Meg Duguid is on an epic journey. Using performative practice as foundation while coupling traditional and new strategies of research and art-making, Duguid sifts through historical materials and applies fresh iterations that is often as transient as the roles she takes on in her investigations. The COMP Magazine recently visited her Little Village neighborhood studio to discuss her fascination with multiple strategies for documenting performance, the ephemeral nature of her work and why the Tramp still resinates today.

Can we start with your statement, “My work is about relationships – relationships between me and the viewer, a viewer and a video, a photograph of the viewer and the video”? There appears to be a sense of multiplicity in terms of interpretation occurring? Can you expand upon this statement?

So much of my work is about composing a moment and then figuring out how to create the best record or records of that moment or refiguring what was made in a moment into some new form. The irony is that there is no real way to accurately represent time, just aspects of it. So since representations of time are difficult, they therefore dictate the need for multiple experiences and contexts. I see each of these aspects of recording and making as a relationship, and it is a relationship that the viewer is also implicit in. This gets to the heart of my interest in performance and its relationship to documentation. I can document a piece in 17 ways at once and it will still not represent what actually occurred, so I choose to set a specific thing I want to leave behind after the action. Whatever it may be is just a new iteration/artwork of the ideas in the performance rather than a representation of the act itself.

Meg Duguid, Hole for Shaking Hands, 2012, drywall

Your practice appears to on one level divorce itself from creating or being fully satisfied with a static finished work of art. Is this a correct interpretation? Is your work continually ongoing or do you intentionally produce cyclic patterns that transform over time and present no set reading?

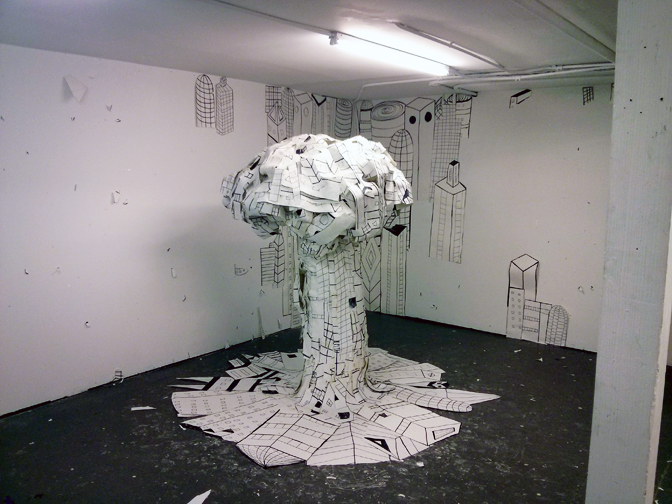

I think this is a very accurate read of how my process works. It’s entropic rather than static, so at any given time one thing may look complete but is likely just moving to its next phase. In a lot of ways I look at my work as threads of a blog, where each piece generates the next iteration. Since I am interested in relationships among performance, documentation, and exhibition practice, I inherently deal with the push and pull between the ephemeral experience and the need to make the ephemeral permanent through some form of documentation. This leads to the open-endedness where items such as ladders, Tyveck, suits, and suitcases just pop up on a regular basis. They are pieces that can be read both backwards and forwards in my art-making continuum. Sometimes this feels generative and other times it feels cannibalistic. I recently finished a show at the Mission where I made a papier-mache mushroom cloud from a paper city I installed on the walls. The piece was created over the run of the 5-week exhibition and documented as a part of the Tramp Project (see question number 5 for an explanation of the Tramp Project). I now have this mushroom cloud that I would like to cast in aluminum (if I can find the money). That feels like it will eventually be pretty permanent, whereas some pieces in my practice, such as the paper city used in the mushroom cloud which started out as part of the Bike Powered Analog Animation Machine and which was also exhibited as sculptures as a part of BAD curated by Larry Lee at Beverly Art Center in 2012, just get used and reused until they turn to dust.

Meg Duguid, Produced by Hole For Shaking Hands, 2013, drywall, wood, suitcases, Tyvek, automobile

Where do you draw your inspiration or sources? I noticed that there is an interest in cross-referencing performative practices with media that is considered traditional. Why have you chosen this format?

Performance art came out of visual practice; it was an extension of visual composition into action and movement. I think the traditional media has always been there for performance in both the genesis and the documentation of it, so really I am just treading its material history. In many ways I think about the way my practice functions in the way I think about Marcel Duchamp’s 3 Standard Stoppages. Each piece is a work unto itself, although it is connected to the next work and the one before. Each is a stop that is informed by the first shape. I also think of Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs, where each chair is both a representation of a chair and a chair itself. This gives me a lot of power where I become the Road Runner in a Wile E. Coyote flick. If I need a door, I can just draw it and it is a door.

Meg Duguid, Rider Negotiation, 2013, drywall, wood, suitcases, Tyvek, automobile

You appear to be fairly amused with laughter. Upon viewing and listening to “Laugh Tracks”, 2005, “The Great Guffaw”, 2001, and other works, I am wondering if you can describe the importance humor plays in your process?

I am amused with laughter. I have a love of the absurd which might manifest itself into things like packing walls into suitcases to reveal previous projects such as the series of pieces I did at Slow, Hole for Shaking Hands, where I cut a hole in the wall to shake hands through. A year later I came back to make Produced by Hole for Shaking Hands, where I removed the drywall from the studs and packed that same wall into suitcases, but left the area where the hole had been, leaving the previous work uncovered from the backside. During the run of the exhibit, I donned a Tyveck suit and took the suitcases home in a piece called Rider Negotiation. Someday I will complete another Rider Negotiation and use the drywall to make another wall.

Meg Duguid, Production of atomic credits, 2014, papier-mâché, sharpie, Tyveck

I find negotiating large objects also amusing. I am interested in what I find funny and incongruent, so what appears to be about humor, is actually my personal interests coming through. From those interests, I read and do research and find new in congruencies and structures to pull apart.

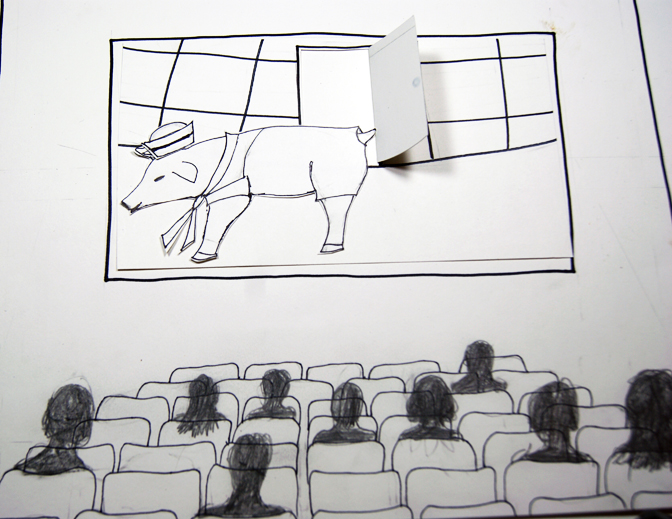

Meg Duguid, Preproduction of bomb explosion, 2014, paper cut stop animation still

You’re working on a film that interprets a lost screenplay that was created by James Agee for Charlie Chaplin. What piqued your interest in this seemingly dead work? Is there a title for your piece? Are you able to share the process you are currently developing for this project?

I first read the script in the back of a book and found it compelling, so I managed to option it. It was written for Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character by James Agee’s in 1947. Essentially I have been breaking the screenplay up into a series of performances, exhibitions, and installations that are or are related to the making of the film. At the end of this process I will have a short feature silent film that I would like to screen to multiple audiences while an experimental band plays a live score; the live score is then edited into the films, which are then rescreened to a new audience…

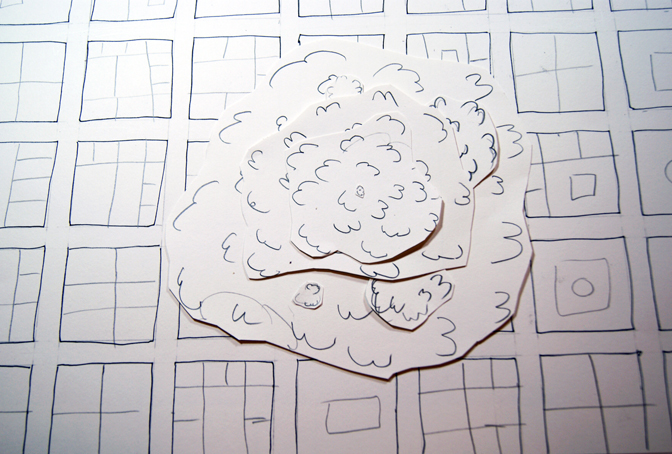

Meg Duguid, Preproduction of march of time, 2014, paper cut stop animation still

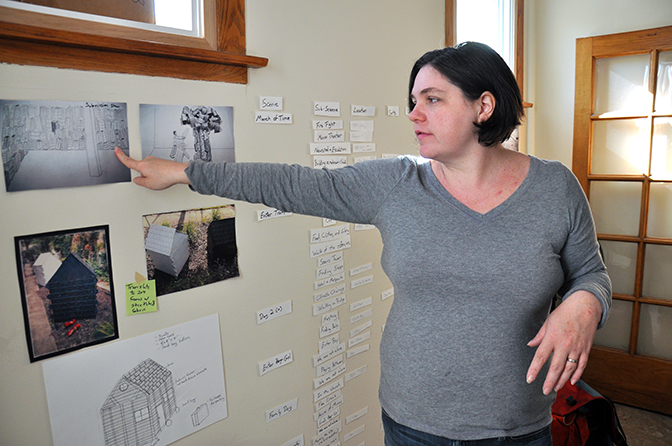

I am re-envisioning Chaplin’s classic character, the Tramp, as a female and have signed Meredith Miller to play the part. Just to give you a sense of how I am thinking about some of this, I have been creating stop-animation storyboards for the work since 2013 so I understand how all the parts should come together. Last summer I exhibited prototypes for the Tramp’s community at Terrain so I could get a sense of the look and feel of that set. I found that I did like the look, but when I am going to scale it up, I will stretch fabric over studs instead of using plywood. This will allow me to recycle the studs into other pieces when I am done and to fold my sets up and drop them in suitcases for traveling and storage.

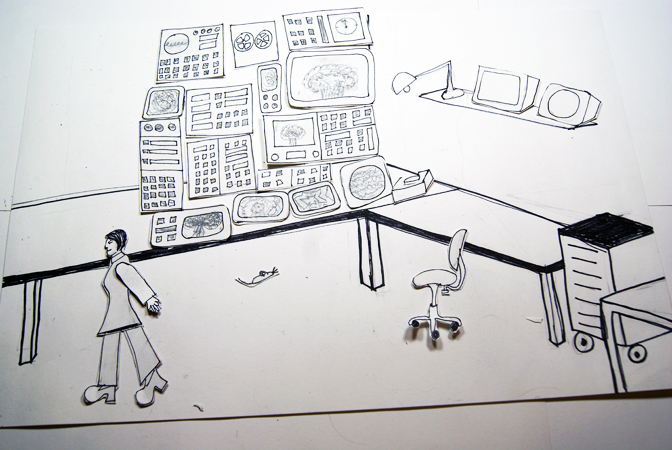

Meg Duguid, Preproduction of supercomputer love, 2014, paper cut stop animation still

I recently made some of the credits at the Mission with the mushroom cloud piece I talk about in #2. And At Slow, this February, I will be exhibiting all the storyboard animations that I created for the film, which will be displayed on 10–20 old monitors; this installation will later be re-installed in the film in the scientists’ underground lab as a part of the lab’s massive computer that tells the scientists what to do. Look out in the fall for a ton of performances in and around Chicago relating to this project.

Meg Duguid, Preproduction of bomb explosion, 2014, paper cut stop animation still

Also the narrative is amazing: It’s a post apocalyptic romp where a super-atomic bomb is dropped, leaving seemingly just one survivor, the Tramp. As the picture unfolds, it is clear that others have survived and are coalescing around two separate and completely different communities–the Tramp’s community, which is rebuilding a community by hand, and the community of scientists who created the technology for the bomb and who restore their technology and mechanized existence. For a majority of the film, the two communities are unaware that the other exists. Upon learning of the existence of each other, the Tramp’s community (but not the Tramp) is lured to the scientists’ way of life by the ease of technology. In the end, the Tramp, now alone, walks from this new world into the sunset.

Meg Duguid, Prototype for the Tramp’s community, 2014, plywood, paint, sharpie

Meg Duguid is not a painter, a photographer, a sculptor, or a performance artist; however, any of these handles might serve to describe her practice when necessary. Duguid has exhibited her work and performances at Defibrillator Performance Art Gallery (Chicago), Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), Central Park (New York), The Green Lantern Gallery (Chicago), Michelle O’Connor Gallery (San Francisco), DUMBO arts festival (Brooklyn) and numerous other venues. In 2015, Duguid will exhibit her work at Chicago’s Slow Gallery.

Additional work and updates on current projects by Meg Duguid can be seen at:

Meg Duguid: http://megduguid.com/home.html

Pre-production of atomic credits, 2014: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJec7s31wHM

Meg Duguid, artist, Chicago, IL, 2014

Interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello