Hairy Who? 1966–1969

September 26, 2018 through January 6, 2019

The Art Institute of Chicago

111 South Michigan Avenue

Chicago, IL 60603

Galleries 124–27 and 268–73

Late to the show, this writing has been difficult to find fruition. The Hairy Who? 1966–1969 at the Art Institute of Chicago felt a bit dated, possibly due to my focus on Chicago’s current aesthetic investigations or long familiarity with these materials. I was most drawn to the content in the Drawing Galleries due to the intimacy felt. The scale and focus upon artworks vs. space tends to suit the candid content presented. This is not to say these works are modest or this effort does not hold importance. The aggregation on display is organized adequately in two galleries. Karl Wirsum, Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, Art Green, Jim Falconer, and Suellen Rocca are truly important artists in the canon of art produced in Chicago, and beyond. Yes, beyond, for this group set a foundation that resonates in so much of what continues to be key to visual art production and presentation here in Chicago. Their impact can be divisive and heartwarming simultaneously in conversation 50 years on.

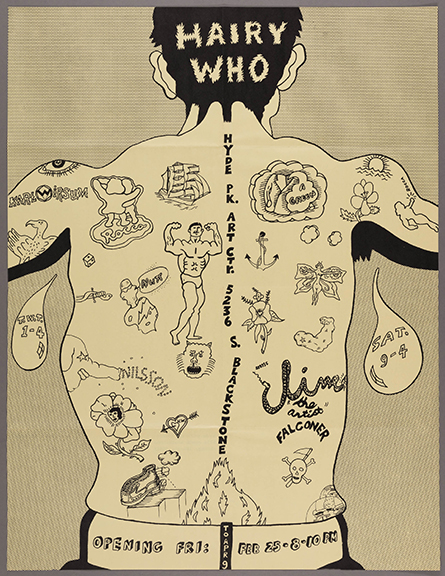

Jim Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum.

Hairy Who, 1966. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt.

Landing in Chicago in 1993 once again, I had little understanding of the complex rawness of the city or the history of art produced here. Nor was I familiar with Chicago’s relationship to larger international art dialogues. Over time I became aware that there has been clear animosity in response to why artists producing art here have often gone mostly unnoticed. This can be attributed to a number of items that appear to be under remedy. Some have cited the lack of a serious art publication for extended periods of time, minimal coverage by local media, and nominal support from area institutions and collectors comes up in conversation and has been written upon. Nevertheless, great art has regularly been produced here. This matter is fairly apparent today as area artists become more visible due to, in part, advancements in our digital age.

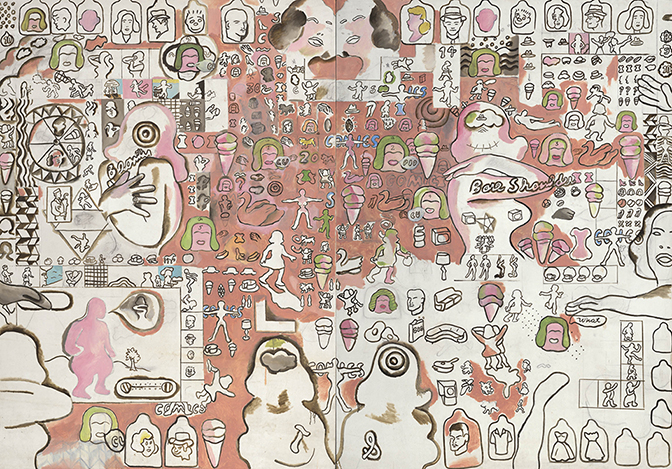

Suellen Rocca. Bare Shouldered Beauty and the Pink Creature, 1965. The Art Institute of Chicago,

Frederick W. Renshaw Acquisition and Carol Rosenthal-Groeling Purchase funds. © Suellen Rocca.

The period of time and age of the artists piqued my interest initially. Most in their early 20s had the uncanny foresight to organize into collective focus and exhibit as a group 6 times during an instance that coincided with a period of tumultuous American history not dissimilar to our own. Supported by Don Baum, exhibition Chairman at the Hyde Park Art Center, history was written. Synchronicity ensued due to Baum’s backing and their proactive approach with exhibitions at the San Francisco Art Institute, the School of Visual Arts in New York, and the Corcoran Gallery at Dupont Center in Washington, D.C. Through these exhibitions they were defined as a cohesive unit even with clearly disparate interests and concerns under investigation. This solidarity contrasted with distinct visual styles and narratives is not uncommon in the heartland, a place that is essentially a converging point of east and west sensibilities. This acumen can be seen in the exhibit.

Art Green. Consider the Options, Examine the Facts, Apply the Logic (originally titled The Undeniable Logician), 1965. Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, Anonymous Gift. © Art Green.

At the crossroads there appears need to classify and define their output in relationship to other art movements, their predecessors, and stewards. It has been documented extensively by art critics (Dennis Adrian, Lawrence Alloway, Whitney Halstead) that the Hairy Who holds an affinity, yet diverges away from Pop Art due to the time of production, place, and personal experience. Chicago in the 1960s was gritty, like New York, yet dissimilar in terms of association. Pop Art paralleled Minimalism while the Hairy Who was informed by the Monster Roster (Cosmo Campoli, Dominick Di Meo, Leon Golub, June Leaf, Nancy Spero, and Seymour Rosofsky). This precursor coupled with the idiosyncratic visual culture, volatile political environment, and DIY mentality set a tone for rebellious behavior that still thrives in the city today. One can only take a tour of today’s artist’s studios and exhibition spaces that pop up, survive for a short period of time, and produce amazing visual experiences in remote warehouses, single bedroom apartments, and storefronts in off the beaten path neighborhoods to understand there is empirical difference.

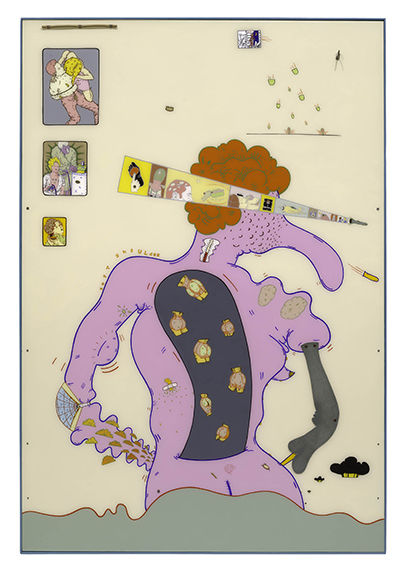

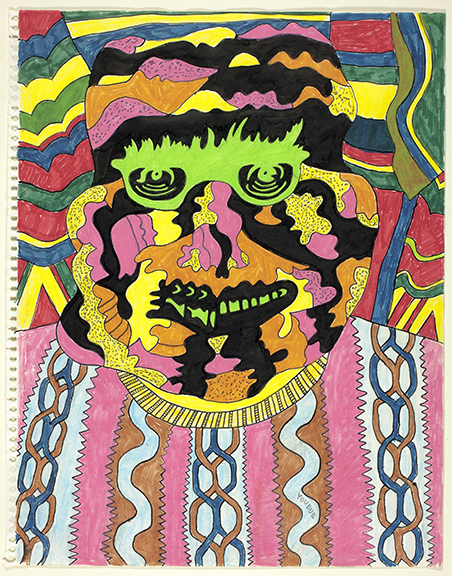

Jim Nutt. Miss E. Knows, 1967. The Art Institute of Chicago,

Twentieth-Century Purchase Fund. © Jim Nutt.

Chicago artists have held a fondness for ‘jolie laide’ aesthetics as seen in French culture and film for some time. In selecting materials and subject matter that is more aligned with back-alley tarot mystics or tattoo parlors circumvents pre-described definitions of beauty. In looking at Jim Nutt’s Miss E. Knows (1967) one encounters the back-view of a monstrous pink torso and head, complete with a jutting penis for a nose and razor sharp breast. The painting alludes to a comic’s inspired narrative due to the three panels in the upper left, interspersed iconography, yet an abstract and allusive interpretation can only be culled. This work, like many presented, raise many questions, yet require the viewer to take charge in locating interpretation. Though initially opaque, this approach is intended. Nutt, like his peers, want you to take pause, reflect and pull meaning from the experience. Like life and Chicago, they’re not going to hold your hand through this tour.

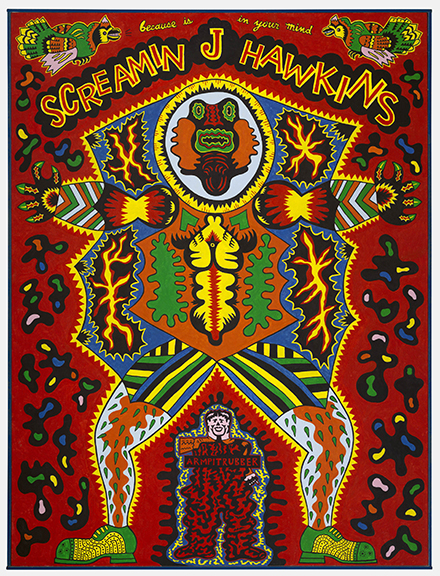

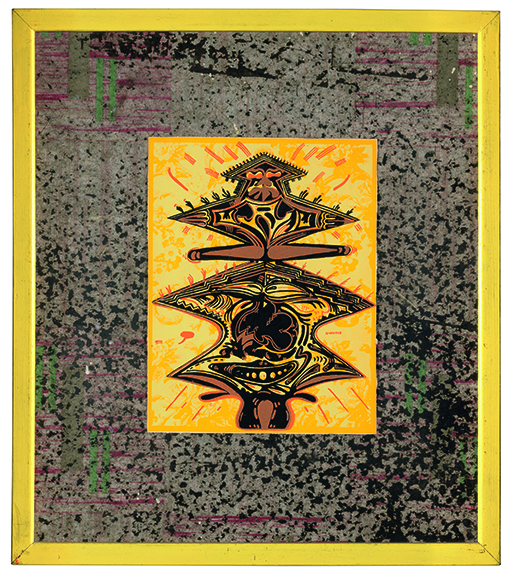

Karl Wirsum. Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, 1968. The Art Institute of Chicago,

Mr. and Mrs. Frank G. Logan Purchase Prize Fund. © Karl Wirsum.

Karl Wirsum’s Screamin’ Jay Hawkins (1968) is a masterwork. The symmetry and vibrant color palette exudes a queerness that becomes even more pronounced through the odd green and yellow shoes and curious birds that frame the scene. There is a weird funk magic present in this painting that mirrors the musician’s mystic style. Hawkins penned the classic R&B ballad ‘I Put a Spell On You’ in 1956. It’s noted in the AllMusic Guide to the Blues, that the entire band was intoxicated during a recording session where “Hawkins screamed, grunted, and gurgled his way through the tune with utter drunken abandon.” In 2014 I visited and made a portrait of Wirsum at his home and studio. From floor to ceiling was a massive collection of vintage toys and art by outsider artists and peers. The environment and Wirsum were full of energy and this is central to the voice conveyed in this painting.

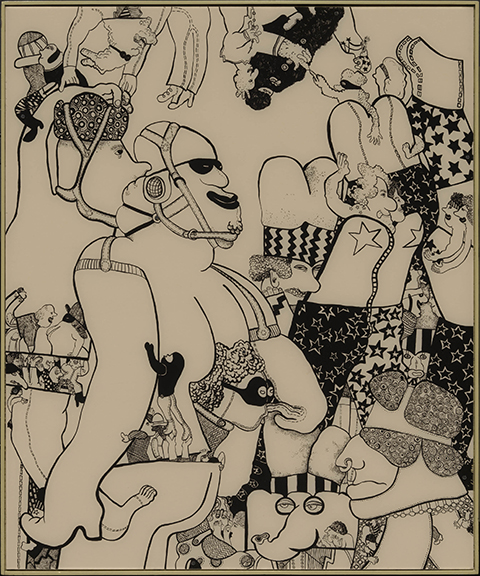

Gladys Nilsson. The Trogens, 1967. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago. © Gladys Nilsson.

I believe the first time I encountered the work of Gladys Nilsson was at the Printworks Gallery in River North in the mid 1990s. I was mesmerized. The works reminded of the merging of static semblance encountered in the psychedelic art of the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine (1968) meshing with clean-line abstraction and trompe-l’œil image play. The Trogens (1967) is refreshing to see on view. Painted on Plexiglas, a common material of the Hairy Who, Nilsson procures a 2D-dimensional space for the viewer to wander within. The depth one immerses oneself into is dependent upon the willingness to explore the hidden realities culled through inspection. The deeper one looks, the more one finds, be it phantasmic forms, multiverse phenomenon, or inquisitive iconography drawn from youthful experience.

Jim Falconer. Untitled, 1968. Collection of John Pitman Weber. © Jim Falconer.

The exhibition, The Hairy Who? 1966-1969, is AIC’s affirmation of this important art collective that has informed Chicago artists and an audiences for 50 odd years. The task now is to continue to build upon the momentum created by these trailblazers and continue to reach beyond local terrain. There’s been an imponderable peculiarity that has defined the existence and practice of creatives that makes up the perspicacity for those unfamiliar with life in the Windy City. And, at times, substantial art is produced here. This exhibition and the current output by many artists brings light to worthy voice and visuals that will hopefully require further reflection. These Chicago artistic predecessors and the city deserve nothing less.

Karl Wirsum. Youdue, c. 1966. The Art Institute of Chicago,

restricted gift of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel W. Koffler. © Karl Wirsum.

For additional information on the Hairy Who and publications, please visit:

The Art Institute of Chicago, Hairy Who? 1966-1969 – https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/2722/hairy-who-1966-1969

Dan Nadal, The Collected Hairy Who Publications 1966-1969 – http://www.artbook.com/9781880146965.html

Thea Liberty Nichols et al, Hairy Who? 1966-1969 –

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300236903/hairy-who-1966-1969

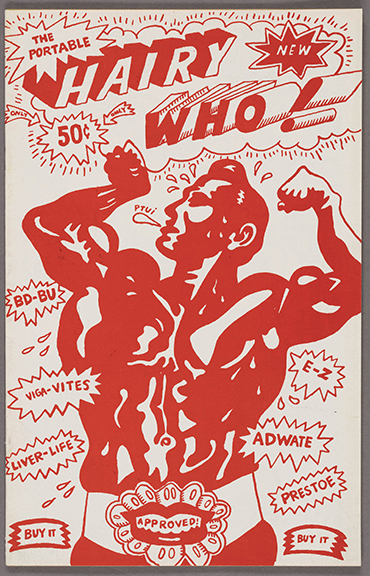

Jim Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum. The Portable Hairy Who!, 1966. The Art Institute of Chicago,

gift of Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt.

Review by Chester Alamo-Costello