Working through a transitional period in recent years, Heather Mekkelson has found solid footing in raising a family while investigating new modes of looking at and translating contemporary aesthetic perceptions as they relate to empirical and speculative sciences: anthropology, astrophysics, cosmology, myth, and mysticism. This week the COMP Magazine headed up to Logan Square to discuss with Mekkelson how she balances parenting and working in the studio, her attention to color, the relational process in material selection, and how the arts and sciences intersect in her practice.

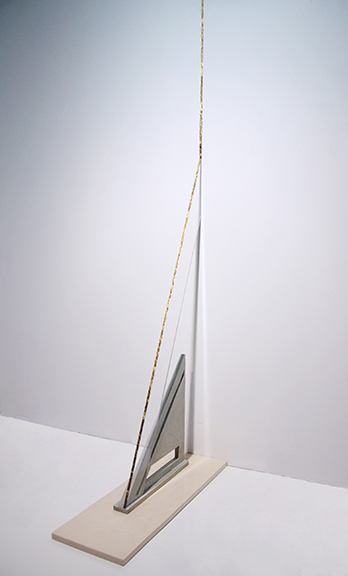

Heather Mekkelson, There Is No Fixed Place, 2017, brass, bismuth, acrylic, mirror, glass, polyester yarn, steel, 15x9x42” with variable elements, 65GRAND, Chicago, Illinois

Can we start with formative experience? You were born in New York and have lived in a number of locations out east and in the Midwest. Are there any specific early experiences or persons who you see as having an impact in prompting your aesthetic investigations?

That’s true, we were on the move for most of my childhood. In spite of the constant relocation, I was a happy kid—a dreamer, and definitely comfortable being alone in my own company. As I got older the moving around became harder. I found solace in my teenage years walling myself up in my room and drawing. Around this time in high school I was lucky to take my first art history class. The stories surrounding the work that Carol Shumate, the teacher, would tell were completely absorbing. She put every work we looked at into a social, historical, or religious context in a totally fascinating way. For a sixteen or seventeen year old kid to learn that for every time and place, deep into our world history, there was an artist responding—it awoke a deep appreciation in me for artists and their pursuits. That was the first time content, context, and concept became inseparably linked to art for me. It was also my first exposure to modern and contemporary work.

Still, I couldn’t visualize life as an artist, as much as it was pulling at me. I struggled for some time with career ideas that could combine art with a science field, since a natural science was something I always thought I would pursue. It wasn’t until a few years after I transferred to the School of The Art Institute from Purdue University that I came to see that a professional studio practice could encompass all of my interests, whatever they may be.

Heather Mekkelson, Direction Moved, 2014, MDF, latex paint, tape, acrylic, first surface mirror,

16x16x16”, 65GRAND, Chicago, Illinois

You and David Roman have a daughter. As an artist and mother, I am wandering how this impacts your art practice? Did you see any shifts in how you think about and produce work upon this introduction in your life?

I see it in these terms: life changes, people change, and as an artist, your work follows. I was out of grad school (UIC, ’08) for a short while when our daughter was born. Between her arrival, working on a huge job, and rehabbing our new house, my studio work took a back seat for what felt like a dark eternity. It was actually less than a year, but time is a fog when you’re a new parent. I was already tailing off my last body of work that I was involved with since grad school, searching for a new direction. When I got my studio time back, my basic desire was to dive into something that would entertain and challenge my faculties…Work that I could respond to immediately instead of getting tied down in a proposal process.

I was once given some advice from my grad school advisor, Rodney Carswell, to “find your model”, meaning look around you for examples of the artist you want to be. When I would look at work by artists I admired, I could feel a quality in it that expressed how much they truly enjoyed making their work—it was palpable in their creations. It had been a while since I felt that, and if you’re not feeling it, the work suffers. From that moment, I freed myself from compartmentalizing what is art material and what is the baser material from the muck of life, and gave myself carte blanche to use whatever I wanted to make the connections I saw.

Heather Mekkelson, Missing Things I’ve Never Known, 2017,

glass, cement, ink, wax, epoxy, enameled MDF,

18x27x45”, 65GRAND, Chicago, Illinois

In the series “What It Is We’re Measuring”, 2017, at 65GRAND, you work with a variety of materials and ideas. At core these are sculptural works that invoke pause and contemplation. Can you discuss the applied and conceptual process of the creation of this series?

I approach making work as an exploratory process—as if I’ll be able to brush upon some truth, or at the very least, illustrate the question. Part of that change in path I was just describing, was embracing this reverence I have for unanswerable questions about life and the fields of inquiry that tackle them. Some of those fields, among the many, include astrophysics, cosmology, cosmogony and myths, geology, anthropology, even pseudo-science and mysticism. Thinking about these subjects so far beyond my reach and relating them back to the trivialities of my personal life is a humbling, entertaining method to cope with the madness.

Here’s what I chew on: Time feels stubbornly linear and concrete but it isn’t whatsoever. Deep space is possibly comprehensible if I picture it as an ocean, but that fails to express its material, or lack of it, not to mention its expanse. Communication, consciousness, technology, all of these fundamental human structures that we assume are ours to control, are wrought with inherent limitations. I believe it comes down to a “sampling problem” wherein we operate from an extremely limited set of faculties. I walk through life looking through the lens of my own narrow perception, assuming that’s truth, like we all do.

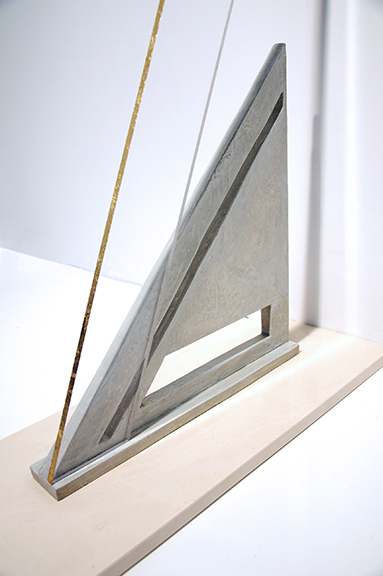

Heather Mekkelson, Crepuscular Beam, 2016-2017,

acrylic, gold leaf, wood, modified plaster, wax, pigment, travertine,

28×10” x height variable, 65GRAND, Chicago, Illinois

What I wanted to do with the work in “What It Is We’re Measuring” is bring an awareness of perception to the forefront. Back in 2015 in “Now Slices” (65GRAND), I showed a piece called Direction Moved (2014) that I feel paved the way to last year’s work. I had a white box with yellow tape in the studio as a stand-in base hanging around. A small block of lucite and a first surface mirror were sitting on the box, just to stay clean and out of the way, when I noticed the perceptual effect of the arrows appear as I moved around it. The combination of items haphazardly placed together created this pointed, but absurd illustration of the general theory of relativity, which I had been grasping at. The permanent version of the sculpture uses a replica of the box for its base.

Missing Things I’ve Never Known (2017) approaches perception in a similarly physical way, shifting in appearance as the viewing position changes. Two horizontal paths of glass tiles are propped up on concrete casts from toy packaging and paper snack cups—scraps from everyday life. The tile paths stand as my simplified model of “Now Slices”, or “Time Slices”. These are theories I keep returning to that describe all of time as being simultaneous and the neurological limits of perception. The individual paths narrowly miss one another and continue on. It’s an homage to everything we miss in life and the parallel lives we’re not living.

All of the works in that show presented different ways of addressing perception and awareness, but one last example I’ll share is Crepuscular Beam (2016-17). It takes its title from the strong shaft of sunlight that occurs through objects like clouds or trees at a dawn or dusk twilight. Conditions must align just-so to cause their appearance; the air must have a relatively high particle saturation, a contrast of dark objects must be adjacent to the light, and the earlier or later time of day is necessary for the light to pass through forty times as much atmosphere than at midday. There is a geometrical formula that can be used to describe how this all occurs. Yet more than any other condition, the most integral factor in this optical phenomenon is your perspective and position in time. The thing that gets me, is that it’s not so terribly rare.

Heather Mekkelson, Crepuscular Beam (detail), 2016-2017,

acrylic, gold leaf, wood, modified plaster, wax, pigment, travertine,

28×10” x height variable, 65GRAND, Chicago, Illinois

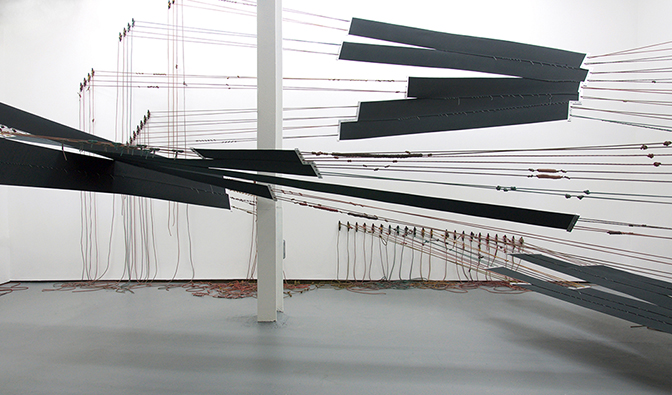

I see specificity in your attention to color. For instance, opaque black bands are suspended by strands of rope that are muted in the installation “In Absentia Luci” (2017, 4th Ward Project Space). What role does color selection play in conveying your idea?

Color is used wherever it is a deliberate part of the subject. In the 4th Ward Project Space installation, In Absentia Luci, (2017) the black elastic orthogonal elements acted as spatial brushstrokes that simultaneously point to deep space and the planes that bisect the sky space over my back yard—the result of overhanging wires. The sequentially-knotted paracords were all toned to the specific hue of mauve seen in Chicago’s overcast, light-polluted sky.

Likewise, the color selection is necessary in Crepuscular Beam, where the gold denotes sunlight, the soft pick and gray, the morning sky. Red shows in Missing Things I’ve Never Known, as the most primal of colors, and is also paired with blue in There Is No Fixed Place (2017), to designate the dualism between base emotion and intellect.

Heather Mekkelson, In Absentia Luci, 2017, elastic, aluminum, latex-toned paracord, nylon cleats,

Room dimensions 16x16x8’, 4th Ward Project Space, Chicago, Illinois

In conversation it was noted the importance of time spent in the studio. Also, we discussed the fabrication and use of materials. Some works look to have been machine-made, for instance in “Now Slices” (2015, 65GRAND). Can you discuss the selection process and pairing of materials? How do you hope the audience sees this aspect in your practice?

I do place an emphasis on personally making work for my own haptic knowledge, but I don’t take a stance for or against fabrication in general. Most often I’m working with a small budget that doesn’t allow me to hire outside fabricators. In the instances where I’ve secured funding, I have hired fabricators to build a custom base or a mount to my specifications—or to apply a certain surface finish. These are elements that I couldn’t produce with my studio capacities. There are also certain sculptural elements that are repurposed items, like the beam splitter glass used in Velocity and Stillness (2015). I’m comfortable utilizing all kinds of items and materials without an imposed hierarchy. It is all equally material to me.

Pairing or combining materials creates a kind of conceptual synthesis that mirrors the merging of ideas. Every thing brought into a work carries its own associations and I consider them carefully, but I really love how the weight of a thing complicates the result. If the viewer wants to follow me down these paths of association, I’ll happily bring them along. It is not imperative however. The point is to confront an object that is not quite familiar, nor completely alien. It is a wholly new presence with an entry point particular to one’s perception.

Heather Mekkelson, Velocity and Stillness, 2015, beam splitter glass, tin bismuth alloy, epoxy, powder-coated steel, 36x22x6”, 65GRAND, Chicago, Illinois, Photo credit: James Lambrix

What do you value most in your artistic practice?

The freedom to ponder any question I have, and a headspace where I can dwell on unity and elegance.

We are now midway through 2018. What are you currently working upon? Any upcoming exhibitions? What’s the plan for the remainder of 2018?

I’m in my studio working on time portals and thinking ahead to 2019 exhibitions.

Heather Mekkelson, artist, in her Logan Square studio, Chicago, 2018

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Heather Mekkelson, please visit:

Heather Mekkelson – www.heathermekkelson.com

Artadia – https://artadia.org/artist/heather-mekkelson/

Art21 Magazine – http://magazine.art21.org/2013/05/28/centerfield-hindsight-and-heather-mekkelson/#.W0YEPthKhp8

65Grand – www.65grand.com

4th Ward Project Space – www.4wps.org

NewCity – https://art.newcity.com/2012/09/11/portrait-of-the-artist-heather-mekkelson/

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello

1. John Durham Peters, https://www.cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/

1389/1467

2. Greene, B. (Brian), 1963-. The Fabric of the Cosmos : Space, Time, and the Texture of

Reality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

3. Herzog MH, Kammer T, Scharnowski F (2016) Time Slices: What Is the Duration of a

Percept? http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1002433