There is a sensual luminosity in the elegant approach to visual meditation in the practice of artist/photographer Julie Weber. In her photobook REMNANTS, published by Chicago’s Skylark Editions, light experiments, and installation works one finds a clean and clear translation expanding investigation that references formal elements and ideas that stem from experimentations that date back to the inception of the photographic medium. This week the COMP Magazine caught up with Weber in her northwest side studio to discuss how she uses her studies in the natural sciences in her practice, sensory optical analysis, the importance of the photobook as artifact, and what luminous activities are on the agenda for 2019.

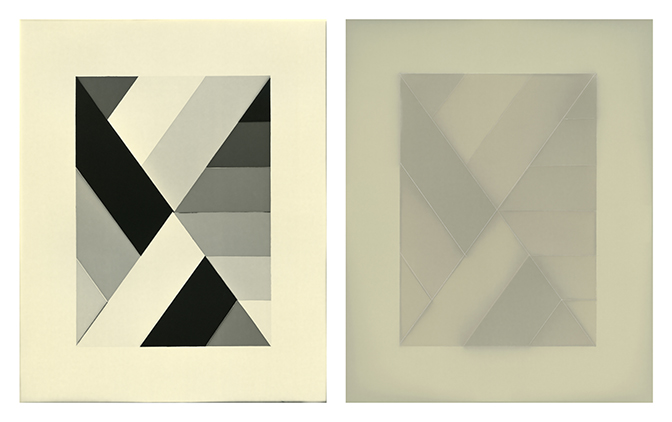

Julie Weber, 1403.04.L (Undisclosed Typologies), 8 x 10 inches, 2014

You grew up in Chicagoland, have spent time living abroad, and have a close connection to the sciences. The latter is clearly evident in the works you produce. Can we start with you identifying any early experiences or people that piqued your interest in the intersection of photography and the sciences?

Honestly, I owe a lot of credit to my undergraduate experience at Dominican University (River Forest, IL) for this. Their liberal arts curriculum was, as it should be, highly diverse but it did really well to encourage questioning, recognizing, and exploring the gray areas between the things learned in such black and white terms in early education. While there I became particularly interested in research methods within the social sciences. I studied qualitative and quantitative systems within psychology and sociology; I had a knack for weighing hard and soft scientific aspects against perceived rigor and objectivity. This led me to a brief but formative tenure as a researcher in cognitive testing within drug development.

My background in research certainly influences my approach to photography, which is concerned with experimentation, methodology, and illustrating process. In science, replication is crucial for establishing a hypothesis as theory. In my practice, I am more interested in the presence of subtle variation or iteration through repetition. Scientific framework can be a bit rigid and based on precedent, so while I use methodologies in my practice, my application of them is less traditional, which appears in my work through manipulating photographic materials in unconventional ways.

Photography is a science – one of light and image formation with roots in physics and chemistry. It is the application of photography that is so sweeping and ubiquitous. Art is just one of the myriad forms photography takes but it is the one that fascinates me most because the use of it for self-expressive means seems so counter to what the medium is capable of. It often seems a fool’s errand to attempt expression of visceral things through a medium renowned for its optical exactitude.

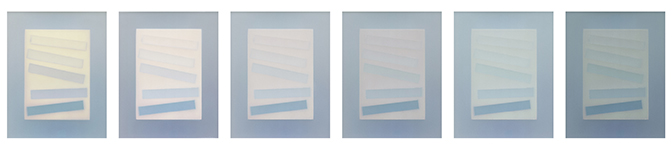

Julie Weber, Ascending Gradient (Forte Fortezo G4 FB) [across 5 weeks], 14 x 11 inches, 2017

Julie Weber, Detail of Ascending Gradient (Forte Fortezo G4 FB) [week 0],

14 x 11 inches, 2017

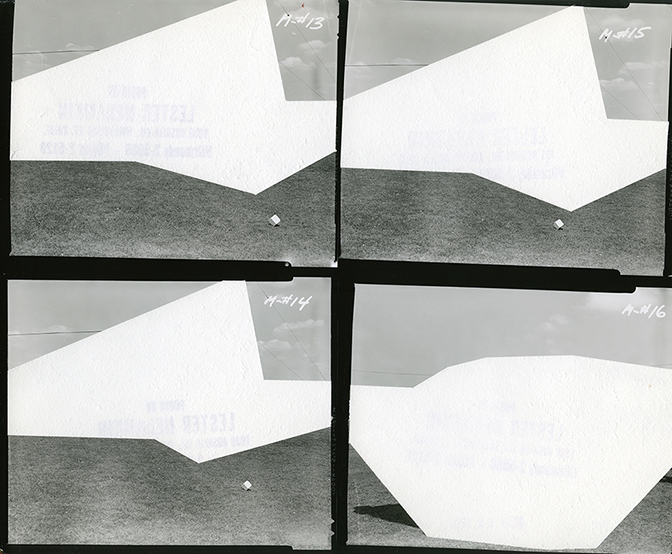

When viewing works found in the Undisclosed Typologies series (2013-2015), I am drawn to how removing the primary subject matter creates an abstract/non-narrative interpretation. What prompted this format of inquiry?

In a broad sense, I think photography is popularly thought of as synonymous with representational imagery. And in an art context, I think photography relies too heavily on the image to ascribe meaning. I wanted to get away from the image as the dominant subject matter and instead emphasize the photograph as an object with a lived history.

Just before this body of work began to take form, I was experimenting with adding materials to found photographs. Introducing stickers, or paint, or staples, or thread, and whatever else I was using at that time, felt little more than decorative. These trials, however, made me realize I wanted my intervention with the photograph not to distract by adding disjointed materials and concealing, but rather, I wanted to point out what was already there simply by revealing. This led me to the process of applying a series of straight incisions around the main subject matter and peeling away sections of emulsion to reveal the textured white paper base beneath the image.

Repeating this process over and over to a number of photographs made me appreciate how variable photographic paper can be, which in turn led me to exploring photographic papers in the Light Sensitive works.

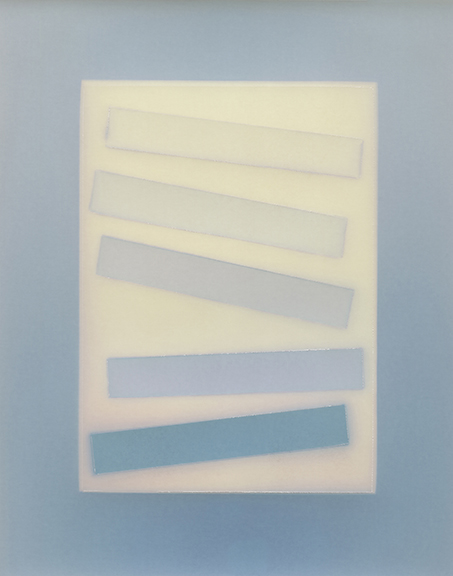

Julie Weber, Descending Gradient (Ilford Multigrade FB) [across 5 weeks], 14 x 11 inches, 2017

Julie Weber, Detail of Descending Gradient (Ilford Multigrade FB) [week 0],

14 x 11 inches, 2017

Julie Weber, Detail of Perceived Transparency (Kodak Polycontrast III RC) [week 0],

20 x 16 inches, 2017

You have created a number of bodies of works that you categorize in the Light Sensitive series. I see a direct connection in these investigations to that of early 20th c. artists (e.g., Lázsló Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, Curtis Moffat). Specifically, there is an attention to formal qualities that are centered on optics. What fascinates you about this approach to photography? Do you draw any insight from past practitioners?

Absolutely. For me, it is largely about context. In the 1830s, photography was concerned with inventing itself by creating a lasting image. So much wondrous experimentation – successful and unsuccessful alike – came from this, without ever having the intention of being ‘art’. In the 1920s, camera-less and experimental techniques resurfaced in popularity as the medium, 80 years beyond invention, could have a new appreciation for these methods, particularly as it strived to establish itself as an art form. And now, in the present day, we see a resurgence of camera-less and alternative processes arguably as a backlash to the digital age and the loss of transparency in digital photographic process.

I remember in late 2010, I was visiting London and had the good fortune of experiencing firsthand the exhibition Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography at the V&A. Before arriving, I had researched online what exhibitions were on at which museums and when I read about this show, I was overwhelmed at how close to home it hit. When I saw it in person, it sounds cheesy but I remember thinking to myself, “I found my people.” That show really put a framework around the way I was feeling toward photography and gave definition to the work I was making. It also solidified that committing to photography was a worthy endeavor. That December I applied to Columbia College Chicago for my MFA.

To loop back around to your question, photography is a visual experience of light across time – optics is everything. The Light Sensitive works are my way of showing that experience as directly, and in some sense as rudimentarily, as I can. Making this work has led me to consider the effects of visibility – what are the consequences of the ability to see. I’m enamored with this sort of tipping point moment in which light is necessary to create an image but then becomes too much and overwrites itself. Hiroshi Sugimoto once said of his theater photographs something along the lines of too much information leads to nothingness so there must be a container in which to view that nothingness.

Julie Weber, Installation view of Light Chronology at For The Thundercloud Generation in Edgewater, Chicago, 2016

One of the items that comes to mind when I consider your overall aesthetic practice is the time spent in the darkroom and studio. Having worked in a darkroom for a number of years, I found the process to be meditative. How do you think about the time spent in the darkroom and studio? Why is this an essential part of your investigations?

I teach photography classes at Waubonsee Community College where I am grateful to have access to a darkroom, particularly as a lot are disappearing as school curriculums change. Running the darkroom is like running a lab – making sure everything is stocked, replenished, temperature controlled, and operating efficiently. I think of it as a controlled environment that is ideal for experimentation. I can certainly relate to the meditative aspects of working in a darkroom, which is probably why I prefer to work in the darkroom alone. For a medium in which time is integral, it sure is easy to lose track of time and work long shifts amongst the amber glow of the safelight and the flow of paper making its way through liquid baths. My studio space provides a good balance as it is very much the opposite – it is filled with natural light and offers room to spread out my work, sit with it, and share it with others. It is also provides space to observe the change in my light sensitive works beyond the control of the darkroom. And I feel I should add that in a very practical sense, I’m grateful to have these workspaces as I’ve come to find that I work better when I have a space to go to – working from home offers too many distractions.

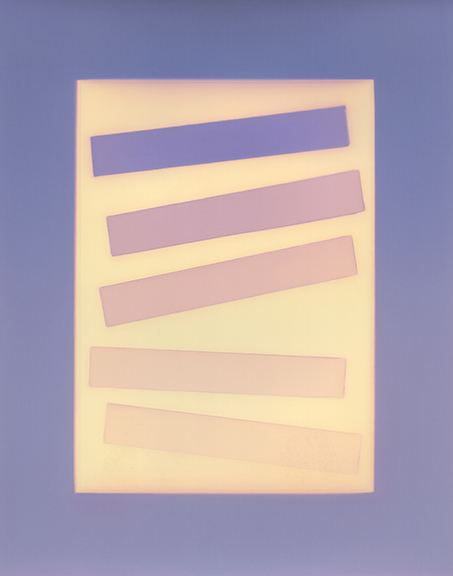

Julie Weber, Two Permutations of Light (Luminos Pastel RC), each 14 x 11 inches, 2016

Another item that surfaces is the hint of chance. When you approach an idea or series of work, what level of the final output is calculated and spontaneous? Does chance or other uncontrollable elements play a role in your practice? If not, how do you eliminate happenstance?

This is a very important question – one that I am routinely asking myself because I think it is constantly shifting. There is often a lot of control upfront in my process. With the light sensitive works, I spend a fair amount of time observing and documenting the response in color of different photographic papers to different light sources. I then use this information to realize a color palate and composition. However, since these works are not chemically fixed and therefore still sensitive to light, once they are displayed, all that control goes out the window as they continue to change color and compositions fade.

While I make efforts to prepare the work and predict its outcome, I do not set out to eliminate happenstance. In fact, I find that happenstance pushes the work forward – what I learn from one installation always influences the next iteration. For instance, Light Chronology allowed me to relinquish control of lighting to the sun as the work was displayed in the windows of an empty storefront, but to minimize how quickly the works would change, I chose to unveil them at sunset. In prior installations, I had worked mostly with just the available and artificial light of galleries. When I exhibited at Bert Green last winter, I had the opportunity to work in a space without natural light. This allowed me to essentially convert the space into a darkroom and fully take control of the lighting, which I did by displaying the works under a safelight and only turning on a regular tungsten bulb for brief intervals. This allowed me to extend the photographic moment into a durational process lasting weeks.

Julie Weber, REMNANTS, published by Skylark Editions, Chicago, IL, 2017

What do you value most in your photography practice?

Definitely the community. It means so much to be able to share my work with others and even more to hear their responses to the work. And it is equally important to experience others’ work and offer response. I think that exchange is key to evolving as artists. I feel very fortunate for the opportunities I’ve had to talk about, exhibit or publish my work, visit a classroom, plan an event, etc., as I get to work with and learn from great people who propel me forward. I make efforts to attend events and shows in Chicago, share opportunities with others, and encourage my students to submit to shows as much as possible. I feel lucky and beholden to be part of the artist community here in Chicago – there’s a responsibility to be an active participant, because that’s the way our community thrives.

Julie Weber, Remnants B-side #8, 11 x 8.5 inches, 2017

What are you currently working upon? Do you have any specific projects coming up in the new year?

I have a couple of works on view at the Illinois State Museum’s Gallery in Lockport as part of the exhibition Untitled (house): The Diane and Browne Goodwin Collection. The exhibition displays over half of the private collection that he and his late wife amassed over the past 40 years and 3 states where they resided. The show is up through April 15, 2019. I grew up in Lockport and went to high school there so it’s extra special to be part of this exhibit.

I’m looking forward to the downtime between the teaching semesters so that I can quietly work in the darkroom and studio. I’m continuing to work with the printer ribbon material that made the REMNANTS book (published 2017 by Skylark Editions) and I’m also exploring the next iterations of the light sensitive work. It feels good to be at the beginning of a period focused on making since I’ve been holding onto a lot of ideas without having enough time to see them materialize.

I’m honored to be a FOTOFILMIC18 finalist, which will take my work on a traveling group exhibition to San Francisco, Seoul, and Vancouver beginning this spring. I’m excited to have a solo show on the books for next autumn – it’s such a luxury to have this much time to develop new work for a show.

Installation view of Untitled (house): The Diane and Browne Goodwin Collection at the Illinois State Museum’s

Lockport Gallery. Image credit: Evan Jenkins

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Julie Weber, check out:

Julie Weber – http://julielweber.com/

Illinois State Museum – Lockport – http://www.illinoisstatemuseum.org/content/untitled-house

Skylark Editions – http://www.skylarkeditions.org/julie-weber-remnants/

Foto Filmic – https://fotofilmic.com/fotofilmic18/

Julie Weber, photographer, Chicago, 2018

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello