One of the most remarkable times to make art is in youth. An undefinable raw freedom and fluid yet erratic approach can give rise to something unknown, potentially something the audience (and artist) struggles to identify by name. In the seemingly disjointed visual vocabulary of Milo Christie there appears to be a fresh-faced attempt to explore this type of terrain. This is a daunting task, but Christie appears to be game. This week the COMP Magazine jumped on the CTA and headed up to Palmer Square to discuss with Christie his circuitous childhood experiences, the series Minotaur Videogames, his interest in independent curation, and how the public domain (parks, alleyways, back lots) is an ideal format for sharing artwork and experimenting with new ideas.

Your energy (and fearlessness) is refreshing. You are at the outset of your journey as an artist. Can we back up just a bit? Perhaps, you can discuss life prior to studying at SAIC (The School of the Art Institute of Chicago). You spent time in Europe and out west in California. Can you note any specific items or people that prompted your current focus on the arts?

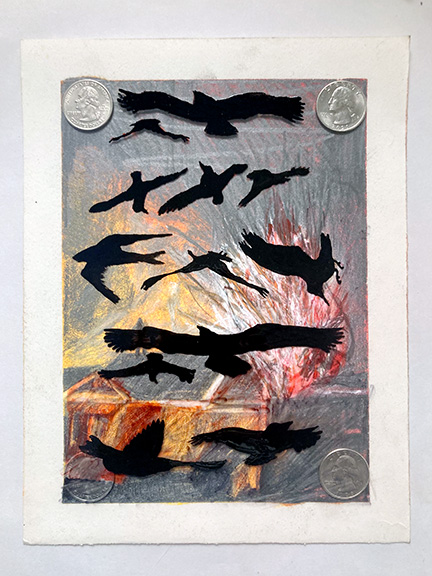

I was born in Berkeley, California, and lived in El Cerrito until I was around 3. My family then moved to Berlin, where we were for the next 5 years. My parents tell me that I was taken in a stroller to the Hamburger Bahnhof and saw Joseph Beuys’ works in their permanent collection, which I don’t remember at all, but which I like to credit as the first encounter with what is currently becoming my life. In 2008 we then moved to London, where I ‘grew up’ so to speak, and at around 16 or so picked making art over studying music or maths, which are the alternate paths I might have taken. From 2011 to 2018 we lived quite close to the Tate Britain, and I spent a lot of time there – there are definitely shows that I remember well, such as John Martin’s paintings of the Apocalypse, a show called ‘Ruin Lust’ whose accompanying monograph I still look at; Rachel Whiteread also had a retrospective there which was incredible, and the Turner prize shows that were also eye-opening (maybe Michael Dean’s piles of pennies somehow wormed its way into my brain now that I frequently use quarters in my work…). The other big, big show in my memory (which solidified him as one of my favourite painters ever) was Anselm Kiefer’s Walhalla at White Cube Bermondsey, where he had these colossal paintings with molten metal poured onto them, and specifically this one room that was filled with lead boxes, manila folders, reels of film spilling out and onto the floor… Then I left, and haven’t been back in 4+ years.

When interviewing artists in youth I’m most interested in the idea(s) that prompted their decision to be a creative. There’s been wide response, but the most common idea often rests in their interest in defining their generation’s visual vocabulary. At outset, what do you see as your ‘prompt’ for being an artist? Do you see any recurring themes with your peers?

I don’t necessarily care too much about a cohesive generational vocabulary – I primarily make work for myself and to share with my friends. However, I definitely feel like the agency that working in creative fields affords me was a big draw when I started – you’re really only accountable to yourself, and you can set your own boundaries (((((((within reason))))))).

I’m curious about the series Minotaur Videogames. Me, a games (TCG & Video) addict. I’m wondering if you could walk us through this series of work produced in 2020.

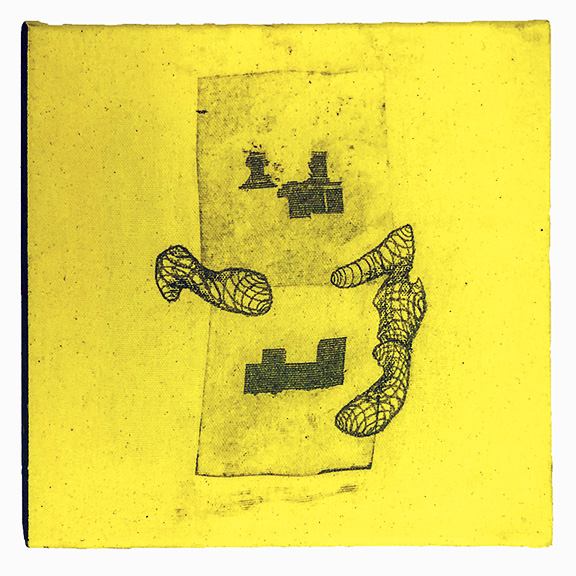

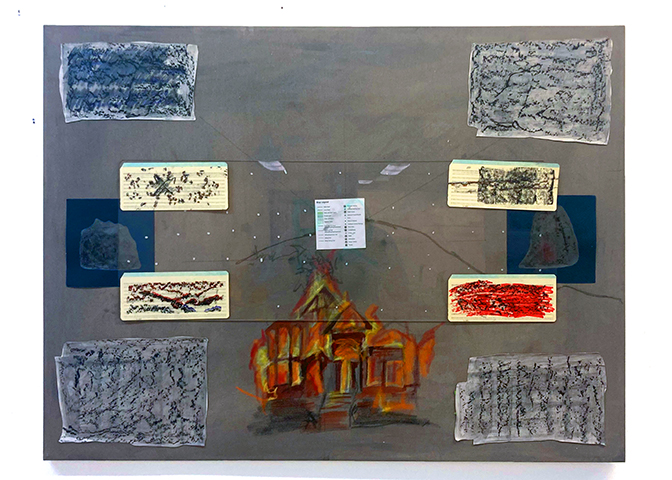

Minotaur Videogames is a name I gave kind of retrospectively – the first 4 yellow paintings were titled minotaur videogame I-IV, and then I made more work in that vein, and then the group as a whole is just called Minotaur Videogames, because they all have this style of making a 3D-mesh-like form. That form is effectively just the result of a specific set of rules that I use to draw it – draw a kind of bulbous closed shape, pick a point on its border, then draw concentric curves emanating from that point inside the shape. To me, it ends up looking like a 3D model, and it definitely started as a doodle in page margins.

I think the Minotaur aspect of the name came from House of Leaves, which I was reading at the time, but I’m not sure. That book features an ever-expanding labyrinthine house in one of its sub-stories, which to me is related to the generic internet/video game trope of ‘the backrooms’, the place you go when you no-clip out of reality: to that end I felt that drawing pseudo-volumetric forms with no background or sense of depth outside of them placed them in that kind of extra-real space. Still, they were definitely just doodles at heart.

I’ve invested much studio time and research in looking at and making work for the public domain. I see these acts holding a bit of randomness and freedom. In recent time, you’ve been presenting works in environments that frequently inhabit vacant lots, obscure spaces, and parks. Can you discuss this effort and what you see as being the intent or outcome?

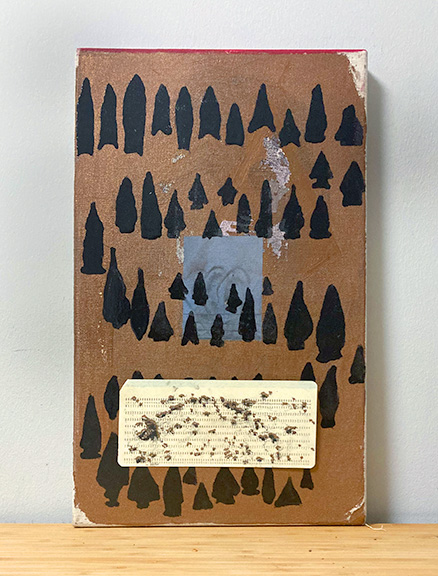

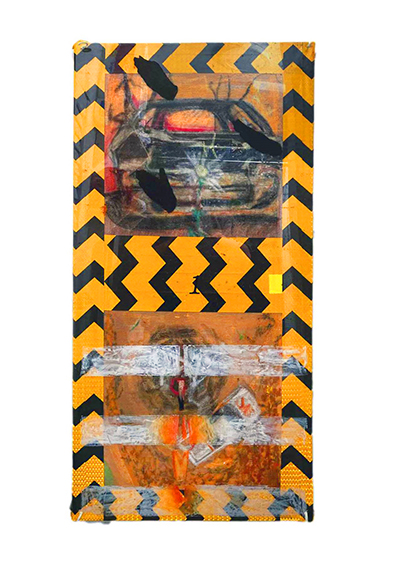

This is a new thing for me, at least contextualizing as part of my practice proper and not just the result of passing time on road trips and stacking a bunch of junk on top of itself. The most recent was ‘disembrainings’ which I thought was a great word for what might happen in a particularly gruesome car crash, or what happens to the daughter in ‘Hereditary’, and so the three paintings are mounted to a signpost and use retroreflective tape to vaguely act like road signs, but also to find a way to put painting in space in a different way. I think it is a natural progression from some of the imagery I have been using over the past year or so, of forest fires, of burning homes, burning wind turbines, more texturally abrasive works, to then placing or integrating the works in these spaces.

There’s also a connection for me with archaeology, and maybe geocaching. One piece I don’t know if I ever documented, or the photos are lost in some hard drive somewhere, of a fake floorplan of some sort of building (in the vein of the roman houses they find under London, only a few bricks high, but with rooms delineated) in a vacant lot on Pershing and Normal in the summer of 2019. I don’t know if it’s still there, but I think they patched over the way you could get into the lot from the rail bridge.

This also plays into a larger conversation about documentation – if this work isn’t permanent in its vacant lot, what is that lot but a backdrop for taking photos of the work? Why is that important? Are you simply trying to amp up some aesthetic quality of the work? For ‘disembrainings’, this was partially the case, because where do you find road signs? Outside; however, as is similar with other work that I have documented, I would love to have them be presented in that space as part of a show, kind of like the show in the basement of P.P.O.W., or Art Lot, or Plague Office in Kazan, Russia.

What do you value most in your studio practice?

At least for me, a large underlying motive or search within my practice is to better understand things about myself and my values or taste that may be very difficult to verbalize at first, or that I don’t know yet. I feel like we all act on a set of complex predispositions that are at outset unknown to us; Knowledge of or intimacy with those can make us more confident in our output. What is actually important to you? How are you going to find that out? I can’t speak for anyone else, but those questions are a large driver of why I make work.

Can you tell us about what you are currently working upon? Do you have any upcoming exhibitions? What are some items you hope to accomplish or investigate in 2023?

I am working on a large amount of floor objects, and also trying to be more intuitive in my judgement of ‘what is good’, ‘when do I stop’ etc. I will be in a show with Switch Hook Projects in a Chiropractor’s office, and maybe some other stuff that isn’t quite confirmed, but mainly a lot of my time is taken up putting on shows at my space, Weatherproof.

For additional information on the aesthetic practice of Milo Christie, please visit:

Milo Christie – https://milo.house/home.html

Kiki & Bouba – https://www.kikiandbouba.gallery/product/vyv-exif-2

Milo Christie on Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/father_john_christy/?hl=en

Artist interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello