Having been raised out west in the 1970s in a family where arts and crafts activities were common, it is not entirely surprising that Jeffrey Grauel’s aesthetic practice uses materials often aligned with this time period. What becomes fascinating is how and why Grauel, while working today with seemingly antiquated items, grapples with the iconography and ideas associated with the past. His works require the viewer to consider the noted (representations and substance) from varied vantage points (interpretative and physical). This week the COMP Magazine hiked up to Grauel’s Lakewood-Balmoral studio to discuss with him his youth in southern California, how an 800-pound Gorilla became the foundation for his ongoing investigations, a couple of recent series (Hides and Shags), his interest in unconventional materials and the running of the experimental gallery, Slow, in Pilsen.

my parents’ hair, platinum, 2013-2016

Though you have been in Chicago for some time, you are from out west and grew up in southern California. One of the items that came to note when discussing your work was the role arts and crafts of the mid 1970s hold in your memory. In addition to this, I’m curious if you can identify any early experiences or people who impacted you in your youth that set you on your current aesthetic investigations?

Seems like everyone around me growing up had at least one creative hobby, especially my family members. Talking to my father recently he reminisced about a particular model plane he made when I was a kid. He made several but this one was modified to accommodate an egg decorated as a pilot. Together we entered an egg decorating competition at the local library. They printed a picture of us and our eggs in the local paper.

Another of my father’s hobbies was wood carving. Two of the reliefs he carved have lodged themselves in my mind. They are the back profiles of a girl and a boy. The girl in a patchwork dress and bonnet, the boy in denim overalls and a straw hat, very 1970’s. He based them on poster illustrations. After my father retired he was excited to start carving again and found it too painful so he gave me his carving tools. This was devastating because I was excited to see what else he would carve.

My grandmother was an avid sewer. One of her creations was a mouse broom cover. Similar to the girl in my father’s wood carving, the mouse wore a bonnet with a calico dress and a white apron. It slipped over a broom handle and the mouse’s dress covered the brush. It fascinated me because it was only for decoration. The broom was bought to support the cover. It was never uncovered and used to sweep. That seems to happen when folks are crafting. The decoration takes over and the practicality gets lost/ignored/was never the point? It makes my head spin.

Lets begin with discussing the two series Hides and Shag series. These most recent bodies of work combine kitsch, fiber arts and sculptural elements that setup a unique strategy for viewing and considering the content. Can you walk us through the conceptual and tactile process of these series?

Those weren’t meant to be artworks. They started as a technical experiment. My idea was to make a rug so I could brush its fibers apart, and then I would use the fibers to practice making felt. Not that far into my frantic brushing I stopped to consider the rug. It was so odd. The image was only visible from the back, so if I wanted to display it I would need to convince people to walk around it. That lead to finding the funeral wreath stands.

I made a few more and got really interested in the patterns I was finding. Particularly ones that were made around the time I was a kid. Many register as nostalgia for conquest, the West, space, the ocean, sports. It’s interesting to take those images and burry them in pile. They become both hidden and inherent. The titles point to more layers. Calling them hides, as if they are skins pulled off to reveal tattoos. Or shags, to borrow the slang, implying something that is f***ed.

52 x 24 x 19 inches, 2018

52 x 24 x 19 inches, 2018

800-pound Gorilla is a work that you began in 1998. In this you create an Afghan crochet works in the dimensions of the rooms of your parents’ home using acrylic yarn. This effort has gone through a variety of transformative stages. Can you discuss what piqued this project and the ephemeral nature that attached itself to this work?

That body of work is the foundation of my practice. It’s the heavy shadow I can’t seem to shed. It was conceived in response to the void that opened when I moved away from my family. Similar to a black hole in space. Not an absence, but a gravitational force so strong that it collects everything. All light and matter. Stunning and terrifying at the same time. Impossible to describe.

Rather than stopping at the initial parameters of the project, I wanted to keep manipulating the materials to see far I could push them. It was also frustrating to carrying around those massive blankets when I moved from apartment to apartment. So yarn went from blankets to rugs to felted bricks. And then I started to question my labor as a source of transformation. So, for the last iteration I commissioned a company to do the labor. A diamond made from my parents’ hair seemed like the farthest I could get from where I started. A large gangly pile of knotted acrylic yarn devouring light, to a perfectly ordered, transparent tiny jewel that could be easily be overlooked.

48 x 16 x 16 inches each, formerly Afghans crochet in the dimensions of the rooms of my patents’ house, 2003-2009

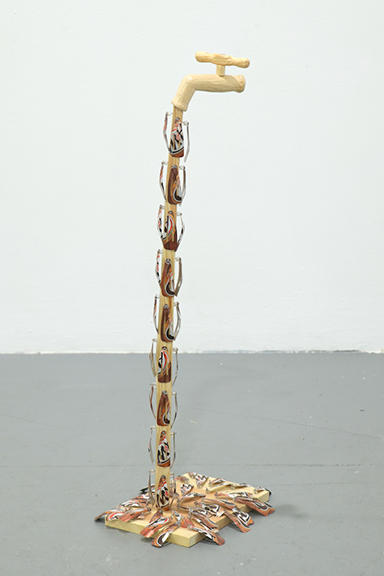

Can we discuss your process for selecting materials in relationship to the content and ideas you are investigating? You work in a variety of nontraditional media. For instance, in Eternal Font you use scrap lumber, pony beads and soda cans to create recognizable items (e.g., doors, buckets and faucets). Can you share with us your process of selection in relationship to the message you hope to convey?

The cans are a good starting point. They remind me of all the recycling we did when I was growing up. We spent a lot of time collecting cans, cleaning them, crushing them, taking them to recycling centers. My grandfather had a sledgehammer that he would use. He would put a can down on a brick and let us drop the hammer on it. There was pretense that the money earned from the recycling would go into a saving account that would help pay for my college education. For all the work we did, it didn’t amount to much. It was kind of a waste of time but the production was fascinating. The overall forms of those sculptures relate to the antiques my mother collected and displays around her house. With those sculptures I’m layering up things I’m attracted to. They relate back to the mythology of the West. Dusty ghost towns and carnival shooting ranges.

soda cans, pony beads, 34.5 x 12 x 9 inches, 2016

In addition to your studio practice you collaborate with Paul Hopkin in the running of the gallery space Slow (and Loo). Known for presenting thoughtful, yet challenging, work by a range of artists, Slow has established itself as one of the city’s more innovative sites for encountering contemporary art. Does this activity have any impact on your working practice? Can you describe your curatorial practice?

It has the most impact. It provides a direct connection to the art community in Chicago. Our side projects at the gallery feed into that. The beer brewing we do requires hours of downtime that allows us to talk about all manner of art related business. Several folks who have brewed with us have been astounded by those conversations. We’ve been encouraged to record them, but it just doesn’t translate. They are more about an engagement rather than us pontificating.

I’m the most reluctant curator you have ever met. After the first exhibition I organize I emphatically swore I would NEVER do it again. Curation is a lot of work. It requires a set of skills that are not fun. Relationship building, communication, planning, communication, scheduling, communication, a bit of design, and a lot more communication. When I do curate, I work with artists I know and get along with. The bathroom gallery, Loo, works because the stakes are so low it can be all fun and games. If it’s a disaster, its fine because it’s just the bathroom.

What do you value most in your time spent in the studio?

Studio time is hard for me to identify. I tend to work on my artwork all over the place and at odd hours. Recently I was renting a dedicated studio space and at some point I said to a visitor, “This is obnoxious,” pointing around to the space. I felt like I was just paying rent to prove I was an artist. Nothing about the space was inspiring and I was wasting time commuting to it. Early in my career I challenge myself to build my practice in a way that I was not reliant on a studio.

That has also fed into where I show my work. I’m drawn to unusual settings for exhibitions. I really like the additional layers an environment adds to artwork. Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about spontaneous memorials. It’s shocking to stumble across one. To wonder about what or who it’s memorializing and the events that took place at that spot. You analyze the area to look for clues, but often there is every little information. Candles, pictures, stuffed animals, a bent sign post, a bike painted white, flowers, a flyer asking for witnesses.

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Jeffrey Grauel, please visit:

Jeffrey Grauel – https://www.jeffreygrauel.com

Chicago Artist Coalition – https://chicagoartistscoalition.org/artists/jeffrey-grauel

Chicago Magazine – http://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/April-2019/Insiders-Guide-to-the-Gallery-Scene-You-Dont-Know-About/Its-a-Bathroom-Its-a-Garage-Its-a-Gallery/

Maake Magazine – http://www.maakemagazine.com/jeffrey-grauel

Slow Gallery – https://www.paul-is-slow.info

The Visualist – https://www.thevisualist.org/2019/06/breach-of-contract-artist-talk/

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello