The studio of Ji Su Kwak is spartan. Neatly organized in the space are a couple completed works, a couple shelving units with just enough materials to continue experimenting with on new projects, a small table with a laptop, one chair, and a stool. Her practice takes on a nomadic being. This judicious approach can also be seen in her aesthetic output. Kwak investigates big ideas with a discreet mindfulness. This week the COMP Magazine headed over to the west side near Union Park to discuss with Kwak her life’s travels, her process for selecting materials in relationship to content, the role political events impact her work, and what she plans to do when she returns to Korea.

EuroGraphics Map of the World Puzzle (1000-pieces), size variable, 2017 – ongoing

From our conversation I gathered that you have been somewhat of a nomad. You are South Korean, lived for time in Vancouver, British Columbia, China, and now reside in Chicago. Can we begin with you sharing with us a bit of background? Perhaps, you can identify how these places have impacted the way in which you look at the world and how this informs your current art practice?

Overtime I changed my name and appearance, adapted to different cultural upbringing, and prayed to different gods depending on what part of the world I was dwelling and to whom I was calling my mother. I moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, when I was eleven years old. For eight years I lived with various homestay families. More precisely, I was in and out of fifteen or more different homestays. I remember the moments I returned back to the other side of the window watching my previous families carrying on with their lives without me. I moved on for another real family with a van full of furniture and boxes of sundries.

The journey carried on – in Beijing and Chicago – through numerous families, communities, friends, and lovers. Everywhere I went, I was greeted with, “you are one of us now” and left with, “you are too…” Korean, Asian, feminist, young, old, sick, healthy, religious, or profane. In the beginning, I was obsessed with the idea of home and community. I created works about what makes a perfect home and why I cannot be part of it. This practice was my way to understand what was going on.

It was not until my biological father told me that I was “not Korean anymore,” that I realized my identity had been molded by my surroundings to differentiate who gets to be in or out. That made me ask myself why I had been trying so hard to fit in. Being in a community brings a sense of belonging and power, which is valuable. Nevertheless, there is a comparable value in being an outsider. Now, my work is about my presence as an outsider, which I relate to as a fluid identity; I can appear, manipulate, and evaporate anytime and no one will question.

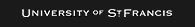

I’m fascinated by your selection and application of materials. The work, Balanced Talk, 2019, utilizes a brass balance scale and sugar. With the sugar you write, “You Never Listen” and “Why Don’t You Talk” in the two trays of the scale. The weight of the sugar in each tray is in equal measurements, therefore the scale is balanced. Can you discuss this work and its intent?

When I was working on the Balanced Talk, I was thinking a lot about what justice means. It seemed to me that when people recognize themselves as outsiders of a problem, they tend to judge based on the different standards that they have. The same goes for me, too. The most common example would be when I tactlessly volunteer to judge between my parents.

I took the two phrases in the work, “You Never Listen” and “Why Don’t You Talk,” from my parents. These two are the most frequent phrases my parents say when they argue. As none of these correctly answers another, the conversation falls into a swamp turning round and round. Eventually, I realized that I think or even say these phrases sometimes when arguing with a lover. Who doesn’t? Even though we all know that this is not going anywhere…

In Balanced Talk, I started off with a more experimental approach. I was curious to see how a manufactured measuring tool would determine the weight of language and relationship. The phrases written in piles of sugar were so light, but heavy enough to lift, sink, and balance against each other.

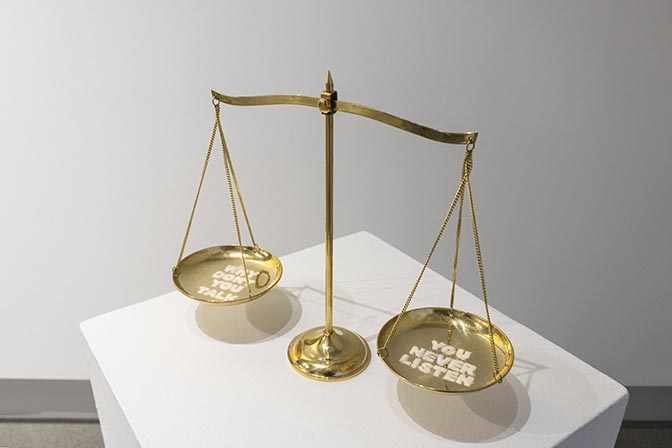

Though not abstract, there is a bit more contemplation needed for entry into the work 15 Ways to Say “Hello”,2018. The piece consists of 15 clay hand imprints that hide text beneath that appears to have been laser etched into an acrylic base. The sentences have been taken from remarks on foreign countries made by President Donald Trump. What prompted this work? Can you walk us through its creation?

The idea for 15 Ways to Say “Hello” sparked during my residency at ACRE. I was having a conversation with one of the staff about how the common phrase, “I like your shoes,” feels so odd to me. “It is a way to say hello,” they said. I guessed it was similar to the greeting phrase, bab-mukutsuh?, meaning “did you eat rice (food)?” in the Korean language. But the feeling of oddness continued. I wondered how hellos are expressed between different cultures with the respect that neither “I like your shoes” nor “did you eat rice” makes sense.

Then I started to research President Donald Trump’s remarks on foreign countries. Many of the remarks were not very friendly. Eventually, I noticed how most of them were simply put and emotional. They were easy, or sometimes too easy, to understand. To me, they read like a note being passed in a class or words that frustrated lovers would utter. Then I decided I wanted to become an amateur mediator for these remarks. The only thing I did was switch the original pronouns of the mentioned countries to “you,” “them,” “her,” or “him.” And they really became lines from a romantic.

Alongside with the revised sentences, I created clay objects, each intended to pair with a sentence. I mimicked various hand gestures shared by two individuals, such as brushing, pulling, folding, and etc., and created imprints of these gestures in the clay. The clay objects are meant to offer tangibility, but also to confuse. I think there is a sense of preciousness and trust when we are guided to hold something and read. I hope the audience get the impression of personal or warm story upon seeing the work for the first time, but later find out about the true story. Neither of the hand gestures nor the phrases are authentic.

MDF, wall paint, spray paint, varnish, cement, graphite, and door hinges, 71.3 x 382.8 x 11”, 2017

MDF, wall paint, spray paint, varnish, cement, graphite, and door hinges, 71.3 x 382.8 x 11”, 2017

You are an interdisciplinary artist who works in a variety of traditional and new media. Can you discuss the role the art medium plays in your practice? What prompts you to make specific selections? How does this relate to the time in which the artworks have been produced?

When working on a project, I usually look for an object or gesture that plays a significant role in an event that my project is based on. In my older work, Safety First, I recreated a safety fence into a folding screen because the Blue House in South Korea was enclosed with the fence to block the disappointed civilians. For Praying Bench, I spent many days just rubbing my hands to come up with an object that can function as a hand rubbing device. I decided to create my own at the end.

The choice of my art medium really depends on how I want my audience to experience the work. Sometimes I compose songs played in a music box because the interaction of the audience to make the song play is very important. I once created a children’s song with a cheesy illustration with an intention to create a satirical slogan. Sometimes I simply draw on a flat surface because the imagery of the pictures is most important.

Recently, however, my selections for artmaking has shifted drastically because my VISA is expiring soon. As the time for me to pack and move is coming closer, I looked for light-weight and foldable materials to work with. Now I feel that I yielded too much to efficiency and practicality. Once I am settled, I would like to go back to how I chose my materials when I did not have to worry about moving.

You are currently working in the studio and plan to return to South Korea this summer. What are you currently focused upon? Do you have specific plans upon your return home? Are there any exhibitions or other projects on the horizon?

I have an upcoming group exhibition at ACRE in September, curated by Lucy Stranger. This is exciting because all of us in the show(Renee Yu Jin and Dominga Opazo), create very different works. I am anticipating to see how all of our work will come together in the space.

I am currently taking a break from artmaking. Only after a while, I realized how crucial physical strength is in maintaining a studio practice. Although I am continuously making notes on ideas and experiences, I will not be doing any physical making until I am well again and return back home. My plan after the return is to begin working again. Also, I plan to attend a graduate school in studio art in Korea. I am excited to learn how to talk and write about art in the Korean language and how the perspectives of Koreans in experiencing art may differ from here in the United States.

I have always faced limitation in creating works about Korean politics because much of my knowledge is learned from the news media instead of an actual experience. I feel that it is necessary for me to live there to clearly understand what is going on and decide where I can stand and support. I have a strong feeling that living and working in Korea will bring about new developments or even change my perspectives and ideas very much.

bronze castings on steel rods, 60 x 3.5 x 6”, 2017

bronze castings on steel rods, 60 x 3.5 x 6”, 2017

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Ji Su Kwak, please visit:

Ji Su Kwak – https://jisukwak.com

Circle Foundation for the Arts – https://circle-arts.com/interview-ji-su-kwak/

Alienable Rights at Slow Gallery – https://www.paul-is-slow.info/blog/2018/8/24/g3ac7088398g0a5g2ddmfixkoyfjz9

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello