Moholy-Nagy: Future Present

September 30, 2016 through January 3, 2017

The Art Institute of Chicago

Regenstein Hall

111 South Michigan Avenue

Chicago, IL 60603

László Moholy-Nagy. A 19, 1927. Hattula Moholy-Nagy, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

© 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

When I was first introduced to László Moholy-Nagy in the late 1980s I struggled to get my mind around the theories he explored and his use of nontraditional materials. In my youth, the absence of direct narrative elements and the testing of unfamiliar terrain created a chasm between my limited understanding of the arts and the modes of intellectual inquiry being implemented by this artist. Initially dismissing the work, it was not until graduate studies that I was required to thoroughly consider and apply his ideas in a series of drawings and photographs encouraged by Bob Thall in the Department of Photography at Columbia College Chicago. In the series “(IR)rational Movements with the Camera” I setup parameters similar to a scientific-based experiment informed by the light box project that Nathan Lerner (one of Moholy’s students) employed while teaching at the Institute of Design. I did not fully realize the impact this early encounter would have upon my ongoing investigations until a recent visit to view the Moholy-Nagy: Future Present exhibition currently at the Art Institute of Chicago.

László Moholy-Nagy. Raum der Gegenwart (Room of the Present), constructed 2009 from plans and other documentation dated 1930. Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 2953. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) was a consummate artist and educator who’s output covered advertising, film, painting, photography, product design, sculpture, and theater sets. In addition, Moholy was a prolific writer, theorist, and produced a number of seminal books (e.g., Malerei, Photographie, Film “Painting, photography, film”, 1925) and writings addressing the intersection of the fine arts, new technology, and modern culture.

Born László Weisz in Hungry of Jewish decent, Moholy established his reputation at the Bauhaus art school in Germany (1923-1928). In 1937, due to political upheaval in Europe he eventually settled in Chicago and founded the New Bauhaus (now the Institute of Design) in a Prairie Avenue mansion designed by architect, Richard Morris Hunt, for department store magnet Marshall Field. Without doubt, this long overdue survey of more than 300 works clearly indicates that Moholy was not only ahead of his time, but the quintessential Renaissance Man of the modern era.

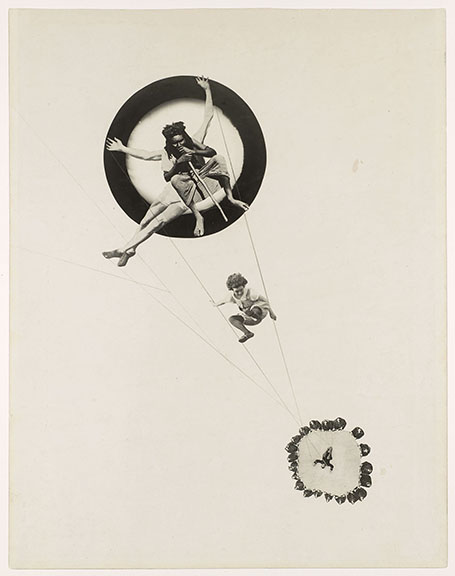

László Moholy-Nagy. Behind the Back of the Gods, 1928. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987, 1987.1100.23. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

For some, the content will cause pause. Even in our contemporary milieu, Moholy’s ideas and output can appear somewhat nebulous and difficult to comprehend. As a society, we still struggle to assess, contemplate, and describe the simplest forms of thought and tactile visuals. Nevertheless, through this comprehensively organized survey by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (NYC), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago, one encounters an exhibition design that deftly mirrors and succinctly outlines Moholy’s modernist aesthetic. This is achieved via a deliberate exhibition layout that traverses a career from painter to photographer to designer to commercial artist to theoritician, and culminating in his educational treatise. The arrangement comes full circle, and therefore reflects Moholy’s belief that art should echo the time in which the artwork was made through examining ideas and materials current with the present day. His application continues to be seen through the legion of educators and practitioners who have gone on to create and teach in his spirit.

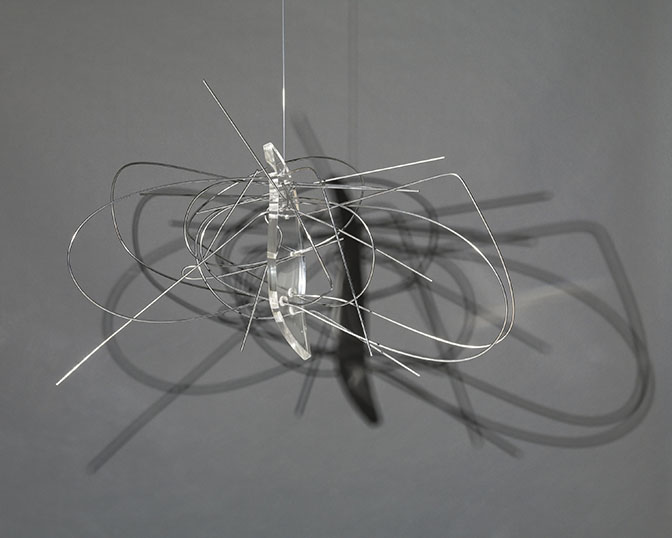

László Moholy-Nagy. Dual Form with Chromium Rods, 1946. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, 48.1149. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Earlier this month, I returned to view Moholy-Nagy: Future Present. This time with students in tow, I found the experience curiously enlightening. Many of the questions I posed to myself almost 30 years ago resurfaced. My students were much more patient and receptive in assessing Moholy. Bouncing around the galleries, we discussed how Moholy’s use of formal elements differed from his predecessors, the idea of using technology to create an utopian society, and how Moholy’s practice is still relevant in today’s digital age. Their interest and ability to digest the material was inspiring. In the final gallery, we spent a great deal of time reading the wall text that summarized Moholy’s thoughts contrasted by artworks produced by the artist and his students. I sensed a moment of passing on the torch. The cyclic nature of this experience gave rise to future projections and dialogues we can revisit in their studies. This exchange was perhaps one of my most cherished teaching experiences to date.

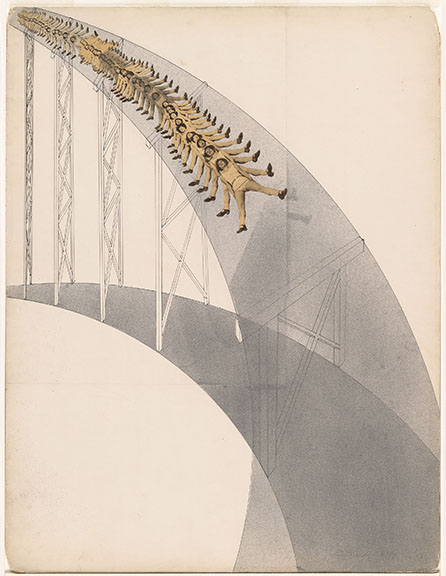

László Moholy-Nagy. Rutschbahn (Slide), 1923. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, 19.1965. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

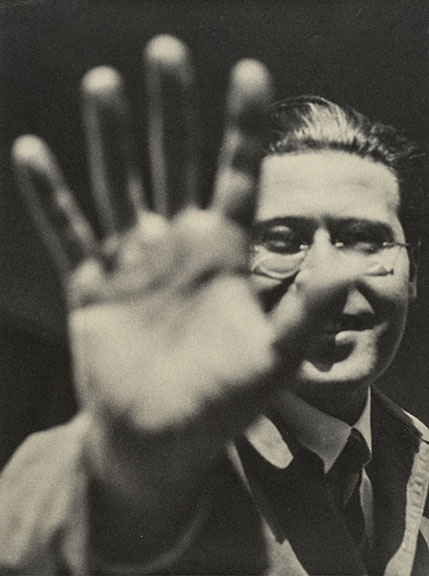

In reflection, I’m most fascinated by Moholy’s statement, “The illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant of the use of the camera as well as the pen.” This prophetic, yet freightening comment appears to have become a part of our daily life. We now, as a culture, view more images than any time in the history of humankind. The transformation of technology, image production, and decemination has continued to shift our means for understanding and interacting with eachother. In viewing Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, one will surely cultivate a more clear understanding of the importance of taking time to look at the world from varied perspectives, utilize these opportunities, and continue to hold hope for the future.

László Moholy-Nagy. Photograph (Self-Portrait with Hand), 1925/29, printed 1940/49. Galerie Berinson, Berlin. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Review by Chester Alamo-Costello