Through a measured and thoughtful sophistication, Dan Devening has maintained a pivotal position in the Chicago art community (and beyond) for a number of years. Since arriving in the city in 1980, Devening has participated in seminal art exhibitions at top tier institutions and directed one of the city’s more progressive art galleries, devening projects + editions. The COMP Magazine recently visited Devening’s East Garfield Park studio to discuss the influences of early life experiences upon his current work, his role as an artist educator, the process of looking, and how and why visual information is sometimes arranged.

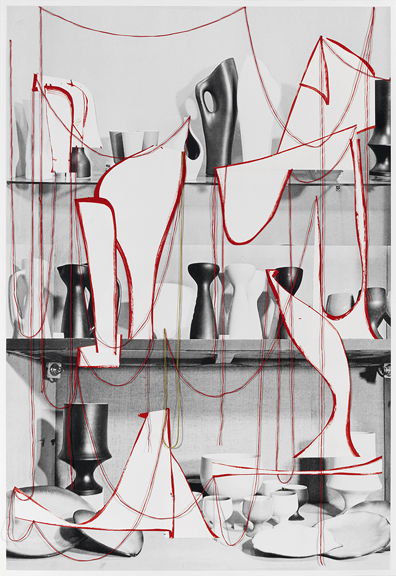

Dan Devening, Untitled, 2013, 40 × 32 inches,

archival pigment print, acrylic on paper, thread, tape

You’ve lived in a number of places (e.g., Nebraska, the Netherlands) while growing up. And, eventually settled in Chicago in the early 1980s. Can you share with us any specific early events that may have been informative in your artistic practice?

Hmmm, that’s a big question; I’ve been at it this long time.

I think I was an impressionable and curious kid who happened to be brought up in a military family. We were regularly on the move and stationed in several different places in the US and abroad; my exposure to varied cultures and languages was definitely an impactful part of my early life. When we were in Europe, I had access to places and experience that many other kids my age did not — museums, historical sites, etc. My sense of history and culture was certainly affected.

I received great support from my family and my teachers from the very start. My high school art teacher was a force; then when I went on to earn my BFA at the University of Nebraska at Omaha I was thrown in with a bunch of art kids who were hungry to make and experience new things. Working with professional teaching artists also opened my eyes to what it meant to be a productive creative person. I think I learned how to work and live by seeing my mentors navigate their own careers while teaching and raising families. My focus in undergrad was printmaking; one of the most significant aspects of that track was the visiting artist program tied to our department. We regularly invited nationally known visiting artists in to make prints. In the process of preparing the plates or stones, and then printing the editions, I watched real artists make their work. It became a kind of satellite studio for a very diverse collection of amazing people…and my fellow students and I were invited in.

In 1980, I went to grad school at UIC. That experience was a bit of a shock. I remember the first day of my first grad seminar. There were all these young people from different parts of the world all talking theory (what was that?). It was a very conceptually focused time in contemporary art and it seemed that all of our discussions were generated from debates about the validity of deconstructionism and/or post-modernism. It was great for me to be in the company of such a variety of cultural and ethnic experiences, intellectual backgrounds and artistic points of view. I think I chose well when it came to grad programs. Not only was the feedback from advising and critiques stimulating and challenging, as a state school, I was thrown in as a teaching assistant right at the start. The only difference was that I wasn’t assisting anyone, I was teaching my own classes the second semester of my two-year grad program. It meant that my poor students had as their professor, someone only a couple of years older than them…and probably only slightly more experienced. Right from the beginning, teaching studio art grabbed me. I’ve been teaching now for over 30 years and continue to be fed by the energy and imagination of my students.

Professionally, I’ve been very lucky. Over the years, I’ve been fortunate to be included in some important painting exhibitions with artists who I revere and respect. One of those was the Surfaces show at the Terra Museum curated by Judith Kirshner. The exhibition featured only 25 painters from Chicago so I was showing my work with Jim Nutt, Ed Paschke, Christina Ramberg, Jim Lutes and many more of my painting heroes. Since that show in the late 80s, I’ve put my work into richer and more challenging contexts — galleries, museums, project spaces — all of which offered me some new opportunity to recalibrate my work. I look forward to that continuing.

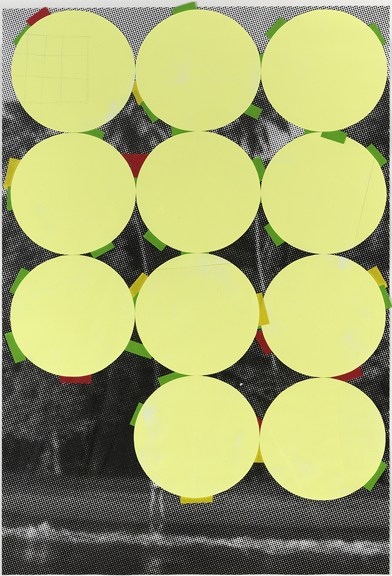

Dan Devening, Untitled, 2013, 36 × 24 inches,

Wilhelm Sasnal silk-screen print, acrylic on paper, tape

Your early investigations appear to be focused upon non-narrative visual strategies that employ high Modernist sensibilities. When I consider the various series Nets, Net Fragments, and Loops, Leaners, and Pools I see thoughtful attention and placement of formal elements like color, line, repetition, rhythm and texture. What is your fascination with abstraction? And, are there particular reasons for the elimination of representational items?

My painting — and the recent work with paper and installation — has always been a manifestation of how and why we look. Paintings are frontal and focus the perceptual experience within a particular set of parameters. Early on, I discovered interesting and conceptually useful links between painting and theater; the notion of a fixed encounter at an event that was authored, designed, staged and presented for the experience of the audience, fascinated me. Desire, expectation, surprise, visual cues are all manifestations of the fictions resulting from a staged narrative or within the framework of a painting. I’ve used curtains, scrims, nets and many other screening devices to disrupt, focus or draw attention to that perceptual encounter in order to trigger the self-awareness of looking. Although those concerns form the conceptual basis of my work, I would consider that only a part of the final work. The object, the plane, the surface, the material and the gesture are highly considered components driving my projects.

I’m not sure I would call my work abstract; maybe at times “non-objective,” but abstraction is so closely tied to the distillation of subject/image to some kind of essential form that I think my approach to image making is something more strategic. I think of myself as a visual arranger, a selector or placer of things within a particular context in order to elicit the most appropriate response. Maybe an agent of form might be a better or more high falutin title. I think that what I do is a form of abstraction; I’m not sure. I do think of myself as a formalist. Certainly someone who believes that “form carries meaning forward” and sees the material being of a thing as one of the most meaningful aspects of an artwork. I’m very focused on the final object and at times probably over articulate some of my ideas through the process. I’m working to break some of those habits in order to find a more immediate and expressive way of placing element within element. This need for a less constrictive means of working, has obviously driven many of the more recent collages. These are modest and investigatory pieces incorporating fragments and scraps from past works. With the stakes lowered here or with a more relaxed strategy in place, what results comes with a freedom that I’m quickly recognizing as very good for my practice.

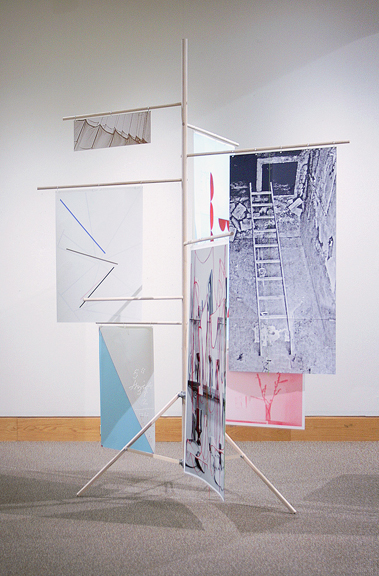

Dan Devening, Kiosk, 2014, Appx. 8′ x 5′,

archival pigment prints, collage, tape, thread, wood, hardware.

Can you tell us about your most recent solo show KIOSK (2014) at the Brainard Gallery, Tarble Arts Center at Eastern Illinois University?

The KIOSK project was inspired by the architect and designer Frederick Keisler’s interior design for Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery Art of this Century which opened in 1942. He made the presentation of the work, as much a concept as the art itself. With his system of displaying and disrupting the artworks presented in my mind, I constructed a simple floor-standing wooden tree-like device upon which works on paper were attached and hung like banners or flags. The arrangement occupied a central location in the gallery — like an urban kiosk — and you could walk around and into the work. The work was designed to be experienced from the front and the back. There was also some flutter created from air movement of people around the room and around the work. My main interest here was creating a display system that activated the viewer in a way a traditional two-dimensional work would not. There was an interest or desire to see the “other side” of something some curiosity and desire came into play. All of these elements are commonly used in retail display; that culture interests me as well.

KIOSK (the exhibition at the Tarble Arts Center) was a project that proposed a series of installation and wall works that played into how and why visual information is arranged and presented to an audience. There are very traditional and expected examples here — framed works on paper, prints, etc. — but even those are constructed to acknowledge the form used to carry over visual and conceptual information. Color, form, material and surface are the tools artists use to entice and activated the viewer; those are also some of my most important tools as well. How something is systematically designed, arranged and presented — both formally and conceptually — became the foundation for the installation. I was really pleased with the show; it fostered many new ideas about how the project might evolve and change.

William Conger, the esteemed Chicago painter and Northwestern professor emeritus wrote a beautiful essay for the small catalog that accompanied the show. It was a privilege to talk to Bill about the project and read his insightful response to this recent body of work. In so many ways, having Bill’s essay helped me understand more about what I was doing. Often it takes a fresh set of eyes to see what you’re really missing.

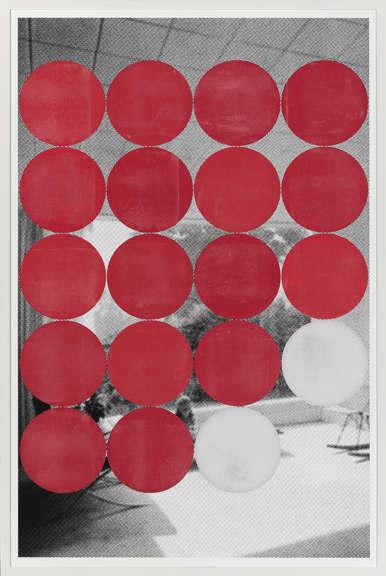

Dan Devening, Untitled, 2014, 41 × 32 inches,

archival pigment print, acrylic on paper, tape, frame

You are also Adjunct Professor of Painting and Drawing at SAIC. Do you see any connection between this endeavor and how you think about and produce work? Are there any philosophies or practices you regularly share with your students?

That’s also a huge question. Of course I dream that all of my personal and artistic values are carried over through my teaching, but who knows. Maybe. I know my teaching colleagues and peers work very hard to share their experiences, knowledge, insights and sense of criticality with their students; I’d like to count myself among them. I think I’m conscious that teaching is about using knowledge to impart new information and skills to one’s students; I do think a lot about what that knowledge is, its relevancy to those students and its relationship to broader cultural, historical and creative contexts. When I’m teaching painting, I often think about my own undergraduate painting instruction. My painting professor at that time was an amazing artist who spent almost all of his time talking about his son’s high school football team. He rarely gave demos or talked about our work. I remember my classmates and I pouring over books on painters to try to figure something out about what we were doing. It took me years to really understand my discipline; maybe that was his real subversive plan. Figure it out on your own! I think about that experience a lot; when I teach painting I know I’m sharing valuable technical, formal and perceptual information that will allow my students to more successfully communicate their ideas. At least I hope so.

With more advanced students, I think I bring a high degree of sensitivity to their projects. It can sometimes be difficult to talk about a young artist’s occasionally misplaced idea, but I’ve learned to respect those positions and bring what I can to help them clarify the work so that the work conveys what’s intended, evocatively and with ease. I think I’ve learned to be much more empathetic over the years. At times it can be a little too easy to impose one’s will on the work of a student; keeping their needs and desires before my own is something that must be kept in check…constantly. To accept and respect the work of one’s students is for me, the best way to generate the most interesting conversations and build a strong studio relationship.

Dan Devening, The London House, 2015, 60 × 40 inches,

archival pigment print; acrylic on plexiglas

The artwork The London House, 2015, piques my interest. This is a large archival pigment print with acrylic on plexiglass measuring 60 x 40 inches. 17 sizeable opaque red and 2 white circles obscure the view of what appears to be a black-and-white digital print of the interior of a mid 20th century modern home. I find the contrasting of these formal elements with architecture aligned with modernism to be clearly deliberate. Could this piece be considered a transitioning of your oeuvre?

The London House piece was a recent commission for the Chicago Four Season’s Hotel. The work plays into much of what I’ve done in my work in the past, but compresses the theatrical and fictive space into the framed space of the work. The dots are painted directly on the inside of the glazing; the print image sits some distance away mounted to the backing board and frame support. I saw this strategy as a way to activate the perceptual triggers that allow the viewer to see something clearly, while at the same time encounter of concealment. Much of what happens comes through how one fills in those covered areas of the print. I guess it’s about desire and frustration.

The piece also illustrates my deep love of 60s and 70s typography and design. The graphic elements on the glass connect with a period when high modernism found its way into popular culture through commercial design, super graphics, signage, etc. I like the boldness of the image and how it contrasts so strongly with the subtlety of the half-tone print. The piece seems to suggest two modes. One of those visual modes is assertive, declarative and lacking in subtlety. The other — a more hidden and secretive element — holds some mystery and gives the viewer a chance to dig deeper as they try to decode the clues in view. I look for the tension that results when two distinct components are forced to coexist; it’s at that point that things get really exciting for me.

Dan Devening, Untitled, 2013, 32 × 24 inches,

archival pigment print, acrylic on paper

Do you have upcoming exhibitions or plans for 2015-2016?

I’m showing some works on paper with galerie oqbo, a Berlin artist-run project, in Positions Berlin. This is a show corresponding with September’s Berlin Art Week.

I’m working on a solo show with a gallery in Wuppertal, Germany; dates for that project haven’t yet been set.

There are some new studio developments that I’m excited about. I have a series of paintings in the works that I hope to use to translate some of the concerns that have been driving the installation and paper works. We’ll see how that goes.

Dan Devening, Untitled, 2014, 17 × 13 inches,

acrylic on paper, collage

For additional information on the work of Dan Devening, please visit:

Dan Devening – http://dandevening.com

devening projects + editions – http://deveningprojects.com

oqbo – POSITIONS Berlin Art Fair – http://oqbo.de

Arts 21 Magazine – http://blog.art21.org/2011/01/25/center-field-multiple-possibilities-an-interview-with-dan-devening/#.VfF-FrQ-A_U

Dan Devening, artist and gallery director, Chicago, 2015

Interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello