Accessibility can be key in producing thought provoking images in photography. Former CPD officer and photographer Scott Fortino has navigated Chicago while making photographs with objective eye of spaces not commonly seen for the better part of 30 years. This week, the COMP Magazine traveled up to Buena Park to discuss with Fortino his early introduction to photography, time spent working on Chicago’s Police force, his fascination with modernist architecture, and his current photographic investigations with CPS Lives.

You are Chicago born and bred, grew up on the southwest side, were a Chicago police office for more than 30 years, and studied in the city with a number of important artists and photographers. I believe I first encountered your work almost 20 years ago. Can we jump back a bit and discuss any early experiences you see as important in setting you on your present course as it relates to photography?

When I was in high school, my brother was drafted and sent to Vietnam. While there, he would send home packs of Kodachrome slides. I’d come home from high school, check the mail, grab the packages, and head to the basement. This became an important ritual of my adolescent life. I would set up the slide projector on the pool table and devour the images of his life and routine there, the unfamiliar tropical foliage, the soldiers in their uniforms, and as time passed, how John and his friends aged. When he returned home, we made an informal exchange, my wardrobe for the use of his cameras. Through the viewfinders I found something familiar—a window, small, intimate, yet encompassing.

In my late 20s I became a Chicago policeman, a job that allowed me to experience the various components that make up this city’s landscape: the industrial southeast, public housing corridors, the lakefront high rises, and neighborhoods on the south and west sides. Though I had started a graduate program around that same time, I left to focus on this new career. Fast forward. I went through a series of transitions and decided to return to the grad program at UIC. Straddling these very different worlds was disorienting—the conservative culture of the department where my police colleagues gave me some hazing for going back to school, and the much more liberal, less restrictive environment in grad school. It caused me not a little bit of anxiety.

Nonetheless it was the busiest and most satisfying time of my life. I was teaching an intro class in the college, working on an ongoing commission and doing my own work, all while working full-time for the CPD. A bit about the commission: through a portfolio review I got lucky and David Travis, the now retired Curator of Photography at AIC, saw the pictures and invited me to participate in a project for the Park Hyatt Hotel. I was one of five photographers selected. These were booster pictures, positive views of the city that I could put my own spin on. The Hotel had a Richter, an elevated city view in monochrome, creamy grays and charcoal blacks; it is in the lobby. Their desire was to have photographs throughout the various spaces and rooms in a similar motif. The hotel purchased an array of pictures in various editions. I was fortunate to be able to use the labs at UIC to print this work. So, these experiences, teaching and witnessing the students discovering their own creative process and being paid for my work were extraordinarily satisfying and important in formulating my identity as an artist.

I do believe we need to revisit the photobook, Institutional, published by the Center for American Places and Columbia College Chicago in 2005. This appears to be the foundation. Can you share with us what initiated this series that found book form? Also, what were you attempting to describe about the places and the city you documented?

What the grad program made very clear was that your own experiences serve as a worthy subject for your art production. And a big part of my day-to-day routine was being a police officer. So here is where my photography became integrated with my experience as a police officer.

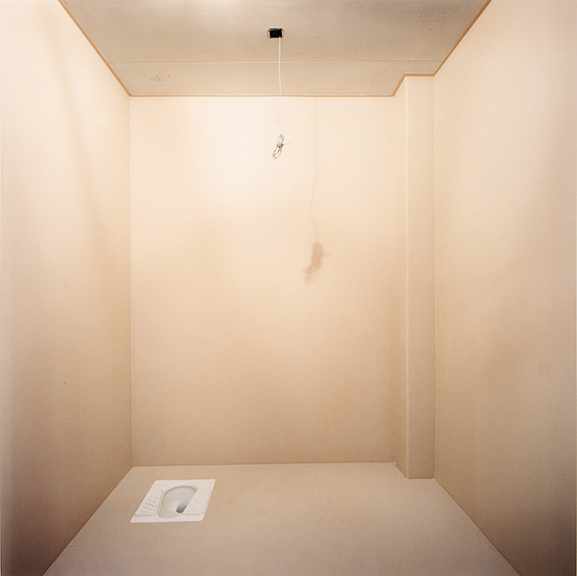

Institutional includes photographs of jails, schools, and other Chicago institutions which emerged from my time as a patrolman. For several years before I started the graduate program, I had been producing work in and around public housing projects, Robert Taylor Homes, Stateway Gardens and Cabrini Green. Even for the police, these were intimidating places, so I had to work through my own trepidation. I was somewhat familiar with Cabrini Green as it was in the police district where I was assigned. Officers could voluntarily work a day off in public housing projects; generally we chose to work Cabrini. We would walk the stairwells from the top floor checking roof access doors, inspecting each floor for lights not functioning, vacant apartments and generally being seen by the residents and assisting them in any way. Checking boxes on our inspection logs as we went along.

Institutional evolved from this type of work. It depicted the places I experienced walking into and spending time within. If I felt these places had potential for pictures I would make the necessary arrangements to come back with my camera.

My grad school advisor suggested I participate in a project set up by a resident artist at the MCA. He was involved in researching the experience of public housing for a film he was making. I was in my forties at the time, older than most students and even some instructors. I felt out of my element, but participation in this project proved to be a very valuable and foundational experience.

I produced a series of flashed snapshots of details of one particular building in Cabrini Green. This did not go over very well with my instructors when the pictures were critiqued. Over a period of two hours I was taken to task for the apparent casualness of the pictures, referred to as something akin to project tourism. One particular instructor asked me pointed questions as to what my intention was with these images. The snapshots were simply too casual for the setting, they were quick takes, not studied. I didn’t know who he was but afterward learned it was Kerry James Marshall. I had to get serious if I was going to document these places. I went back to that particular building and in a very systematic and methodical manner photographed every doorway. It was a very Becheresque typology, close quarters, in color and with flash fill light and while capturing the evidence of those who lived there. I was assisted by Tom Nowak, a studio instructor at Columbia College. At the next critique, without my knowledge, a feature writer for the Tribune had been invited. The Tribune published a selection of the doorway pictures with an accompanying article. It was a feature in the Tempo section of the paper, written by Julia Keller. I was grateful, overjoyed and exhausted.

Later a chance meeting with Bob Thall started me on the circuitous route to Institutional. Bob casually said that if a box of my pictures was on his coffee table when his publisher was visiting, well, he could take a look at my work and make his assessment. That’s how it started, while still in the grad program at UIC. After the Doors project as part of a police detail, I spent time in the schools that served the Cabrini Green community–Jenner Academy and Byrd Elementary. With principal’s permissions I began to photograph at the schools. The project spiraled out from there to include police facilities and lockups, hospital corridors and school classrooms; all emotionally charged spaces. I was attempting to describe the evidence of occupation embedded in their surfaces. The resulting images, formally precise and non-hierarchical are transformed to containers of the very human presence found in the details left behind; all done in a very straightforward and formally rigorous manner. For me this was the meat and potatoes, the very meaning of the term institutional. Some have pointed out that the spaces themselves reveal attempts to overcome their impersonal design, by brightly coloring the walls and corridors, a counterpoint to the deadening aspect of the spaces themselves.

After the publication of Institutionalyou noted that you spent time trying to find footing for new investigations. You’ve evidently found new subjects to photograph and continue working at a brisk clip with series focused upon the lake and various aspects of related to interpretations of urbanism. Lets focus on the imagery that utilizes the reflections of the glass façades of modern architecture found throughout the city. Can you discuss your process? Do you have any predetermined ideas that you attempt to adhere to?

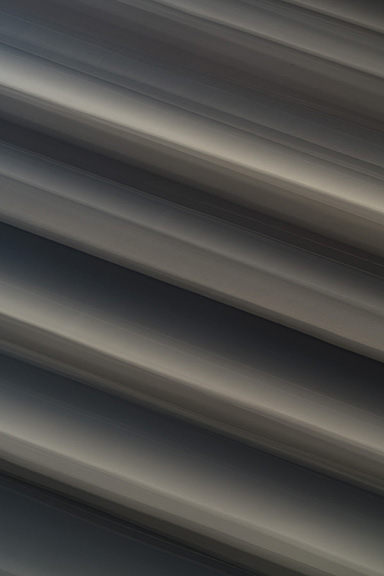

As a photographer interested in architecture and living in a city with a legacy of Miesian modernism I wanted to see what my perspective could bring to those jewel-like privileged spaces. I had no predetermined ideas other than curiosity and a willingness to take some risks.

On a cool spring morning about 5 years ago I walked the plaza between buildings at 860 Lake Shore drive and was struck by the feeling of intimacy, how the scale and proportions contributed to a sense of being in an urban room. The floor to ceiling glass of the lobbies was striking.

I understood that Mies, who had a love for trees, would move plants around in his models to capture a bit of nature into his very rigorous interior designs. What if I were to incorporate this fondness for nature into a depiction of his perfect spaces? Jesus Vassallo, Gus Wortham Assistant Professor at Rice University, put it more elegantly in his essay written for ‘A Love of the World’ an exhibit of photography he curated at the 2017 Chicago Architectural Biennial. “As Fortino directs his gaze from the public space of the city into the interiors of these buildings, the reflections caught up in the glass curtain walls virtually turn each photograph into a double exposure, a synthesis of the experience of Chicago in which the intimacy and pathos of an almost domestic interior is overlaid with an afterimage of street life and the presence of nature in the city.” That about sums it up for me.

Most recently you have been experimenting in a more formalisticvein of inquiry that I see relating to painting. You are now constructing works to be photographed. I see this as a logical progression from the multi-layered imagery seen in the Urbanism series. What prompted this investigation? How do you see this related to previous series?

Forgoing narrative content in favor of making things in the studio for the purpose of photographing is extremely liberating and a kind of terrifying leap of faith. It’s a quest to expand the boundaries in which I work, to loosen the moorings of narrative content and think about objects and color as material for photographs is an absolute visual pleasure.

Painters get this and think about that rectangle of space differently than photographers. Lens-based work is so connected to the world and its narrative content. It’s nice to take a break from that connection. To be free of those constraints and be concerned with material content and color and the labor involved in the making of the thing. It feels like something an old hippie once said about letting all his chickens run free. It’s very exhilarating! Facts become hallucinographic, space becomes illusionistic uncertain outcomes are the norm. in the studio, I can make something and then make a picture of it. And it can be about color and light and space and texture and movement and time. And that is the narrative. And that might be enough.

This question is a bit of a deviation, but I am wondering if you see your long relationship with the Chicago Police Department having any impact on your photography practice. If so, how? If not, why?

It wasn’t until Institutional was put together in book form that I fully realized my work will be forever tied to the day-to-day routine of my job as a police officer. Previously I believed that my art and what I did for a living existed on separate planes and the twain would never meet. Pulling together the images for the book led to the revelation that the observational and task-oriented police experience is similar in nature to that of the photographer who looks closely at the environment in a methodical and systematic way. This has helped me to come to terms with my career as a police officer, for which I have been quite conflicted, and to appreciate how it opened my perception and deepened my appreciation of the urban fabric that surrounds and envelops me.

What do you value most in your photography practice?

Photographers spend a great deal of time editing images, with digital technology it can be done at a much more rapid pace. Your attention is sharpened and relaxed simultaneously in a state of recognition and acquiescence. Seeing the work as a page you can scroll, one can discern the direction of the whole, details and variations within the work as it proceeds. It’s like contact sheet 5.0.

You are now working with Suzette Bross on the CPS Lives project. We looked at a couple images you made at the Walt Disney Magnet School. You are now looking at making images at schools on the far south and West sides. Do you have any specific goals or intent you hope to contribute to this expansive and important project? In addition to this what other plans do you have for 2019?

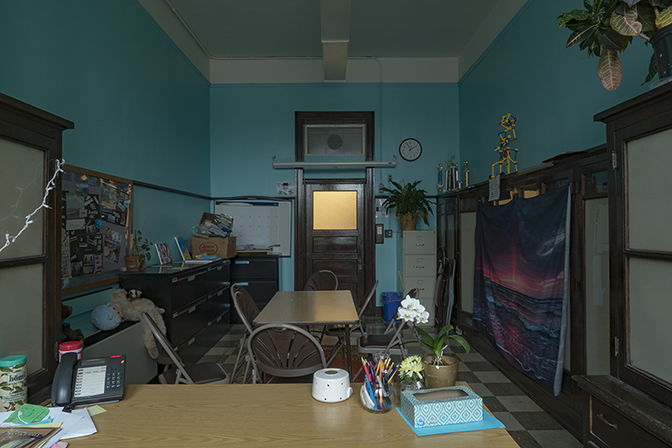

I feel very fortunate to be part of the CPS Lives project by contributing a selection of architectural interiors to the larger and more expansive narrative of Chicago Public Schools.

I have always been drawn to educational spaces; it’s all about where discovery happens. Where the first signs of recognition take place, of who we are and the beginning of understanding the world and our place within it; emotionally-charged spaces where students are challenged to formulate their own identities.

Now, walking through these corridors, familiar yet unknown, getting disoriented and slightly lost, I hope to find my way forward, with empathy and compassion to a narrative of restoration. While devoid of people, these classrooms, hallways and common areas become stage-like scenarios of anticipation for what is about to happen or the aftermath of what recently did. Time slows, we can take in the details, the arrangement of objects, the room’s color scheme, the quality of the light. In the resulting pictures, though formally precise and non-hierarchical, the spaces become containers of the very human presence found in the details left behind.

Ultimately, through these pictures, I hope to restore something to the current CPS narrative whether that is a form of joy, compassion or playfulness. For me this is a personal archeology, moving through the quotidian material reality of our institutional spaces to uncover evidence of our fragile humanity contained within.

For additional information on the photographic practice of Scott Fortino, please visit:

Scott Fortino – http://scottfortino.com

Museum of Contemporary Photography – http://www.mocp.org/collection/mpp/fortino_scott.phphttp://www.mocp.org/collection/mpp/fortino_scott.php

Document – http://documentspace.com/exhibitions/scott-fortino/

WBEZ 91.5 Chicago – https://www.wbez.org/shows/eight-fortyeight/institutional/e9097b20-3e6e-42fd-a505-c34f50c418d5

CPS Lives – https://cpslives.org/home

Photographer interview and portrait by Chester Alamo-Costello