Diego Rivera/Frida Kahlo in Detroit

Detroit Institute of Art

5200 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48202

March 15 – July 12, 2015

Detroit is a city that continues to rise from the ashes. This can be clearly seen in the bustling galleries at DIA, the massive renovations along Woodward Avenue, and the growing presence of the proud people that call the Motor City home in the Midtown neighborhood. Still dotted with numerous vacant buildings (including some beautiful mid 20th century high rises) and an underlying sense of budgetary and racial tension, Diego Rivera/Frida Kahlo in Detroit nevertheless marks a seminal juncture in the progress. Beyond a comprehensive look at Rivera and Kahlo’s tumultuous time in Detroit, the exhibition addresses aesthetic, economic, and political issues prevalent during the the Great Depression. There are uncanny parallels between the exhibition’s dialogues and materials to that of our present day America.

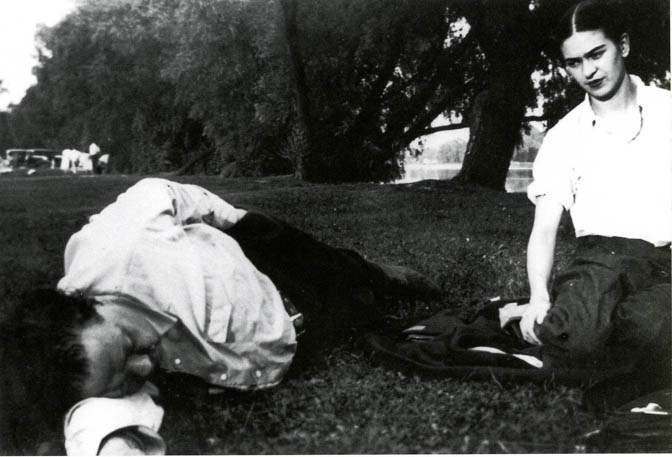

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, c. 1933, courtesy of DIA Archives

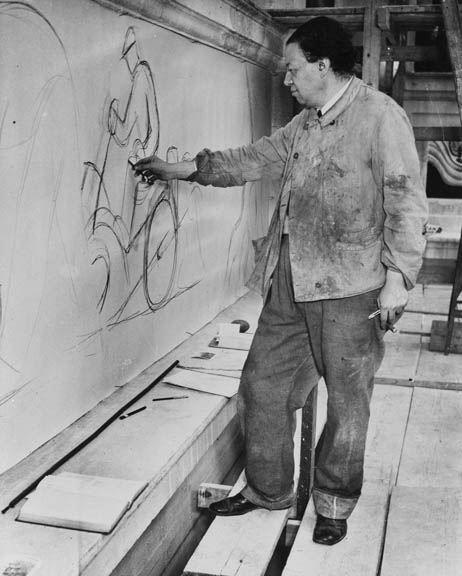

Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) are arguably the most influential and visible Mexican artists of their time. Each are represented in important collections and histories. Their lives and art have been highly mythologized via film, writing, and word-of-mouth. The focus of this exhibition is upon the creation of the permanent courtyard murals – Detroit Industry – produced between April 1932 and March 1933.

Frieda and Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, 1931, oil on canvas, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, Gift of Albert M. Bender © 2014 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Rivera, over 20 years senior to Kahlo, was an established muralist having produced large public works in Mexico and California when he was approached by Wilhelm R. Valentiner, DIA Director in the 1930s, to produce the expansive mural. Though there was criticism for this selection (many felt Rivera’s affinity with Communism to be detrimental), Valentiner found support in American industrialist, Edsel B. Ford. One of America’s wealthiest, Ford saw this gesture as a means to alleviate tensions due to overwhelming unemployment in the region. Sadly, on March 7, 1932, shortly before the arrival of Rivera and Kahlo, the Ford Hunger March took a turn for the worst when over 60 marchers were injured, including 4 fatally (a 5th would succumb to his wounds 3 months later), due to gunfire procured by the Dearborn Police and Ford Security Guards. It has been noted that this incident was a key event in the unionization of the U.S. auto industry.

Exhibition View of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, Courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Art

Kahlo’s diaristic self-portraits are present. Often dressed in indigenous Mexican attire, Kahlo is seen as exotic when juxtaposed to an assortment of fauna and foliage. Here, her portraits frequently allude to a romantic sensibility one may associate with a simpler way of life. There is a naïve sensual invitation in her skillful handling of narrative on par with the greatest of outsider artists. However, the explicit (and most powerful) imagery addresses the loss of her still-born child at this time cannot be overlooked. Having arrived to the states pregnant, Kahlo struggled with her pregnancy both emotionally and physically. Having endured a near fatal bus accident in 1925, carrying child through full-term was only a marginal possibility due to a previously broken pelvis and piercing of the uterus by iron handrail in the accident. In the sketches and painting, Henry Ford Hospital, 1932, one sees the anguish of this loss. Kahlo’s fatigued naked body lies limp upon hospital bed with yarn-like tendrils extended above and below her body attached to fetus, pelvic bone, snail, flower and man-made items in a barren industrial wasteland.

Exhibition View of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, Courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Art

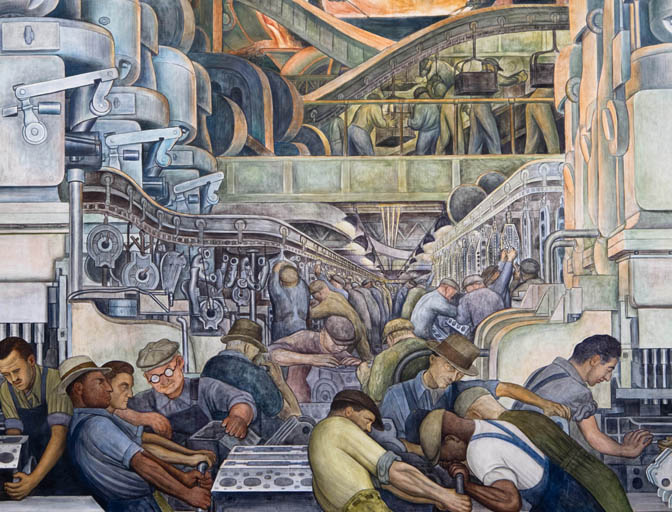

The exhibition is also a celebration of humanity and innovation. Rivera was fascinated by American industry. He took this queue as a means for fully immersing himself (and politics) into the murals. Seeing the to-scale cartoons, photographs of the process, and archival film footage illustrates a fervent period of work and play. Rivera, the clever symbolist, placed messages throughout the mural. For instance, Rivera addressed race through including people of color working alongside whites. This was not common due to strict segregation.

Detroit Industry, north wall (detail), Diego Rivera, 1932. Detroit Institute of Art

One may wander what Rivera and Kahlo would think of Detroit today. At times, the city has become a symbol of the chasm that divides the wealthy from the down-trodden. The Rivera murals were once defined as being “vulgar” and “un-american” by The Detroit News, and some sought to permanently destroy these master-works. Thankfully this action was curtailed. This myopic (and hateful) referencing is in antithesis to what Detroit (and America) have become. This exhibition reflects the ongoing evolution of a city (and transformative country) that continues to define itself through diversity, innovation, and seeking communal dialogue.

Additional images from Diego Rivera/Frida Kahlo in Detroit:

Exhibition View of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit, Courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Art

Diego Rivera drawing – on scaffold, Courtesy of DIA Archives

Frida Kahlo on balcony above Detroit Industry Murals, courtesy of DIA Archives

Rivera and Kahlo on Belle Isle, courtesy of DIA Archives

An Endnote:

After 16 years of directing DIA, Graham W.J. Beal will retire as of June 30, 2015. In this swan song, Beal ends his tenure overseeing one of the most interesting museum exhibitions of 2015. Beal has guided DIA through troubled waters (including maintaining a collection in full) with an acumen that signals a fresh vitality for one of America’s truly important art collections.

For additional information on the exhibition and the work of Rivera and Kahlo, please visit:

Detroit Institute of Art – http://www.dia.org/

Diego Rivera Foundation – http://www.diego-rivera-foundation.org/

Frida Kahlo Foundation – http://www.frida-kahlo-foundation.org/biography.html

Review by Chester Alamo-Costello