Paul Hopkin established Slow (Gallery) in 2009 in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois, as an alternative venue for presenting innovative new art by regional, national and international artists. The space is not quite an apartment gallery, nor commercial space. Hopkin presents artworks that can be seen as challenging and thoughtful requiring the viewer to take time and contemplate.

You have a remarkable background. Born out west, attended Brigham Young University, then the School of the Art Institute, lived briefly in Germany and now reside, work as an artist and direct one of the more challenging art spaces in Chicago. Can you expand on this summary? Has your background informed your artistic and curatorial practice?

I do have a remarkable background, but it didn’t seem so growing up. It was small time and I was always aware of that. It was all I knew, too.

I was raised with profound contradictions beginning with my father. He was a staunch and strictly practicing Mormon. If you don’t know, Mormons are among the most conservative Americans. Utah Valley, the cultural center of the Mormon kingdom, is and has long been the most conservative Republican voting district in the States. My father was a fiscally liberal and rather vocal democrat.

Installation view from Special Gentlemen’s Time with Paul Hopkin, watercolor drawings and custom scaffolding, high fire makgeolli cups, 2014

I was born in the shadow of the military. My hometown is the practice field for the Air Force Thunderbirds. I have seen them fly thousands of times. I sat in the cockpit of one of those jets at least three different times. My junior year of high school began witnessing four pilots flying in formation straight into the desert pavement to their deaths.

The military brought an outrageous gender problem to my hometown. There were 120 students in my high school grades 7 through 12 and 400 single GI’s stationed in the town. The school is part of Clark County school district—the same as Vegas. It was a huge school district. By the time I was nearing graduation, it was becoming common practice to keep pregnant teens from dropping out by sending them to my school. My graduating class had 24 students. 12 girls? 4 were pregnant.

I was raised with 3 brothers and a sister. Throw in a foster sister for 2 years for good measure. I visited aunts and uncles and grandparents often. Our family was dutiful, religious, upstanding and stable. My town was transient. Few of my peers had two parents. Many of my friends would stay at my house to avoid a drunken father who was notoriously mean when drunk. The major employers were the military and government sub-contractors. Many families were there during a gravy job in an up and down job history. The military folks were commonly transferred. The other folks were all hired on soft money, so unemployment was more common than averages indicate.

The dynamics of my home environment set me up to experience parts of life that are not as they appear. I was encouraged to question assumptions and to dig into ideas. My father taught my brothers and me to argue following the rules of debate. Contradiction and paradox are my native language.

No one knows the nuances of my history. How could they possibly? But that history generates a point of view as distinctive as the sources. Identity politics was demanded of me when I was a student. I try to set students up to exceed that very limited point of view with a refrain: “your demographic is not your identity.” In my curatorial practice I tend toward artists who embrace complex thinking. I am drawn to a kind of density. Sometimes that works best when it is visually simple but dense in thinking. There is almost always a kind of mess in the work I am drawn to.

So is Paul Hopkin really slow? There was a recent exhibition that could imply this and the name of your gallery is Slow. Can you enlighten us with your fascination with slow?

When I refer to myself as slow, stupidity is only a part of that. I did read a book that has been hugely influential in my life, Stupidity by Avital Ronnell. My first impulse toward the name is artwork that takes a while to navigate. I think that making art is a lousy way to demonstrate that you’re smart. When art is too theoretically based it tends to stem from a kind of insecurity—the artist is not confident enough to put stuff out into the world without propping it up on something already recognized or part of the cannon.

Installation view from Special Gentlemen’s Time with Paul Hopkin, watercolor drawings and custom scaffolding, high fire makgeolli cups, 2014

Another kind of slow is the age of artists I show. The art world, and maybe Chicago is worse about this than other cities, is obsessed with the new young thing. Though it is a great place to cut exhibition teeth, Chicago is a town that is less kind to its mid-career artists. More that half the folks I work with are my contemporaries-we’ve been around for a while. We’re middle aged but making fresh, current stuff.

I believe making art is much like braising meat—the slow development process deepens nuance and (again) complexity.

In conversation you’ve describe the running of Slow as an extension of your practice. How does this function? Is there a culmination or endpoint, like when one completes an artwork or can this be seen as an ephemeral gesture?

My father comes from the cowboy tradition of storytelling. I grew up following him around. It was a way of being. There was a system that indicated social ranking—the elder statesmen held the floor longest. Cowboys pride themselves on that strong and silent thing. Stories are edited, directed toward punch line, refer to shared knowledge without explanation. Women rarely told stories in the presence of men. As an adolescent I spent hours with my grandmother holding court with visitors and aunts. The women were accustomed to my presence and so carried on as if I were only a child playing nearby.

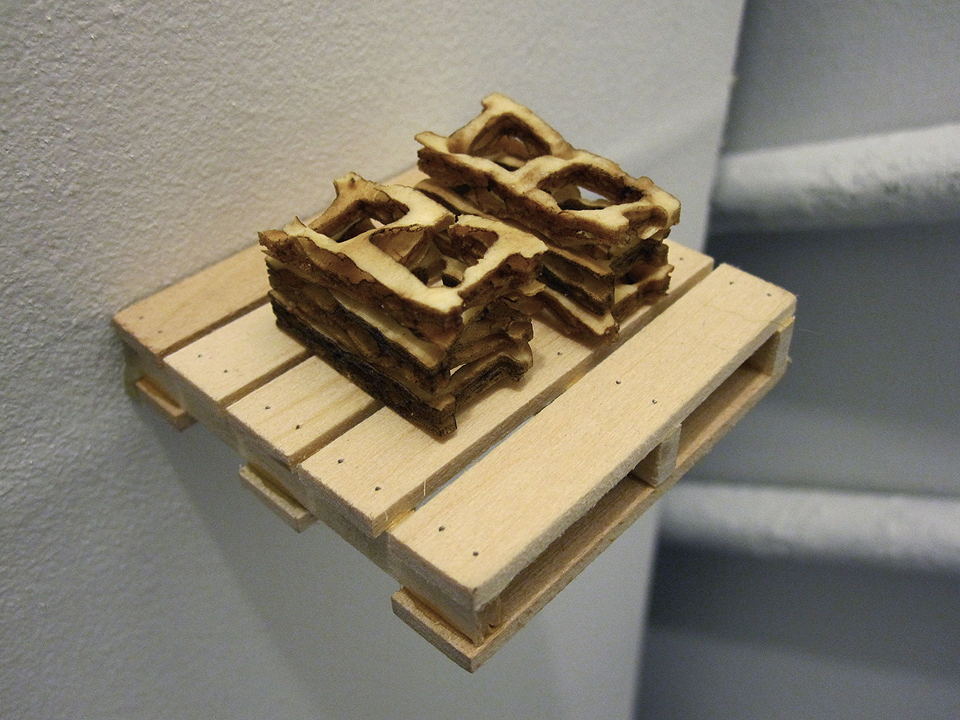

Paul Hopkin, Cracker, 2009

I was raised to become a storyteller. One of my approaches was to observe what people accepted, and make my work seem like it fitted into that acceptable range at least on the surface. That shift became much more important during graduate school as narrative art was not accepted in the environment. I had to edit my work in a way that its primary appearance did not read as narrative.

My background was colorful and interesting to faculty. I began to have problems with focus during critique. Faculty wanted to hear more of my stories at the expense of discussing the work. I swapped my personal history for the Wizard of Oz. I figured that if I structured the work around familiar narratives wouldn’t have to repeat the background as much. It worked for a good long run, but at some point it became its own problem. I became that Wizard of Oz artist, so I switched it up again.

I began teaching sometime near that transition. It wasn’t ever that I thought that teaching was a part of my art practice so much as the recognition that I was engaging a lot of people in my ideas through teaching. I spent a lot of energy learning how to teach and let my studio practice wane. It was a way of exploring my foundational hierarchy—which was important to me, the ideas, the narrative, representation, etc. I love teaching, but it is clear to me that the visualization, the physicality of material, plays a role outside the support of an idea.

The gallery started as a response to buying a building. I asked myself what I could do in my own place that was different from a rental. That led to a mixed use space which led to the rest. Putting shows together is another way for me to think through the visual world. I ask myself questions about ideas, context, and my own priorities. Working with other people shifts and sharpens the ways I see. I didn’t set out to curate as my practice so much as I see myself developing projects in parallel ways. I still work in ways that read as more traditional studio modes, like watercolor drawing, but people know the gallery point of view more. Putting art in the context of a show lets me champion these brilliant artists and a selection of compelling images in favor of an obvious theme. Lots of narrative precedent for development of character and mise en scène in favor of plot points.

In the essay, “Understanding the booby prize”, you state, “Thinking and talking art, even writing about it; it’s all good. But art will always be a closer cousin to food and sex: experience far outweighs the chatter”. Can you expand upon this idea?

We’ve all seen compelling things in life that defy understanding. Recent neuroscience has demonstrated that the more complex parts of our brain function in areas other than the pre-frontal cortex. That part of our brain maxes out navigating a few variables, but our subconscious can work on much greater complexity. When we expect everything to make sense we are dumbing down our toolset. Understanding happens in a sort of editing or reducing, and it actually involves distancing. All that is useful, but it is not the only useful approach.

Grilled Ceasar’s Salad, watercolor and custom scaffolding, 2014

Sex is a useful comparison. There are many reasons to think about sex, and to use analytical tools to quantify aspects of sex, but that is wholly different than an experience with having really good sex. We get caught up into a massive firing of sensual awareness when sex is really good. I think art is like that. The very best of an art experience has potential to conjure many senses and generates heightened sensitivity, even to the parts of it that are thoughts. The art triggers new thoughts rather than simply presenting a thought as this concise thing that I can understand. Understanding art is an impulse to get the right answer. Experiencing art is a dance with an image, an object that sweeps me into an entirely different frame of reference. I can find myself emotionally moved by a few works of art simply by reminding myself of seeing the work. That never happens with works that are simple to understand.

Paul Hopkin is an artist and director of Slow (Gallery) in Chicago, Illinois. Slow is located at 2153 W 21st Street, Chicago IL 60608. Currently on view at NOW: The ceiling caves in on Jason Dunda’s head and at LOO: Duty, Judith Brotman and Sandra Grauel.

For additional information, please visit Slow at: http://paul-is-slow.info/

Paul Hopkin, artist and gallery director, Chicago, IL, 2014

Interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello