In a highly charged political landscape where immigration and other recurring social issues have divided our country, Hương Ngô examines these topics with subtlety and depth that can only be achieved through intimate experience. Ngô’s Reap the Whirlwind is currently on view at Aspect/Ratio Projects through October 20, 2018. In this exhibit, Ngô reflects on the role of the hypervisible exoticized concubine as portrayed in the early 1900s novels and postcards. This week the COMP Magazine visited Ngô at her Greektown studio to discuss growing up in a family of refugees, her aesthetic process, her Fulbright Fellowship in Vietnam, the current exhibition, and her ongoing research.

Hương Ngô, The Voice is an Archive, With Hong Ngo and Phoenix Chen, Digital Video. Black & White, Sound, 2016

You have a fairly unique experience as a refugee who has studied at a number of top tier universities (University of North Carolina, SAIC, the Whitney Independent Study Program) and established an insightful and timely studio practice. Can we back up a bit and discuss any early experiences that focused your attention on your present day investigations?

Sure. So, I am the youngest of 6 children in a working class family. We moved to North Carolina from Hai Phong, Vietnam after the American war. My family stayed in refugee camps in Hong Kong for almost two years, and I was born during our stay. In the US, my parents worked on assembly lines in electronics factories for most of their lives. I grew up as a shy child, often feeling very perplexed about people, their motivations, and their actions. I often turned to nature as my refuge and to science as my way to understand the world around me. I started university as a biology major and for most of my life, always wanted to be a research scientist.

My family and I were often the “other” multiple times over in our communities. Asians in the US are already often perceived as being perpetually foreign. As Southeast Asians, our history is different from East Asians who might have been in the US for generations. My family was from the north of Vietnam so our history in relationship to the war is different and our reason for leaving (persecution of ethnically Chinese) differs from many other diasporic families, most of whom are from the south. On top of that, I grew up in the American South, so I think I learned to observe and navigate these many matrices of difference from an early age. I didn’t have the language for it then, but my childhood was shaped by a number of very important intersectionalities.

I started making early in life out of necessity – we simply didn’t have many things, so we made or repaired them. Objects in my household were treated with great care. My father was always fixing and tinkering, my mother always knitting. So, my first impulse to make things came early and from a practical, problem-solving perspective. My father would give me electronics to take apart and my mother taught me to hand sew. I was always surrounded by people, so collaboration came quickly and naturally in my practice.

Hương Ngô, In(di)visible installation photos at The Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston,

Thursday, March 8, 2018. (Photo by Michael Stravato)

Hương Ngô, And, And, And – Stammering: An Interview, In collaboration with Hồng-Ân Trương, Performance and Installation with Wood, Archival pigment print, Two-way mirror, Video on monitor, Library, Archive documents on paper, 2010-2017

With Hồng-ÂnTrương, you interviewed/interrogated a number of people in a live performance, And, And, And – Stammering: An Interview, (2010-2017). Though immigration has been an ongoing issue of contention throughout American history, the topic appears to be at fever pitch at present. I’m wondering if you can discuss the role perceptions of citizenship plays in this or other works?

A distinct memory that I have from when I was five years old was taking photos for our naturalization papers in the backyard of our house, and my parents proudly coming home after taking their citizenship test. It occurred to Hồng-Ân and I that birthright citizens have never had to go through this exam, so we used that as a departure point for this project that examines the interrogation itself in order to imagine other possibilities for citizenship.

Perception is crucial in this process as the tests are not actually determining how good of a citizen you will be, but more often how well you perform your belonging based on invisible, unspoken, or implicit rules. Currently, our interrogation performance combines questions from naturalization tests, detention during the years of Chinese Exclusion, Visa and Green Card questions, and more recently questions posed to those detained at the border during Trump’s Executive Order 13769, commonly known as the Muslim Ban.

Recently, we have been expanding the project to look at the material and architectural forms of these interrogation sites to understand how, not only the verbal language, but also the visual language of the citizenship-granting state relays its intentions and exerts its power.

Hương Ngô, And the State of Emergency is Always a State of Emergence, Installation with black poster paper, black gaffer’s tape, cyanotypes, sand, plaster, studio refuse, framed archival pigment prints, 2017-ongoing

Hương Ngô, And the State of Emergency is Always a State of Emergence, Installation with black poster paper, black gaffer’s tape, cyanotypes, sand, plaster, studio refuse, framed archival pigment prints, 2017-ongoing

Hương Ngô, And the State of Emergency is Always a State of Emergence, Installation with black poster paper, black gaffer’s tape, cyanotypes, sand, plaster, studio refuse, framed archival pigment prints, 2017-ongoing

You currently have a solo show, Reap the Whirlwind, at Aspect/Ratio. This series is an extension of ongoing works, yet you are focused upon the exoticized concubine as seen in novels. What prompted this shift? Can you walk us through your process?

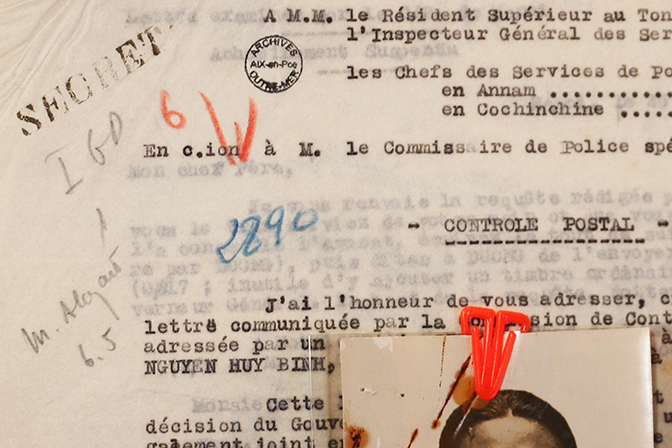

I wouldn’t say that it was a shift, but more of a different lens. All of my work involves the unearthing and shining of light on stories that connect me to larger histories, particularly ones that are not well known or have been rendered invisible via the many ways in which we attach value to one body of knowledge over another. This body of work began in a similar way. I learned that the police records of Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, the most well known Vietnamese woman in the anti-colonial movement, is housed in the Archives nationales d’outre-mer in France. Before this, I thought that these women were just a myth and to find out that they were real – with records sitting in this dusty archive – well, I just had to see them with my own eyes! So the project began with just a desire to be as close to this history as possible, but once I had the document in my hands, I knew I had to do something with them.

For Reap the Whirlwind, I had found out that there were novels that feature Vietnamese (Indochinese) protagonists that were concubines (con gái or congaï). I was curious about how the writers portrayed these characters and the structures around them. My grandparents were involved in the resistance, so I’ve always been curious about what their lives might have been like and what ideas surrounded them, so engaging with popular media from the early 1900’s in Vietnam, from French, Vietnamese, and English sources, is getting in touch with their world in a way. In addition to novels, I’ve also worked with newspapers, magazines, and a play from the same time period. My mother and grandmother both wrote poetry, and literature has always been a big influence on both my mother and me. Placing the archival documents and the popular media in relation to one another is a way for me to complicate the representations of these women and to intervene on the archive itself.

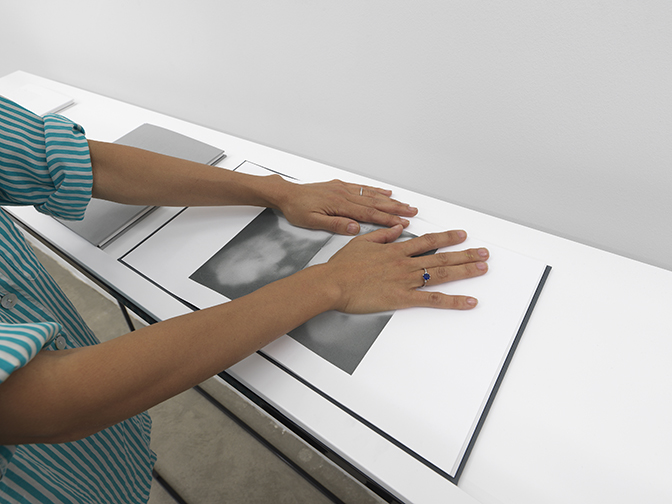

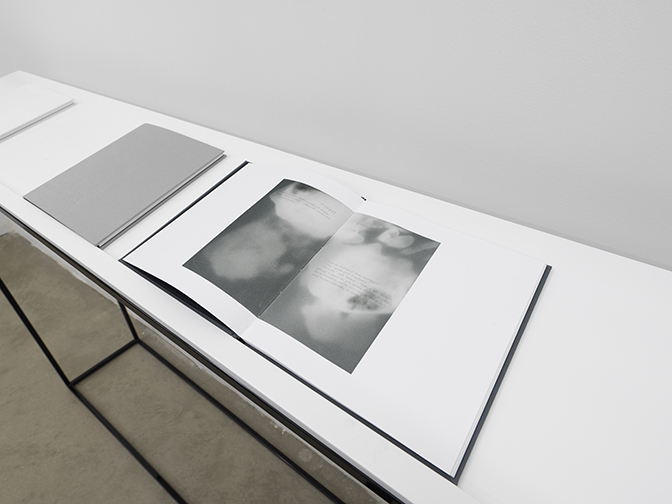

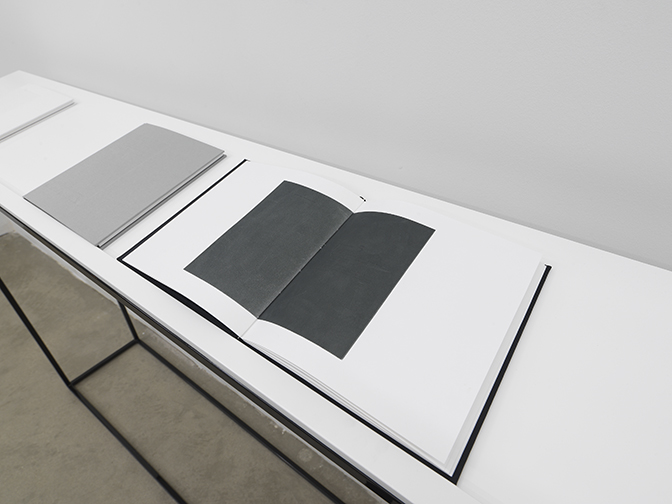

Hương Ngô, Reap the Whirlwind, Serigraph, Artist book in 5 volumes, Custom armature, Digital video, Framed laser cut onion-skin paper on teak, Novels, Bricks, Archival pigment ink on Photo Tex, Ink and toner on paper, 2018

Hương Ngô, Reap the Whirlwind, Serigraph, Artist book in 5 volumes, Custom armature, Digital video, Framed laser cut onion-skin paper on teak, Novels, Bricks, Archival pigment ink on Photo Tex, Ink and toner on paper, 2018

I see your formal aspects being highly controlled and minimal in appearance. You often use opaque blacks and canvas colors in works like And the State of Emergency is Always a State of Emergence (2017-ongoing). Can you discuss the tactile material selection and production in relationship to the conceptual content?

I really enjoy material research, and I try to have the materials do as much “work” as possible such as communicating tone and eliciting a visceral response from the viewer. In the project that you mentioned, the bed is made out of a simple construction paper that has been delicately folded into these structures. Many people think the bed is metal until they are about the leave the space, and then do a double take. I love to think about the way that your body imagines sensation and what happens when there is a discrepancy between what we know and what we feel. For instance, when I was younger, I used to spend everyday, all day in the pool during the summer. When I got home, my body still thought that it was in a pool, so my brain would somehow recreate the sensation, and I still feel like I was in the pool. I like to think of what happens when the viewer realizes that the bed is not metal, but paper, and therefore, will react to the weight of a body in a completely different way. This, to me, is a pathway to empathy – an ability to imagine what an experience might be like. I think literature operates in a similar way.

For this project, I completely indulge in materials and hands-on processes. In addition to the bed, there are cyanotypes on fabric that are made solely from the light of the sun and a moving body of water. I did not use any photographic negatives or objects to create those images, but just put the cyanotype fabric on the edge of the water and magically enough, it creates an image of the sun and water, just in reverse (the blues come from the exposure to light while the whites come from the cyanotype mixture washing out of the fabric). I also make plaster pieces in the shape of Spam cans using detritus from my studio. Those sculptures were based on a story that my sisters told me about staying in refugee camps in Hong Kong. They would take the cans of meat given to them as their food rations and trade them in the local market for fresh vegetables. So, I was thinking about how we create value out of things that don’t have value to us – how we make meaning and build resistance out of our struggles – and how that can look like “breaking the rules.” Though I never studied performance in a formal way, I was influenced by Gutai, Theater of the Oppressed, and radical pedagogy early on, so my work often begins in performance as a means of transformation and becoming. So the work is often a mix of a process-based, performance approach and a close observation of materials.

Hương Ngô, Reap the Whirlwind, Serigraph, Artist book in 5 volumes, Custom armature, Digital video, Framed laser cut onion-skin paper on teak, Novels, Bricks, Archival pigment ink on Photo Tex, Ink and toner on paper, 2018

Hương Ngô, Reap the Whirlwind, Serigraph, Artist book in 5 volumes, Custom armature, Digital video, Framed laser cut onion-skin paper on teak, Novels, Bricks, Archival pigment ink on Photo Tex, Ink and toner on paper, 2018

Hương Ngô, Reap the Whirlwind, Serigraph, Artist book in 5 volumes, Custom armature, Digital video, Framed laser cut onion-skin paper on teak, Novels, Bricks, Archival pigment ink on Photo Tex, Ink and toner on paper, 2018

In 2016 you received a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Grant in Vietnam. Can you share with us what you did? What did you find to be most rewarding in this experience?

My official role was as an educator and a researcher. I visited a number of universities and gave lectures on intersectional feminism in the arts. As a researcher, I visited museums, libraries, and national archives to gather information about women in the anti-colonial resistance. Because the colonial archives was split between Vietnam and France after Dien Bien Phu, the end of France’s occupation, I was curious to see how one archive might inform another. I was in fact able to do this, and some pieces that I produced would not have been possible without research in both countries.

However, the richest part of the experience was simply living in Vietnam and learning from fellow artists about what it was like to live and work in a Communist regime. In Vietnam, protest is not allowed, and more recently, online dissent has been deemed illegal. Artists and foreigners are seen as a threat to the fragile stability of the authoritarian government, so even a small intervention or action is heavily policed. Regardless, artists and citizens risks their lives and their safety all of the time to protest injustices. It was incredibly inspiring to witness this, but sadly, does not feel at all so different from our situation in the United States.

Hương Ngô, To Name It Is to See It (In Passing I), Archival pigment print on silk habotai, custom armature, 2017

What do you value most in your aesthetic practice?

I have always been interdisciplinary. I fought this tendency for many years, believing that I had to be an expert at something, but eventually I just gave up and let myself engage with all of the materials and processes that I wanted and needed for the work. Eventually, I was able to value my versatility and adaptability and see them as strengths. I am interested in relationships between materials and what that can communicate. I enjoy spending time listening to materials and learning from processes. I think I am the ideal audience for those weird Youtube videos that just show you how things work! I also love the ability of art to infiltrate other disciplines and incorporate them. In my opinion, art has always been interdisciplinary, and it has just take some time for the art world to realize that.

Hương Ngô, To Name It Is to See It (Existing Surveillance Photographs) (detail), Archival Pigment Prints

on MOAB Metallic Silver, 2017

You are currently exhibiting, making work and teaching. I am wondering if there are any other efforts or projects you hope to begin or call closure to in 2018?

These last couple of years have been really tough, and we are headed for more struggle as inequality in our society rises and our political landscape continues to move towards the subtle but effective disenfranchisement of its citizens and civil society that openly supports patriarchy and white supremacy. Like many artists, I’ve been working on leaning into the efforts towards social justice. As the youngest child in my family, it has been hard for me to embrace the power that I do have in society, but there is no time to hesitate now. All of us need to understand the power that we have and use it to increase empathy, openness, and the multiplicity of narratives in our world.

Hương Ngô, To Name It Is to See It (We are here because you were there. Chúng tôi ở đây vì quí vị đã ở đó. Nous sommes ici parce que vous étiez là-bas.) Installation of hectograph prints and hand-cut paper with custom typeface, theater lights,

2016 – 2017

For additional information on the research and aesthetic practice of Hương Ngô, please visit:

Hương Ngô – http://www.huongngo.com/

Current:

Aspect/Ratio – http://www.aspectratioprojects.com

Past:

Museum of Modern Art – https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3886

Upcoming:

University of Illinois Springfield Visual Art Gallery – https://www.uis.edu/visualarts/gallery/

4th Ward Project Space- http://www.4wps.org

Hương Ngô, artist, Chicago, 2018

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello