With nearly 40 years of collaborative efforts under their belts, Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman have expanded awareness of the female voice in the fine arts while simultaneously staying current with new formats and strategies for visual presentation. This week the COMP Magazine caught up with Ciurej & Lochman to discuss their experiences at the Institute of Design in the late 1970s, what has sustained their longterm collective investigations, what each values most in their aesthetic practice, and recent projects and artist’s books.

BC – Barbara Ciurej

LL – Lindsay Lochman

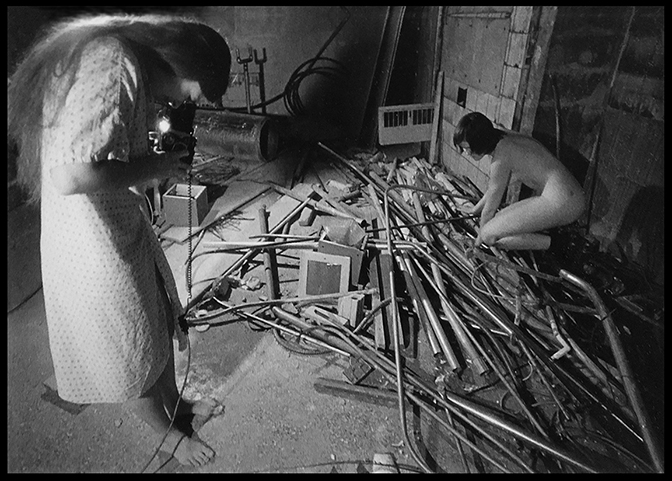

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Constructing Collaboration, 1977. Photo by Brian Franczyk

You have been collaborating since the 1980s. I believe you originally met while studying Visual Communications at the Institute of Design here in Chicago. Prior to this encounter, I’m wondering if there were any specific experiences or people that set you on your aesthetic journey?

LL – I grew up in a solitary space, looking at pictures or drawing them. I looked at my grandfather’s National Geographics, Chicago’s Field Museum dioramas and at the Saturday Evening Post. My Aunt Cordelia, a Kandinsky with needle and thread, was a great inspiration for me. I was under the impression that the Institute of Design would give me the skills to use my talents commercially. Instead, it focused my initial interest in fine art and history.

BC – My older brother had studied engineering at Illinois Institute of Technology, so when I read about the Institute of Design at IIT and its Bauhaus history, I thought it sounded interesting and applied. That turned out to be a fateful decision. I had always had a great relationship with my older sister and knew that the experiences we both understood were alien to my brothers. This shared female language became the basis of the work I did with Lindsay. I was disillusioned by the misogyny I witnessed in my Catholic upbringing and empowered by a cadre of commanding “home-maker” women relatives. Add in the political climate raging over reproductive choice and emerging equal rights for women – that was the brew I was steeped in.

What was the I.D. like during the time you were students? There is a rich history as was illustrated in the 2002 Art Institute of Chicago exhibition, “Taken by Design: Photographs from the Institute of Design, 1937-1971”. For instance, a number of former students (Joe Jachna, Ray Metzker, Lynn Sloan, Barbara Crane) went on teach and have a profound influence on generations of image-makers.

BC – The most illustrious photography teachers had moved on, but their legacy hung in the air. The Taken by Design exhibition which traced the history of the Institute of Design spanned 1937-1971. The school continued on but for us that particular modernist heyday was over and the energy was more diffuse. It was though people who moved on to teach elsewhere, were no longer in the fold and weren’t mentioned. Arthur Siegel was still teaching at the ID and upholding a demanding rigor, as were other lesser known teachers. It’s interesting to read in the Taken by Design catalog that one of Arthur’s catchphrases was: “Never force a camera on a woman.”

The eclectic mix of students supported each other and drew inspiration from the Bauhaus lineage of great theatrical parties. The spirit of experimentation and engagement with technical processes that flourished under Moholy-Nagy was still encouraged in the core curriculum, but advanced classes were painfully evolving into new models of Design Methodology. The photography department was a steady force in the turbulence as printmaking, film and drawing were phased out. The faculty and the legacy were male-dominated. There was only one woman teaching in the design program and Barbara Crane was the singular female graduate mentioned as noteworthy. During my final semester, Patty Carroll was hired in the photo department and was an important voice and encouraging role model.

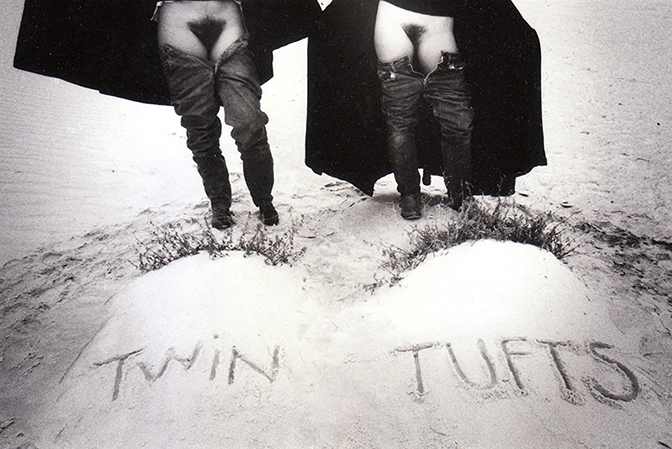

Lindsay and I were working separately and performing as protagonists in our own photographic narratives. The first collaborative project we did happened spontaneously on a road trip when we both arrived at the same visual conclusion. Working together was an organic process and generated a satisfying conspiratorial and subversive energy. We expanded on that energy, discovering the power of the pubic triangle to confront patriarchal fabrications. There was solidarity and catharsis in calling out male privilege and misogyny …our #metoo moment.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Twin Tufts, 1977, B&W silverprint, Chicago

Working collaboratively was not common and seemed to threaten some long-held notions. By sharing all aspects of image making from modeling to printing, we rejected the primacy of the individual artist’s vision, the inequality of the artist/model relationship, and the sole ownership of the image. We were interested in what happens collectively in making images.

Photographing performative narratives rooted in female experience and using humor, was an anomalous direction for ID students then, despite the fact that performance art and performative photography were burgeoning in the outside art world. Our teacher, documentary photographer and historian David Plowden, was so stymied by our project that he brought it to his wife to help him decipher what we were getting at. Fortunately, she told him to let us rip, and he did.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Perm, 1979, B&W silverprint, Chicago

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Mantle from Still Wet from the Cocoon, 1979, B&W silverprint, Chicago

LL – While the established order of the ID at that time provided us with an atmosphere inviting subversion, we did absorb its other influences. The school provided an excellent grounding in principals of design formalism and problem-solving. The creative energies of our cohorts fueled risk-taking and positive competition. Three-dimensional design professor, Elmer Ray Pearson, shared the lineage and history of the Bauhaus ethos. From him we learned the important relationship between studio practice and social practice. Ken Biasco provided an excellent grounding in learning to see. The fluid and mutable ways of storytelling were inspired by David Plowden, an instructor relentless in his demand for thoughtfulness and clarity. His insistence on “going half-way to engage the viewer” greatly influenced how we edited and contextualized the work. Patty Carroll provided encouragement and invaluable advice on maintaining an artistic practice beyond academe. Finally, we lauded Sylvia Smith, the unsung ID Administrator, who kept the place running and served as ballast on our intellectual voyage.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Cake Decorating from Still Wet from the Cocoon, 1979, B&W silverprint, Chicago

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Giving Her All from Still Wet from the Cocoon, 1979, B&W silverprint, Chicago

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Turkey Madonna from Glory on a Budget, 1980, B&W silverprint, Chicago

Having collaborated for over 30 years, your relationship and approach to materials and content has evolved. Are there any specific tenets that have been consistent since beginning to work together? What keeps the collaboration fresh?

LL – We have always proposed projects that come from our shared experience or our sense of outrage. We discuss, sometimes argue, and manage to find a direction that will accommodate the range of our individual thoughts. What’s fresh is that we are constantly challenged by how cultural myths have evolved and continue to change right before our eyes. In addition, each project requires a different technical/logistical approach creating another level of negotiation and thought.

BC –

My tenents:

Be open.

Suspend your ego.

Research. Question. Listen.

Keep a sense of humor.

Respect the dissenting view.

Trust the other person’s instincts.

Creative tension (a.k.a. arguing) is essential.

Marvel at where the work takes you.

What keeps this fresh? From the start, we shared an approach that considered the forces that shaped our lives to be subject matter. Our projects paralleled our lived experiences: coming of age, the quest to find a place in the world, existential questioning, the fraught world of fertility, childcare, nourishment, and now, advancing mortality. As we search for visual equivalents for these experiences, our working methods, formats and approaches evolve as we do, which keeps our collaboration interesting. The shifting political discourse continues to feed our work and has generated subject matter for 40 years.

Food is currently one focus in your practice. In recent projects, “Processed Views: Surveying the Industrial Landscape” and “Ponder Food as Love” you offer varied observations in how we consume, share, and think about nourishment as metaphor and subject on multiple levels, contemporary and historical. How do you see the present intersecting with the past when producing these series?

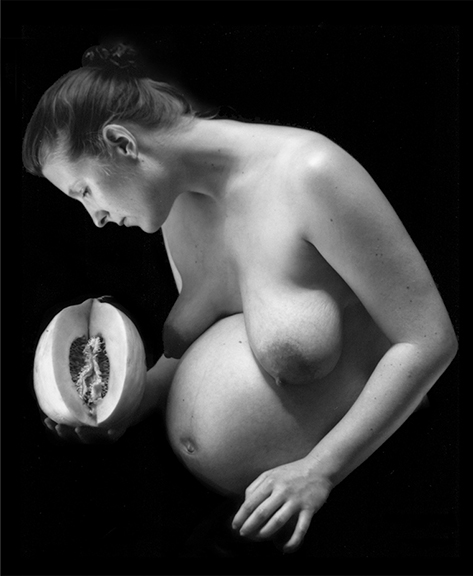

BC – We began to examine our own connection to nurturing our children in Ponder Food as Love and Playtime which telescoped into an interrogation of the agricultural-industrial complex that has overtaken our deep connection to the life-giving qualities of food.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Melon from The Creation Myth, 1995,

B&W silverprint, Milwaukee

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Fruit Roll Up from Playtime, 2010,

C-print, Milwaukee

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, little by little you’ve turned into fruit, Fig Heart from Food as Love, 2014, Archival pigment print, Milwaukee

In this work we reference the past in different ways – updating, debunking, building on it or using it as a cautionary tale. We observe historical changes shaping the cultural terrain. We research.

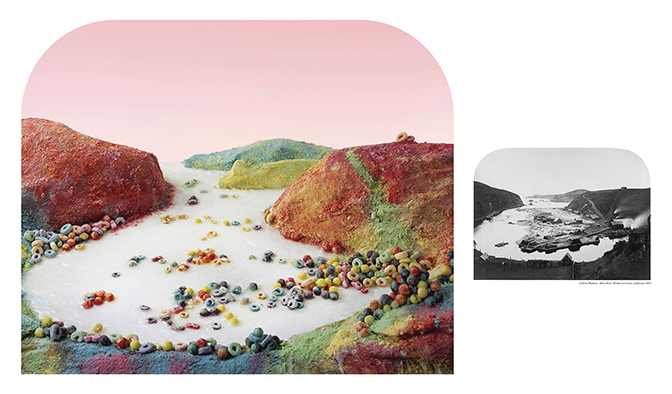

We incorporate our own memories.

For Processed Views, photo history and our interest in landscape imagery reminded the vast expanses of the American West. In the mid to late 19th century the frontier was marketed to settlers as a land of endless resources. One hundred fifty years later, we are seeing the detrimental environmental effects of our pursuit of Manifest Destiny, the philosophy that drove unconstrained territorial expansion. We still seem to be operating under this notion when it comes to our food systems. We considered the beckoning aisles of Cheetos, blue cupcakes and sugary cereals the contemporary landscape of food. We saw a parallel to that same unbridled expansionist impulse, as the processed food industry pushes further into new flavors and colors, leading Americans into uncharted dietary territory without concern for our health or natural resources.

The past does inform the present. We hope we can learn from it.

LL – Processed Views and the work we have done about food systems expresses our amazement at America’s historic love of commerce, its myths of progress and willingness to try anything because it is technologically possible. We weigh this drive with our nation’s befuddlement by the unintended, sometimes unfortunate, consequences of this marvelous drive and enthusiasm.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Fruit Loops Landscape with Watkins reference, 2014, Archival pigment print, Milwaukee

Lindsay, you teach at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee. Are there any specific approaches or ideas that you see as instrumental in sharing with your students?

LL –

You can’t know too much.

Your peers are your best teachers, take advantage of them. Show up and bear witness at their exhibitions.

Honor mistakes, they are indicators that work has been done and they allow opportunity for critical analysis.

Photography is like cooking. Pay attention, even when you experiment, if you want to make something nourishing.

Barbara, you are also a graphic designer. Do you see any overlap in this professional practice and your aesthetic investigations?

BC – For many years I considered design and photography separate, but dual – often dueling – careers, involving different parts of my brain. I invited a design client to one of our exhibitions and she remarked “Oh, I see, you organize visual information.” And, at the core, this is what these two paths share.

As photography moved from analog to digital, what I had once considered different skill sets converged. Additionally, I found my design skills to be invaluable for the demands of both production and promotion of the work. Within our collaboration, I am more likely to pronounce a project finished, accustomed as I am to working within client guidelines and deadlines, while Lindsay pushes to continue experimenting. We reign each other in with these opposing approaches and meet somewhere in the middle.

What do you value most in your artistic practice?

LL – Getting an idea executed and launching in the world to join the conversation is very rewarding. The process of doing this: inspiration, the process, the puzzle of presentation and occasional existential crisis is also satisfying – never a dull moment. I’m always learning new things from Barbara and from the work itself.

BC – Over the four decades that we have worked together, our projects became a receptacle of our shared stories. Our practice has been a way to reflect on and reflect back the tenor of the times we are living through. I am glad to have the language of photography to respond.

Collaborating has eclipsed other ways of working for me. It’s practical in providing cost-sharing, a road trip companion, a built-in editor, a willing model. In the presence of someone else’s skills, vision and curiosity, you are allowed to be more various. You learn about your strengths and weaknesses. They ask questions you never thought of. You cycle through questions in decades-long conversations which shapes the work.

What are the two of your currently working upon? Do you have any book projects set to release or upcoming exhibitions? What’s the plan for the remainder of 2018?

Processed Views: Surveying the Industrial Landscape is currently on exhibit at Granary Arts in Ephraim, Utah through September. The state of Utah leads the US in the consumption of Jell-O, so showing that work in the “Jell-O Belt” has particular resonance with our interests in American food mythology and systems. We are conjuring a hypothetical food migration timeline along the Oregon Trail, considering the adoption of processed foods as they come to define regional identity.

And in November, Enhanced Varieties will be on view at Revolve Project Space in Asheville, NC in Picturing Purity, an exhibition examining purity myths embedded in the language of environmentalism. It’s part of photo+sphere, a four-day art and science event with nationally known speakers, panelists, exhibitions, films, and performances, bringing attention to how we see our environment and the role humans play in determining the future of our planet. It’s been thrilling to have our work be part of these conversations.

photo+sphere – https://www.photoplusavl.com/about

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, Enhanced Varieties installation, 2018, at Granary Art Center, Ephraim, Utah

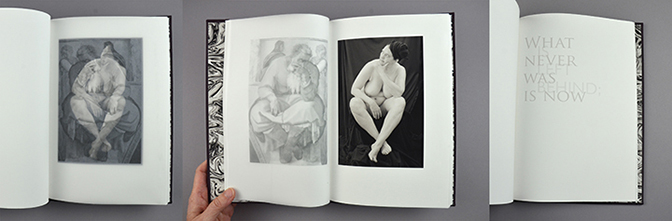

We finished a small edition artists’ book, Pliant History, and are launching it into the world, researching and evaluating appropriate venues. The project had its genesis ten years ago and took many forms before it evolved into this book. As we worked through the many iterations, it inspired another related body of work, Sibyls and Prophets, which we are developing. We are looking metaphorically at the ways power shifts form.

Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, artists’ book, Pliant History, 2017, digital piezography prints and vellum,

Chicago and Milwaukee

Meanwhile, we have been interviewing other collaborative teams for the online photography platform Lenscratch. It has been fascinating to examine the nature of other artistic collaborations and engage in a dialogue with these photographers. It has inspired a project where we are experimenting with another approach to collaborating for us – visual conversations weaving photos we take separately into experimental books.

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Barbara Ciurej & Lindsay Lochman, please visit:

Ciurej & Lochman – https://www.ciurejlochmanphoto.com/

Lens Culture – https://www.lensculture.com/ciurejandlochman

The Annenberg Space for Photography – https://www.annenbergphotospace.org/person/barbara-ciurej-and-lindsay-lochman/

Museum of Contemporary Photography – http://www.mocp.org/collection/mpp/past/lochman_ciurej_.php

Colorado Photographic Arts – https://cpacphoto.org/processed-views-barbara-ciurej-lindsay-lochman/

Candor Arts – http://www.candorarts.com/news/2018-pliant-history

Artist interview by Chester Alamo-Costello