello

Additional Documentary examples:

Rebecca Ono, and Brett Naucke), Chicago, Illinois, 2016

from the photobook, Grandpa Danny

Additional Experimental examples:

Interview by Kimball Cellcoost. Photography and portrait provided by the artist.