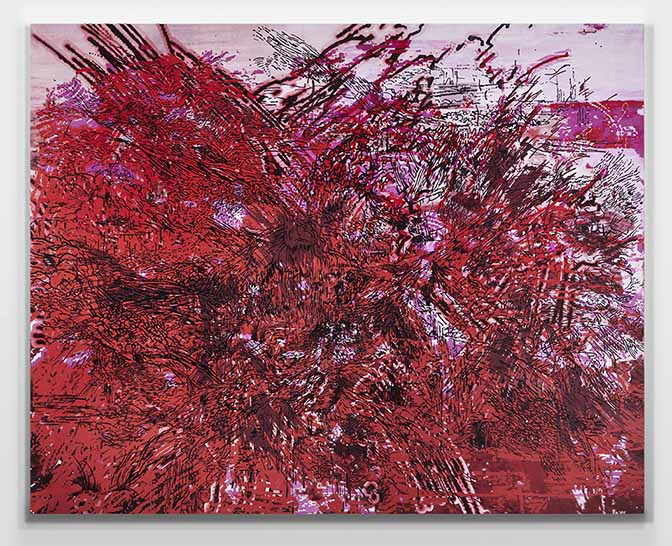

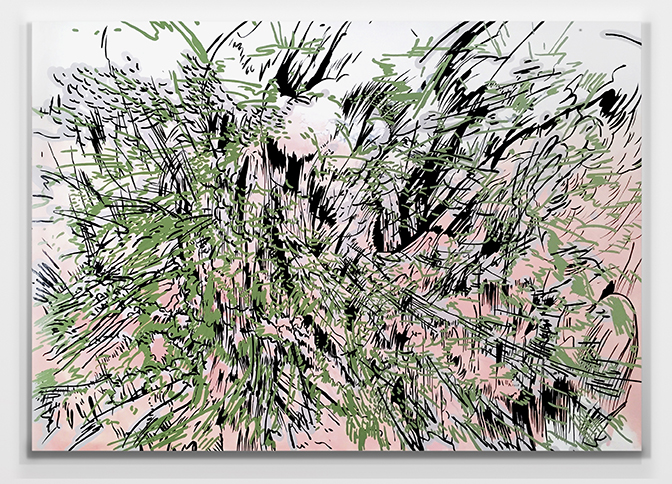

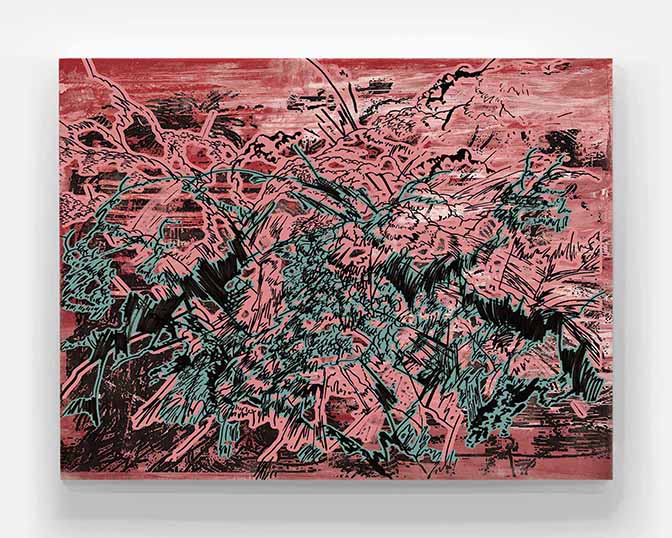

Working in isolation for roughly 20 years, Matthew Bandsuch has focused his studio practice on translating an understanding of carbon-based materials into visual representations. In this, Bandsuch works with foundations of drawing to create a long form series of works that takes on a physical manifestation through layering of mediums (graphite, renderings from carbon paper, and oil paint) in his investigations. The results are densely packed, stratified coloured fields that appear to be uncanny visceral places. This week The COMP Magazine traveled up to Palmer Square to discuss with Bandsuch his process, the hurdles of working in solitude, his affinity with past practitioners, and what he values most in his studio practice.

Can we hop back to your days in Detroit? I see this time as a precursor for that city’s current resurgence. Can you offer some thoughts on your late 1990s art making experience. Also, perhaps you can share with us an early experience or an individual you see as pivotal in your deciding to work as an artist.

The word I would use to describe making art in the 90s in Detroit is “open”. There was a lot of available space for art making and a tight knit and active community. We were always aware of what it meant to make art in Detroit at that time as well as what the city meant as a concept. There was no money to be made and you were free to explore new ideas. However, I didn’t want to make work specifically about my immediate surroundings because it felt unauthentic or I wasn’t able to represent it convincingly. But it has seeped into my later images.

You arrived in Chicago in 2001, I believe around 9/11. Did this event have an impact on how you had to rethink your art practice. How did you adapt?

I was in a show that opened a few days before the attack, so it was if that show never happened and I moved to Chicago about a week later. Other than the shock of the attack, it didn’t immediately influence my art, but it did affect my income and the amount of time I could spend on making art. I lost the circle of art friends by moving at that time which I think had a larger impact. I never replaced that group here so I have worked in a sort of isolation. I became a bike messenger for a short time for extra cash which was great way to learn about the city.

Can you discuss your interest in graphite. Specifically, in conversation you noted the contrast in diamonds to graphite. You did so when discussing the manner, you make lines. Please expand.

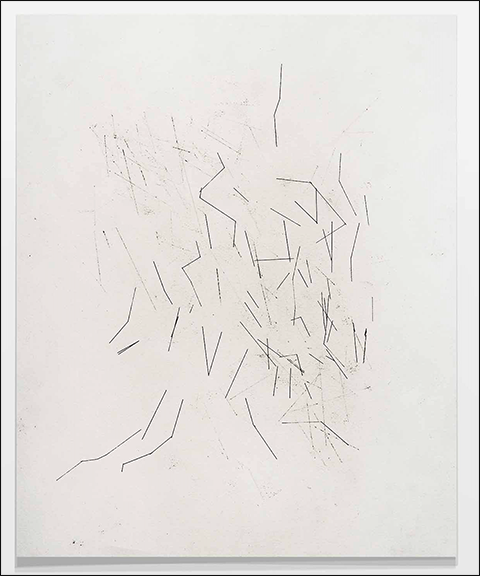

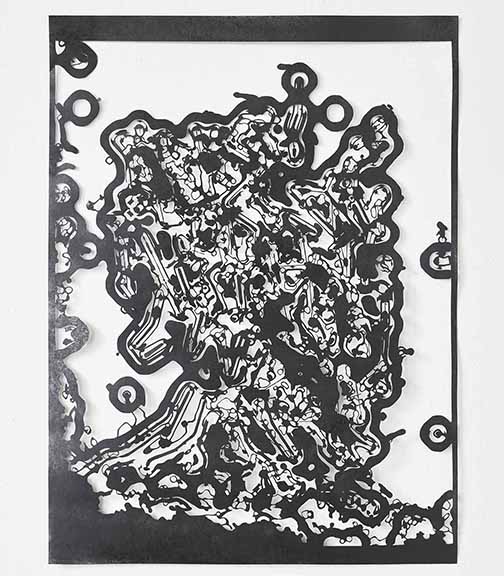

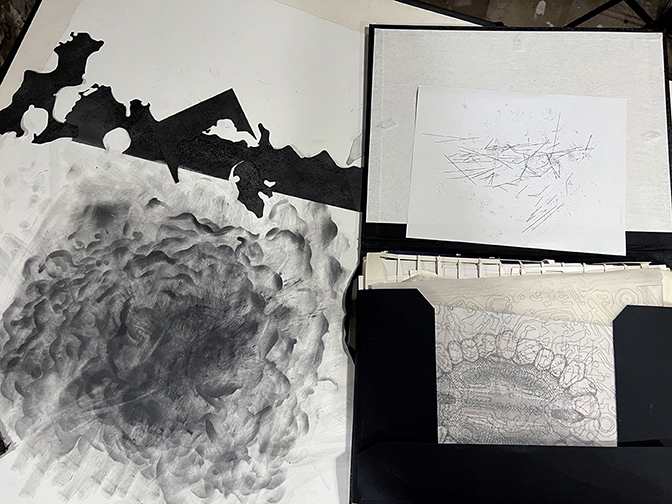

I wanted to change the direction of my work and was doing a lot of drawings. I thought that by being very reductive it would force a change in my thought process. Lines are the basic component of drawings they both connect and divide space. As an exercise I started making straight line drawings of faceted shapes which turned into blue carbon paper sculptures of diamond shapes. As a conceptual starting point I used Carbon forms drawing tools like pencil, graphite, or Indian ink. My piece “Rock” which is a paper and graphite model of a found piece of anthracite coal, a sort of “failed” diamond sibling, is the origin of the next series of work. I was interested in the idea of one piece creating or influencing the next to create a lineage, or generative structure. In each series, consecutive images contain pieces or remnants of the previous works including sketches, paint or results of other actions to create descendants.

Can you walk us through your studio practice. I’m interested in how you are tying the conceptual aspects to your mark making. One of the items I’m most drawn to is the translating of ideas while working with various materials, here graphite and paint.

I see the pieces as united in gesture or motion. The drawings have direction and flow into the paintings and that movement is what I try to pass into paint. The drawings act as reference or history for future works like blueprints. Drawings lay on top of each other.

Can you talk about the series “Pile”. This series appears to have been started around 2011-12. I see references to other early 20th century painters that take reference from early 20th century art movements like Futurism and Abstract Expressionism. What are you attempting to convey to the viewer?

I started all of this with the idea of cracking open a minimalist object represented by the diamond and the rock to see what was inside and push/pull it out. I wanted the imagery to be hermetic or isolated from popular culture and weave its own path. They have gradually evolved into unintentional landscapes, which is something I wasn’t interested in but, have followed the drawings directions. The images in the “Pile” series place layers of drawings on top of one another like farmland becoming industrial then collapsing into disarray or damaged by time or weather and so on. Stuff is layered and some of it falls apart but is scraped away for more to be piled on top. Some drawings are of places I’ve been to, some are disaster images found online. The removal of paint becomes as important as what stays visible. I sort of take the action of abstract expression and draw it to slow it down and freeze it. The repetition mimics the haystack series.

What do you value most in your studio practice?

Time to develop layers of imagery is most important. I make drawings almost every day. The mistakes, accidents and failures are what end up informing the progression. I paint over and over most of the them allowing some old parts to poke through. These do translate into sculptures, but I haven’t had much time to pursue this.

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Matthew Bandsuch, please visit:

Matthew Bandsuch – https://www.matthewbandsuch.com/index.php?

Matthew Bandsuch on Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/bandsuch/

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello