Having grown up in Chicago’s South Side neighborhood of Beverly, Kevin Blake’s trajectory in becoming a serious painter (not the kind that pay Union dues) is remarkably unusual. This week the COMP Magazine caught up with Blake at his Ashland Avenue studio to discuss the role art played while growing up in a predominantly blue-collar neighborhood, how his visual practice intersects with literature, what he values most in being in the studio, and how he reveals challenging narratives through merging abstraction with recognizable imagery.

Kevin Blake, The Flower that Stars the Day Begs the Glory of a Wake, oil on paper, 72” x 51.5”, 2017

You are a Chicago native, grew up on the South Side in Beverly. Attended the Art Institute. Can you identify any personal experiences that defined your youth in the city? Also, since you grew up in essentially a working class neighborhood, not known for producing a wide swath of art-types, what role did art play in your upbringing?

I think all people are a product of the environments they are raised in and every household in the world is a nuanced system self-navigating through their misunderstanding of the social world in which they are a small part. While it’s probably true that there aren’t very many south-siders playing the Art game, some of the most adept artists I’ve ever known, never made objects to put on walls.

I think we tend to loose our grip on what art is and who artists are, when they are defined within the institutional boundaries that wring that definition dry. Making art is simply my way of trying to navigate a world full of disparate elements, which to me, is no different than every other profession in the world. We are made with the tools we learn to sculpt ourselves with, and we look like the places we come from. I don’t think that is ever coincidental.

I knew a guy who was a wizard with computer graphics in the late 90’s that made counterfeit gift certificates to a grocery store chain(now defunct) in the $10 variety. Five or six guys would go in to the store at different times and buy a pack of gum or bottle of water and get the $9 change in cash. The yield would then fund larger operations. He was an artist for sure. I knew a girl who made fake coins at the perfect weight for cigarette dispensers. She’d hit the bowling alley, the VFW hall, and every bar on my neighborhood’s strip of Western Avenue. She would sling those packs of cigarettes at the park when we were too young to buy them. She was an artist too, and I’m confident she’s out there in the world plying her trade in some capacity.

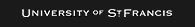

Kevin Blake, The Utility Man with the Papal Leafet, oil on canvas, diptych, each panel 51” x70”, 2017

What prompted your aesthetic investigations?

At a young age, I wanted to be an animator for Walt Disney. I would trace the characters in the Disney Books into my sketchbook, and I would tout my drawings as having been done freehandedly. I had a buddy down the block that shared my interest in drawing, but he was naturally gifted-a much better draftsman than me. It bothered me. It bothered me so much that it made me want to be an artist. That sense of competition never really left me and I’m so stubborn that I’m still trying to make drawings like that kid down the block.

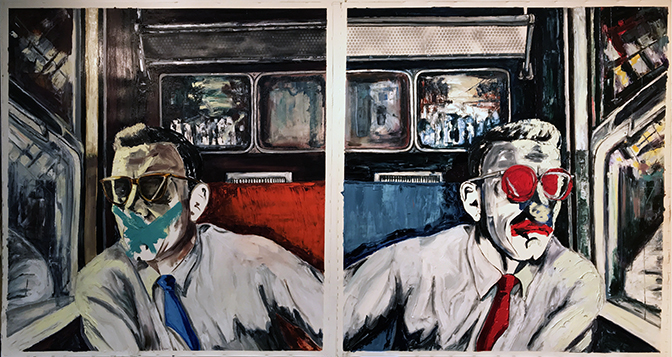

Kevin Blake, He Pulled Her Up His Bucket of Tar, mixed media on paper, 14” x 17”, 2018

In conversation we noted your interest in literature, specifically discussing the poems and writings of Richard Brautigan. Can you share with us the connection you have with literature?

Language is my interest, and with such a concern, literature and it’s history is as much an inevitable part of the landscape as painting and it’s history. When you were visiting my studio, you mentioned that there was something similar to Richard Brautigan in the way you were hearing the titles of my paintings in your mind, and sure enough I have one of his books on my shelf. It’s called, “Trout Fishing in America,” and it was a book I stumbled upon because of my interest in trout fishing, rather than poetry. This scenario reminds me of something William James said, and I’m paraphrasing, but it goes something like this: If we don’t read the books with which we carefully line our apartments, we’re no better than our dogs and cats.

I haven’t read this book from cover to cover. I almost never read books this way. I read books the same way I make images-in intervals. Disjointed. Parsed. It’s the only way to not be infected by the message. I guess I think it’s better to be like the dogs and cats in the apartment. The disconnected ideas about the way things appear to be, are much more interesting to me than the ones that follow more typical patterns because they seem more my own. Every time I open this book, I love the few pages that I read. Brautigan is weird, loose and dirty. I don’t hear my cadence in his, but the fact that you do, is the stuff I’m interested in.

Kevin Blake, The Binocular Boy was Flayful with His Father’s Cleaver,

mixed media on paper, 17” x 23”, 2018

There is a real physicality to your paintings. The manner you lay down the paint, use of layered washes, heavy impasto, and mark making can feel aggressive and dirty to me at times. Can you offer insight into your approach? Where does the conceptual aspects intersect with the tactile process?

The paintings certainly are a mosh pit. A garbage heap. A junk closet. Paint slams against drawing. It obliterates the ground it rests on. And within its bounds, ideas rest, waiting for a viewer to bring them to life in their minds. Fragmented space, voids, and confusing perspectives not only support my conceptual framework, but also create and represent a break in the continuity of thought. My work is impulsive. It is reductive. It attempts to capture the viewer at a colloquial baseline in its imagery, and from there, the viewer can sink down into the image-as far as they are willing to go.

Kevin Blake, At the Wicket of Their Words Lay the Polish of Their Intention, oil on paper, 72” x 51.5”, 2017

A recent project Fair-Worded Instances of False…, though fascinating, this series has me scratching my head. There are recognizable scenes that are thrown upside down due to the insertion of seemingly disparate items and painting strategies that are often aligned with abstraction. You certainly make the viewer work. Do you employ any specific strategies when mapping out the 2-D space of the canvases? What’s the intent in this project?

Fair-Worded Instances of False Meaning was the title for a series of work that I showed different parts of in a couple of different venues in the past year. I want to say this work relates to fake news, as it sounds like it might, but it’s only tangentially related and an afterthought to the work. My intention here is to give the viewer a ride through their own memory and never say anything definitively. Never take a stand. Never be complete. Never be fully rendered. Never allowing the images to become the thing you want, or expect, it to be. I’m glad you’re scratching your head. I feel like that’s where I’m at too-scratching my head, wondering how the world appears the way it does. In the end, I hope what you see says more about you, than it does about me.

Kevin Blake, She Won Her Limp from His Husky Habits, oil on paper, 52” x 60”, 2018

What do you value most in your artistic practice?

I value the time I spend in my mind-thinking. This is an incredible luxury that isn’t lost on me. The more time I have to spend in that place, the less I become the focus of those thoughts. Sure, everyday my day starts with the bullshit that plagues the day, but I will eventually get to the bird’s eye view that the art allows me to have. It allows me to see myself from the outside/in.

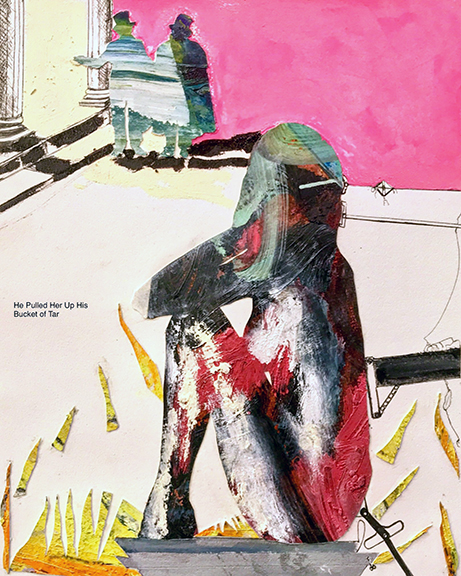

Kevin Blake, History’s Maws in the Moonlight, mixed media, 12” x 12”, 2018

Do you have any upcoming exhibitions or projects planned for the future? What’s the plan for the remainder of 2018?

I’m coming off a really busy year of exhibitions in 2017, and I’m happy to be settling back into a more typical working routine. There are irons in the fire. The birth of an option is just a day away, and until then I have a lot work to keep me busy!

For additional information on the paintings of Kevin Blake, please visit:

Kevin Blake – http://kevinblakeart.net/home.html

Riverside Art Center – http://www.riversideartscenter.com/kevin-blake-what-the-cool-pigeon-knows/

Bad at Sports – http://badatsports.com/author/kblake/

The Visualist – http://www.thevisualist.org/2018/02/kevin-blake-a-prosthetic-tongue-with-a-natural-curl/

Kevin Blake, artist, Chicago, IL, 2018

Artist Interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello