The female experience has been largely overlooked throughout art history. As a society, we appear to be heading toward an era where the female voice appears to be gaining warranted attention. In the work of photographer, Melissa Ann Pinney, we are presented with an expansive look at the activities and rituals of girls and women with an intimacy and intelligence that can only be achieved through a first person understanding. This week The COMP Magazine caught up with Pinney to discuss her prolific career, her publishing efforts, her role as a mentor, and what she values most in her aesthetic practice.

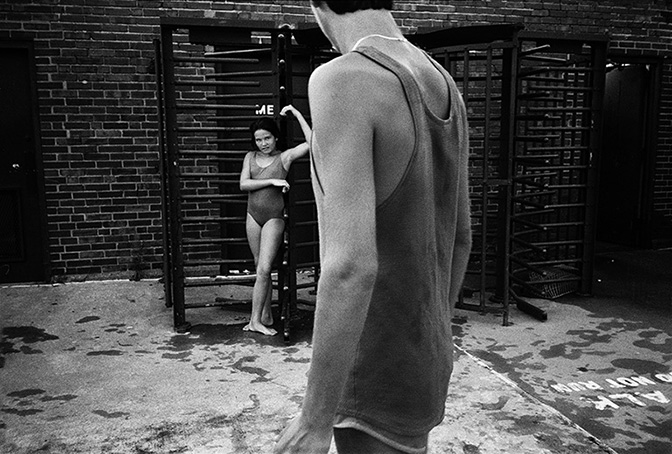

Melissa Ann Pinney, Hamlin Park Pool, 1984

You’ve had a fairly extensive and remarkable career. I’m wandering if we can rewind a bit and discuss early influences. I noticed that you have found inspiration in the work of Dorothea Lange, Robert Frank, Julia Margaret Cameron and others. Can you identify any specific item or method that piqued your interest in their work? To what degree do you see their practice having influence upon your approach to making photographs?

My parents were great readers and lovers of music. My mother made dresses for the three girls in our family and took wonderful photographs with her Brownie camera, but neither parent knew much about art or artists. Growing up Catholic, my early art education was in the iconography of Christian religious paintings and the color symbolism of the Church calendar.

I had five brothers and an over-bearing father who didn’t expect much of his daughters beyond looking pretty and being so-called nice girls. I wanted to do everything the boys could do – better. Yet female protagonists were few to girls of my generation, and accounts of women artists simply not available. Oppressed by the patriarchal norms at home, at school and at church, I found accounts of young women whose rich and ardent inner lives became beacons for my own budding life as an artist in readings from

The Lives of the Saints.

In the lone art history assignment I remember from my all-girls high school, I researched Picasso’s Guernica. That was when I understood that art was a language – of color, shape and symbol, both universal and particular to each individual artist. I was captivated, but had yet to discover a medium in which to make my own art.

In the bookstore at Manhattanville College in Purchase, NY, I found photography books from the Museum of Modern Art. Dorothea Lange’s WPA images and a paperback copy of the Americans (only $5.95!) showed me how one could make powerful art from the circumstances of ordinary, secular life. I learned that a series of photographs well sequenced accumulates meaning well beyond the single frame. It wasn’t until graduate school at University of Illinois, Chicago, that this was reflected in a series I made at Chicago’s Hamlin Park Pool on the north side. My early B/W portraits of young women in Chicago interiors were very much influenced by Julia Margaret Cameron.

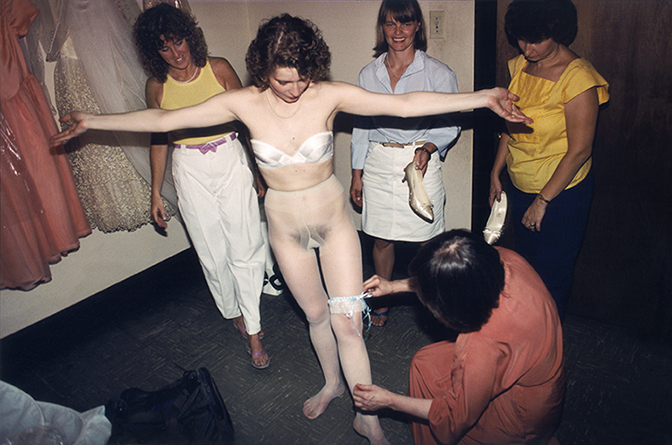

Melissa Ann Pinney, Mother and Attendants Dressing the Bride, 1985

I frequently share your work with many of my students. Often, a number of them have found your initial monograph Regarding Emma: Photographs of American Women and Girls (2003) an entry point and validation to look closer to home when pursuing their own work. Can you speak to the relevance of this type of material? What prompted your investigation?

It’s interesting how the title, Regarding Emma, became misleading in ways I didn’t intend or foresee. Because of that title, many people assumed that my daughter, Emma, was the girl in most of the pictures. In fact, most of the pictures are not personal and were made long before Emma was born, as part of my Feminine Identity series. Taking the wedding ritual as a starting point, the Feminine Identity series looked ahead to older women, then back to girlhood to see how our dreams and expectations of women are made visible; how feminine identity is constructed, taught and communicated between mothers and daughters. These pictures, made at baby showers, weddings, parties and beauty salons, seem the most overtly political of my images to me today.

When Emma was born I began to photograph her, thinking of the pictures as a separate project. Photographing my own daughter and our family life allowed me to understand the construction of feminine identity from the inside. It became clear that at the heart of both projects are images of girlhood, comprising one series, not two. My understanding inevitably grew, as I did, from being a daughter to becoming a mother. Many photographers have photographed their families; what is unique in my work is the way in which the pictures of my daughter and family life swirl out to include the community in a larger social narrative of identity and experience.

Melissa Ann Pinney, Bat Mitzvah Dance, 1991

I find your 2nd monograph, Girl Ascending (2010) rather timely when considering the current cultural shifts occurring in America. Specifically, I’m fascinated with how you have portrayed distinct female rituals that continue to be maintained in a time where many societal foundations are brought into question. For me, time appears to play an instrumental part in this series. I’m wondering how you consider your work in contrast to the times in which it is made and how it portrays our current cultural milieu?

Girl Ascending chronicles the play and social rituals of girls ages nine to seventeen. My work has always been feminist. By that I mean that my primary concern has been the depiction of women with agency, women as subjects of their own lives. I’ve tried to honor the complexities and depth of our experience and explore the often neglected connections between girls and women. For example, very few girls of my generation played sports. My daughter’s generation almost all enjoyed the camaraderie of team sports, from their first soccer team at six years old through college.

Girl Ascending was published in 2010 – so much has changed in our society over these eight years! In 2010, I understood gender to be binary. I didn’t know any girls who had come out yet– that happened later, when they left home and got to college. We weren’t talking much about LGBTQ rights or pervasive sexual harrassment. Some things improved dramatically although we are still (still!) seeing women through the male gaze in art and in film. I’m glad to know that young people relate to my work, many of whom have felt pushed into rigid gender roles growing up and see their experience mirrored in my photographs. The cultural issues I grapple with at any given time can’t help but be reflected in my pictures, made as they are, from attentive observation of the world. Issues don’t drive my picture-making directly or literally– or even intentionally. What I find in the world is more mysterious, rich and surprising than anything I can imagine. Learning from the pictures I’ve made comes first and I’ve found it to be more productive than starting with a concept.

Melissa Ann Pinney, Team Evanston, 2005

What do you value most in your photographic practice?

I am undyingly grateful to have a vocation that’s sustained my interest and challenged me now for forty years. Maybe it’s growing up with all those siblings – I’ve always wanted something of my own, something that couldn’t be taken away by change or chance. In making photographs I’ve looked for the transcendence and independence that intrigued me as a girl in the lives of the saints. In photographing I’ve found a way to be fully present and engaged with life as it unfolds. I’ve become part of a community with shared values and have tried to help other artists along their way.

Melissa Ann Pinney, Balloons, 2004

In looking at a more recent publication, Two (2015) that you worked upon with New York Times bestselling author Ann Patchett, I see tenets relating to a number of ideas: partnership, duality, common experience, and shared identity. In addition to the photographs, there are 10 writer contributions. The images appear to be taken from various pursuits. These materials read differently than previous projects. What prompted you to focus upon this subject matter? How did you compile the photographs? How did the process differ from other endeavors?

Yes, TWO was a different kind of book in it’s mix of images and text about the notion of two, rather than a monograph. It came about organically. I shoot a lot of images and work best when I’m responding to what’s around me rather than to a preconceived idea. After Girl Ascending, I decided to print every image that interested me from the last several years, without regard to subject or sequence, just to see what was there. Surprisingly, what I ended up with was a couple hundred images that contained two people or objects. Within that found structure are themes I’ve been exploring for years: mothers and daughters, sexual identity, relationships, a sense of place, aging and race. There are eleven short discrete sequences of related photographs in TWO and ten essays by contemporary authors such as Jane Hamilton, Ruchard Russo, Barbara Kingsolver and Elizabeth Gilbert.

Ann Patchet became my friend when she wrote an introduction for Regarding Emma in 2003. On a visit four years ago Ann was struck by all the work of two’s up in my studio. TWO was Ann’s idea, and it was her connections to the other writers that launched the project. Ann is also a bookseller– she wanted a way to get my work out to an audience beyond the photo book world.

Melissa Ann Pinney, Earlene & Son, from TWO, 2013

You have taught for a number of years in the Department of Photography at Columbia College Chicago. While I was a student (back in the 1990s), you had the reputation for being rigorous, yet compassionate. I’m curious if there are any long-standing items you regularly share with your students?

I hope my students will discover the richness I’ve found in photography for themselves. I work to inspire by showing lots of different work by diverse photographers from all over the world. I push my students to do the maximum rather than the minimum – that’s where the rewards lie. Inspiration comes by doing, not by sitting around and waiting for it. There are so many photographers competing for shows, for jobs, fellowships and book deals. Who will care about your work if you don’t care enough to do your best? It can be hard to put together a life in photography. I’ve taught one class a semester for years while also doing editorial assignments for the New York Times Magazine, Marie Claire, and Oprah Magazine, among others. I’ve taken portrait, event and wedding photography assignments from early on. The trick is to get hired because the client likes the work you’re already doing for yourself. I believe that people and opportunities present themselves to those who work whole-heartedly – which doesn’t mean you don’t have to make every effort to connect with others in the field!

Melissa Ann Pinney, Ho’okipa, Maui, 2016

I see that 2018 looks to be a busy year. You are preparing for solo exhibitions in Chicago, and Maui, and a group show in Los Angeles. I’m wandering if you can share with us your plans for these exhibitions? Are there any other projects on the horizon for the New Year?

I’m excited about my solo exhibition, Girl Transcendent, coming up in June at the Schaefer International Gallery of the Maui Arts and Cultural Center. My work is included in the exhibition Not an Ostrich: And Other Images from America’s Library at the Annenberg Space for Photography from April 21, 2018 through September 9, 2018. The exhibit is the result of celebrated American photography curator Anne Wilkes Tucker’s excavation of nearly 500 images—out of a collection of over 14 million — permanently housed at the Library of Congress. I’ll have a solo show at Schneider Gallery in the fall.

2018 will be a year of editing several long-term (as yet untitled) projects for publication. One is a father-daughter project: I’ve photographed my husband, Roger, and our daughter together since Emma was born in 1995. My other project consists of work I’ve made on Maui for over 20 years, both beach and town.

Melissa Ann Pinney, Julia, Maui, 2017

For additional information on the work of Melissa Ann Pinney, please visit:

Melissa Ann Pinney – http://www.melissaannpinney.com/

Art Institute of Chicago – http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/artist/Pinney%2C+Melissa+Ann

Chicago Magazine – http://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/April-2015/Pas-de-Deux/#/0

Chicago Tribune – http://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/books/ct-books-0129-girl-ascending-20110128-story.html

Museum of Contemporary Photography Chicago – http://www.mocp.org/collection/mpp/past/pinney_melissa_ann.php

Additional photographs by Melissa Ann Pinney:

Melissa Ann Pinney, The Real, Live Barbie at Target, 1998

Melissa Ann Pinney, Disney World, 1999

Melissa Ann Pinney, Ballroom Dance, 2008

Melissa Ann Pinney, Lake Michigan, 2009

Mellissa A. Pinney, photographer, Evanston, Illinois, 2015

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello